VI. Cascading Triads

The three Giza pyramids

Groups of seven gods (the hebdomads), groups of six (the hexads), groups of five (the pentads) are not unknown to ancient Egypt (we will take up the ogdoads, the groups of eight, and the enneads, the groups of nine, presently). Erik Hornung, in his Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many, says, in commenting on the standard triads, “Beside tripartite forms such as Ptah-Sokar-Osiris there are quadripartite forms such as Amun-Re-Harakhte-Atum or Hamarchis-Khepry-Re-Atum,” adding that “the Egyptians place the tensions and contradictions of the world beside one another and then live with them. Amun-Re,” he goes on to explain, “is not the synthesis of Amun and Re but a new form that exists along with the two older gods.” The Egyptian gods are in many ways multiple, as opposed to singular.

In the New Kingdom Hornung finds “a trinity, or tri-unity — not of God but of the gods and their cult places. The classical formulation of this specifically Egyptian trinity,” he says, “was achieved at the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty in the Leiden hymn to Atum: ‘All gods are three: Amun, Re, Ptah; they have no equal; his name is hidden as Atum, he is perceived as Re [literally, he is Re before men], and his body is Ptah. Their cities on earth remain forever: Thebes, Heliopolis and Memphis, for all time.’ This trinity of Amun / Re / Ptah is also found elsewhere; its earliest attestation is not Ramessid, as Eberhard Otto states, but dates to the Pharaoh Tutankhamun (1347-1338 B.C.), the successor to Akhenaten.” “One could argue,” says Hornung again, “for an ‘equalization’ required by Egypt’s religious politics.”

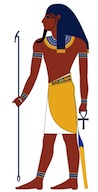

Khepry

Re-Harakhte

Atum

“But what could be the purpose of ‘equalizing’ Horus and Sothis or Hamarchis, Khepry, Re and Atum? In the last example the three daily forms of the sun god are evidently present together in the Great Sphinx (Hamarchis): the sun is Khepry in the morning, Re or Harakhte in the middle of the day, and Atum in the evening. Thus the Sphinx is the sun god, and his three forms.” The Egyptian gods are not, however, like the Biblical divisions of the Godhead, arranged in theological trinities. Hornung is also quite adamant in making the case against arguments for an ancient Egyptian “monotheism.” “It is clear,” he says, “that syncretism does not contain any ‘monotheistic tendency’ but rather forms a strong counter-current to ‘monotheism’ — so long as it is kept within bounds. Syncretism softens henotheism” in the Egyptian system.

To distinguish between the Greeks and the Egyptians he writes, “We shall find repeatedly that Egyptian deities do not present themselves to us with as clear and well defined a nature as that of the gods of Greece. The conception of god which we encounter here is [instead] fluid, unfinished, changeable. But we should not impute to the Egyptians confused conceptions of their own gods; such an idea is contradicted by numerous specific details.” Henotheism, the ability to move from one god to another or to emphasize one avatar of a single god after another, does “concentrate worship upon a single god” (and so prevents Egyptian religion from devolving into mere polytheism or pantheism), but it also “stops it from turning into monotheism, for syncretism means that a single god is not isolated from all the others.”

David P. Silverman (“Divinity and Deities in Ancient Egypt,” in Byron E. Shafer, ed., Religion in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Myths and Personal Practice) complements Hornung:

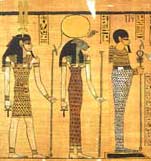

Nefertem, Sekhmet and Ptah

“Egyptians envisioned their divinities in small groups. They could be paired, as they were in some regional cosmogonies. More often they belonged to family groupings, which consisted of father, mother and child. At Abydos it was Osiris, Isis and Horus. At Thebes the sacred triad was Amun, Mut and Khonsu; at Memphis, Ptah, Sekmet and Neterem. Such groupings, extremely common, often linked gods and goddesses from different precincts and with varying significance. Hathor of Dendera, for example, was linked to Horus of Edfu. The temple at Edfu was dedicated to Horus and only he was in residence. Horus was often portrayed with his consort, Hathor of Dendera. She, however, together with her sons Ihy and Horus-Sematawy, was in residence at the new temple dedicated to her at Dendera.”

