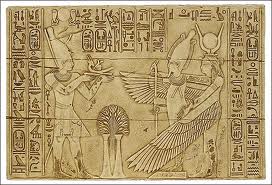

V. Osiris, Isis and Horus

Horus, Osiris and Isis

A preliminary bibliographical note

We have reached a happy moment in the Egyptology of the gods. The great scholars of the past (mostly German, French and British) have had their say, bequeathing us a virtual library of archaeology, decipherment and explication. Theories about the nature of the gods have been proposed, elaborated and adopted or dismissed. Ambition has been chastened and unsupportable ideas chastised. Along comes another generation of consummate scholars, German, Dutch, American, Egyptian: the groundbreaking Erik Hornung (whose Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt sets out a new orthodoxy regarding all questions); the wide-ranging Jan Assmann (whose Mind of Egypt in particular places the gods in relation to all the history, culture and civilization of Egypt); Ian Shaw, who has assembled essays by other learned historians to produce for Oxford an intelligent, dry but readable, account (the History of Ancient Egypt, which places the gods in their various contexts) and, with Paul Nicholson, a reader’s companion (The British Museum Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, which gives scholarly but enlivening definitions).

Erik Hornung

In addition to these we have Lucia Gahlin for the general reader (see again her Egypt: Gods Myths and Religion) and the graceful but profoundly summative work of Geraldine Pinch, whose full descriptive title I cite here: Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses and Traditions of Ancient Egypt). To the books on the gods I might add a recent study of the Pharaohs, brief and accessible (Peter A. Clayton’s Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt) but withal comprehensive enough, as supplemented by Hornung’s and Pinch’s general introductions, by Shaw’s comments (in his Oxford History) and, with Nicholson, by their dictionary entries, to give us help with the question of the pharaoh’s divinity. On the Internet I have found information on the Cults and their Locations. As for the Temples and Tombs, an enormous subject, though Wilkinson (The Complete Temples and, with Reeves, The Complete Valley of the Kings) might have served, I will instead excerpt passages from Kent R. Weeks (his and his colleagues’ Valley of the Kings).

It is especially appropriate as we turn to the myth of Osiris that we be eclectic. (In what follows I will quote the scholars mentioned above, citing them by their last names only and putting their words in quotation marks, often without attribution, to distinguish theirs from mine; in lieu of a scholarly apparatus I intend a pastiche useful to the curious.) Osiris himself is eclectic and the longest lived of all Egyptian gods, along with Isis even exceeding for a few centuries the temporal and geographical boundaries of ancient Egypt. Osiris and Isis are, as well as being brother and sister, man and wife, similar in their bewildering diversity, so different from one another en masse as almost not to belong together in the same story. Likewise Horus, their son, and to some degree Seth, the brother of Osiris and Isis. Nepthys, their other sibling, is by contrast a relatively uncomplicated figure. In one sense the story of Osiris and his family is simple, certainly the genealogy. He was “the eldest son of the earth god Geb and the sky goddess Nut” (Pinch). “He and his sister-consort, Isis, ruled Egypt together,” until Seth came along.

Osiris

“Osiris died and became ‘the Inert One’” (cp. Amun). “The gods eventually decreed that he should be resurrected as the king and the judge of the dead and that his posthumous son Horus should be made king of the living.” There is much history that Pinch subliminally summarizes here. Assmann is more explicit: “With the so-called ‘democratization of the afterlife’ that took place during the First Intermediate Period (2494-2345) the dead king was identified with Osiris, while the living ruler was equated with his son Horus. But it appears to have become possible for any deceased person to be resurrected in the person of Osiris.” As Wilkinson succinctly notes, Osiris “figures prominently in both monarchical ideology and popular religion,” “as a god of death, resurrection and fertility,” he adds. As for history: Assmann speaks of “The Egyptian ritual of historical renewal” and of geography both local and general. For each Egyptian temple,” he notes, was “a cosmos in its own right,” “each represented the totality of Egypt.” Osiris stands for one part of Egypt, Seth for the other. Isis in restoring Osiris, restores Egyptian unity.

Assmann sees in the myth of Osiris’ dismemberment and the “reconstitution of the 42 severed parts” “a response to Persian, Greek and Roman unification in the Ptolemaic period.” He also regards it as a reflection of the unity of the Ogdoad and the unity of the Ennead. Shaw and Nicholson see in his combined fertility and funerary aspects the “natural transformation” of Osiris “into the quintessential god of resurrection.” According to Wilkinson, “Osiris was originally a fertility god with chthonic connections based in his identification with the earth, and he was associated at some point with the Nile’s inundation, perhaps through its resultant alluvium and fertility.” His body is represented as either white (the color of the mummy’s bindings), black (the color of the rich alluvium) or green (the color of the new vegetation). “As time progressed, as his cult spread throughout Egypt,” Wilkinson says, “the god assimilated many other deities and rapidly assumed their attributes and characteristics.” “His name, wennefer, probably means something like ‘he who is in everlastingly good condition.’”

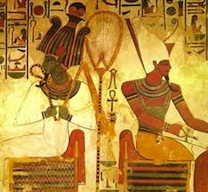

Osiris and Seth

In other words, Osiris was a god of immortality, one of the few Egyptian deities who died and the only to be reborn. “An important development, however,” Wilkinson adds, “which went beyond his basic identity as a resurrected god and ruler of the underworld, was the role that he played as judge of the dead.” Early on Osiris is represented as being judged; by the end of his 2000-year rule, he is the Judge. Osiris is a comprehensive god, the result of his assimilation of various functions. “The Osirid legends thus incorporate Osiris’ ‘siblings’ Isis, Nephyths and Seth as well as his son Horus,” all whom equally represent allegorical, mythic, historical and political values, and with them constitute “the most extensive mythic cycle in ancient Egyptian culture.” The political theme was first spelled out by Plutarch (in De Iside et Osiride): “The god once ruled Egypt,” in Wilkinson’s summary, “as a king, until he was murdered and cruelly dismembered and scattered by his jealous brother Seth. Due to the loyalty and dedication of his wife Isis . . . Osiris was found and revivified and became the god of the netherworld.”

Let us briefly interrupt our commentators and attend to a simpler, more coherent telling of the tale, by the lecturer Lucia Gahlin: “During a time beset by turmoil, the birth of the god Osiris was heralded by an array of good omens and signs. Before his appearance, war and cannibalism appear to have been the order of the day — the people were said to be barbarians. Osiris became king of the Delta town Busiris, but it was not long before he was made king of all Egypt. His skill was in teaching how to farm and to lead law-abiding lives and worship the gods. When Osiris had restored order to the country, he went on a journey. His wicked brother Seth seized the opportunity to gather together 72 conspirators. They hatched a plot. On Osiris’ return they threw a party. Following an enormous banquet, Seth suggested that the revelers should play a game (devised by himself of course). A chest was laid out in the great hall and the game was to see who could fit inside it. When Osiris’ turn came, he climbed into the chest and — not surprisingly — it was the perfect-sized coffin for him. A conspirator slammed the lid shut.

Isis

“Osiris died and thus became ruler of the dead in the Afterlife. This, however, is by no means the end of the myth, because Osiris’ dead body, still inside the chest, was disposed of in the Tanitic branch of the Nile. Its journey had just begun, for instead of sinking to the murky depths, as Seth had hoped, it floated with the current northwards towards the coast, and then out into the Mediterranean Sea. Proceeding to bob all the way to the busy Lebanese port of Byblos, it finally came to rest in the entangled roots of a tree. Engulfed by the tree, the chest became part of its trunk, later a pillar in a temple. Meanwhile, Osiris’s sister and consort Isis had set her heart on retrieving the body of her husband. . . . Isis followed a tip-off to Byblos, where she gained access to the tree-pillar by turning herself into a swallow and performing rituals to make the dead Osiris immortal. . . . Once in possession of the chest, she returned with it to Egypt and hid it in the marshy Delta while she went to collect her son. During her absence, Seth happened by and cut Osiris’s body into fourteen pieces. Isis then began her laborious search for the pieces . . . .”

The genius of this telling is that it masquerades as a human tale all the while that it speaks the most mythic and disguises the most literal, historical meanings. To revert to Wilkinson’s interpretive account of the story’s continuation: “Horus, the posthumously conceived son of Osiris and Isis, avenged his father’s death by defeating Seth and in time became the king of all Egypt as the rightful heir of Osiris.” Thus the myth legitimizes male succession in Egypt, which bore matrilineal traces. “This story had great appeal both as a theological rationale for the Egyptian monarchial system in which the deceased king was elevated with Osiris and was followed to the throne by his ‘Horus’ successor, and also as a story that proffered the hope of immortality through resurrection — which had a universal appeal and was claimed at first by kings and eventually by nobles and commoners also.” Thus the myth reinforces the claims of immortality on behalf of both the king and the individual soul. Unlike most other gods, Osiris is seen as benevolent, “a benign deity who represented the clearest idea of physical salvation.”

On the so-called “human” level (or even the level of mythic narration), the relationship between Osiris and Isis could hardly be more intimate: brother and sister, husband and wife. Before Maria, Isis is the most tangible symbol of motherly sympathy, before Christ, Osiris the most plangent example of death and rebirth. In other words, the two figures reinforce one another and bind themselves into a dyad. On the allegorical, political and historical levels, however, they diverge at almost every point of contact. According to Pinch, Isis “was most commonly shown as a woman wearing the throne symbol that helps to write her name. As the ‘throne goddess,’ she was the mother of each Egyptian king.” Thus her universal role as mother creates a tension with her nurturing role for any single king and overrides her sisterly and wifely relationships with Osiris. “Her maternal tenderness eventually included all humanity.” Like Maria, she transcends the family and history. Moreover, she is a late-comer to the Osiris story.” “It is not clear whether Isis featured in the earliest myths about Osiris and Horus.”

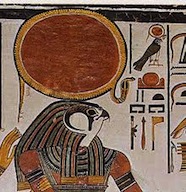

Horus

One way of figuring her single status, like that of Maria, is to call her the Virgin. Another is to see her as self-propagating. “Like the creator deity Atum,” according to Pinch, “she is able to produce life without an active partner.” She does not require Osiris. She is also magical, which sets her apart from many female divinities. When Horus cuts his mother’s head off, the gods give her a new head, “sometimes,” according to Pinch, “that of a cow.” There is a myth that when the Divine Tribunal finally made Horus king, he repaid his mother by raping her. Domestically, this would put Osiris in an awkward position. Pinch explains the motif by saying that “each king had to take possession of the throne goddess and beget a repeat of himself.” Unlike Osiris, she is truly metamorphic: “She could be shown as a cobra suckling kings.” “In ‘The Contendings of Horus and Seth’ she transforms herself into an old woman to fool the divine ferryman and into a young girl to trick Seth into making damaging admissions. She is able to turn the sun god’s own power against him to get what she wants.” Isis is sometimes represented as goddess of the sea.

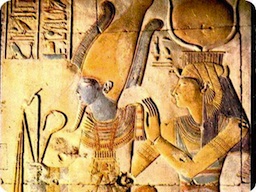

Osiris and Isis

Her different identities and mythic functions make it difficult to align her with Osiris, in fact impossible to do so consistently. Unlike him, in The New Kingdom she is a creation goddess and a form of “all goddesses, who became merely the ‘names’ of Isis.” Osiris is likewise multifarious. “It has been claimed,” says Pinch, “that Osiris was originally a deified Predynastic king, a primitive vegetation spirit, a jackal god of the royal necropolis, or a mother goddess.” Like Isis, he gradually takes over the attributes of other deities, such as the funerary god Andjety at Busiris and Khentamentiu at Abydos.” He was born wearing a crown and was chosen to succeed his father Geb, by the sun god himself.” Thus Osiris and Isis compete with one another for a special “solar” status. As for their sexual relations, Osiris’s potency seems almost to increase after death, for only then does he make Isis pregnant. Whereas Isis rules in this world, Osiris rules in the underworld. His body, as we have seen, at Byblos was regenerated within a tree, thus giving him Druidical powers that Isis lacks. Finally, he is a just judge and savior.

Since Osiris and Isis compose not merely a dyad but also, with Horus, a triad, we must give some attention to Horus, who completes this nuclear family but also transcends it. Horus is many different gods in different periods. According to Pinch, he begins as a sky god. (“The Egyptian word her from which the god’s name is derived means ‘the one on high,’ in reference to the soaring flight of the hunting falcon, if not a reference to the solar aspect of the god”). He then becomes a sun god. (“As Behdety or ‘he of the behdef,’ Horus was the hawk-winged sun disc that seems to incorporate the idea of the passage of the sun through the sky.”) His form can also be leonine (“By New Kingdom times, the Great Sphinx, originally a representation of the 4th Dynasty king Khafre, was interpreted as an image of Hor-em-akhet”). He is a god of kingship. “As the hawk-winged Behdety, Horus became one of the most widespread images in Egyptian art and rivaled the fame of his mother Isis and his father Osiris.” “In southern Egypt he enjoyed the attentions of his own cult along with his consort Hathor and their son Harsomptus.”

Horus as child

Unlike Isis and Osiris, he is known not only as a powerful deity in his own right but also as a charming child. A parallel may be drawn between Aphrodite (Isis), Hermes (Osiris) and Eros (Horus). Each, we note, is an intensification of other gods, which perhaps explains their volatility and fame. As a child, Horus is innocent (cp. Isis’s beauty and Osiris’s immortality as their leading charismatic attributes). In this avatar, the older hawkish sky god is subordinated to the later anthropomorphic Osiris. “Harsiese, ‘Horus-son-of-Isis,’ and Harpokrates, ‘Horus-the-child,’ become separate forms for the youthful Horus whom Isis has borne and reared,” says Hornung. “There is no other Egyptian narrative of the birth, growth and youth of a deity that is as extensive or dwells with such delight on concrete details.” Like the infant Hercules, “Horus is represented as a child,” say Shaw and Nicholson, “with the power to overcome harmful forces.” They illustrate the point with a sculpture of Horus the child standing atop a crocodile beneath the head of the benevolent god Bes. At the other end of the scale, Horus is cosmological.

Hornung: “Apart from the goddesses who ‘bore’ other specific deities in myth, there is the idea of a ‘mother of the gods’ who bears all the gods. In the New Kingdom and late period the sky goddess Nut, who bore the sun and the moon,’ often has the epithet ‘she who bore the gods.’ This epithet refers to the heavenly bodies, whom the sky goddess daily ‘bears’ and again ‘swallows’— an idea that leads to the depiction of Nut as a sow.” Isis, the mother of Horus, is called “the mother of the god,” elsewhere, in the New Kingdom, “the mother of all gods. . . . Corresponding to the idea of a universal ‘mother of the gods’ is that of a ‘father of the gods,’ to whom all other deities owe their origin. At first Amun and a little later other gods such as Ptah and Horus acquire an epithet, which seems to have been coined in the New Kingdom, ‘father of the fathers of all gods.’” Horus, then, is a primitive creator, the lord of the sky, the son of Isis, a god of order dispelling chaos. He is the god who, from the moment of his conception, was destined to be king. As the devoted son of Osiris “he is also the prototype of all priests.”