Silverman here is contravening the earlier view of Egyptologists that only local gods were worshiped in specific locales, one evidence of so-called “henotheism”; in other words, henotheism was tempered by a flexibility that enabled gods to move from one region to another and by the prevalence of certain “universal” gods. Even the primeval deities, according to Hornung, who express the chaotic world before creation, “are conceived of as a triad: Nun, ‘the weary’ or ‘inert,’ primeval flood, Huh, ‘endlessness,’ Kuk, ‘darkness.’ Atum, the earliest creator god for whom we have evidence, has a self-explanatory name which is more difficult to interpret. It can mean ‘not to be’ or ‘to be complete.’” “Khnum, Anukis and Satis,” Hornung adds, “represent a nonce triad. Khnum is the local god of Elephantine.

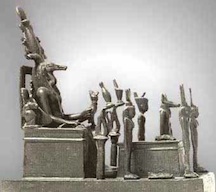

Anukis, Satis and Khnum

“Here the goddesses Anukis and Satis were worshiped along with him.” These triads were not conceived as theological trinities till much later. “When after the Amarna period,” says Hornung, “the tri-unity of god is postulated for the first time in the Leiden hymn to Amun, the text does not say ‘god reveals himself in three forms’; [instead] the plural form is used: ‘All gods are three. Amun, Re and Ptah. His name is hidden as Amun, he is perceived as Re, his body is Ptah,’ a plural that is taken up again by a singular suffix [my emphases]. Anthes interprets Amun’s name as ‘he who is an entirety,’ Bonnet as ‘he who is not yet complete’; Kees as ‘he who is not yet present.’ I myself,” says Hornung, “believe that ‘the undifferentiated one’ is a more apt rendering, because it includes both aspects [of his existence].”

Elsewhere Hornung shows how the triads emerged. “When a child [was] added to a divine couple, the result [was] a triad, the preferred and most frequently encountered grouping of Egyptian deities. . . . But we should follow Eberhard Otto in assuming that the idiom of kinship in which triads are presented is secondary in comparison with the important symbolism of the number three. ‘Three’ is the simplest and hence the preferred way of expressing ‘many’ or the plural, which is indicated in the Egyptian script by three strokes or by writing signs three times; some texts equate ‘three’ quite explicitly with the plural. The existence of a large number of deities and the preferred articulation of them into triads comes quite late.” Hornung also helps us understand the emergence of the ogdoad and the ennead:

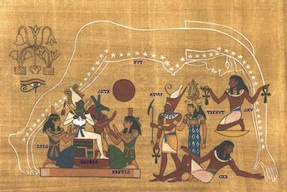

The Ogdoad

“The succeeding period, the Ramessid, brings a true renaissance of Amun as king of the gods, while the god Seth is added as a fourth to the triad Amun, Re, Ptah, although the triad survives as well. . . . ‘Four’ occurs doubled as the ogdoad of Hermopolis, and the name ‘eight-city’ was given to their cult center, Hermopolis, as early as the Old Kingdom. Thus the ogdoad and related ideas about creation may be posited for the central Old Kingdom even though the names of the four pairs of primeval deities are not attested until the late period. The names themselves vary but always add up to eight, or rather to four couples of gods/goddesses. The most important classificatory scheme is the ennead.” Though the ogdoad, then, dominated the early Egyptian periods, the ennead arose to complete the pantheon.

The Ennead

“It too is an intensified form of the plural (three times three) and is first attested in the ennead of Heliopolis, which served as the model for further enneads in the pantheon; a complete listing of the nine gods occurs as early as the Pyramid Texts . . . Nor is the number of members of the ‘ennead’ canonically fixed at nine, even though the genealogy usually ends with Osiris and Isis, and because of that number omits their son Horus. . . . The later enneads, which were devised throughout the country on the model of the ennead of Heliopolis, sometimes have only seven members, as at Abydos, but in other cases fifteen, as at Thebes.” “The ranking of cult places automatically results in a hierarchy of their deities.” The reader may study illustrations of the Egyptian gods and further apply these observations to them.

Another note on the animal form of the ancient Egyptian gods

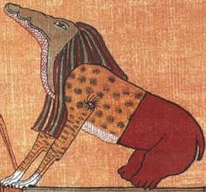

Ammit

In section IV ("Amun") I had quoted the great French Egyptologist, Henri Frankfort, on why the Egyptians give to their gods animal forms. The matter is more complicated than I had (deliberately) represented it. Let us begin with Hornung's paraphrases of Frankfort on similar questions: “Henri Frankfort proposed much more aptly [than those who suggest that the theriomorphic form of Egyptian gods are ‘pictures of them’] that they should be taken as ‘ideograms’ or as pictorial signs that convey meaning in a metalanguage.

“The gods may indeed inhabit their representations as they may inhabit any image, but their true form is ‘hidden’ and ‘mysterious,’ as Egyptian texts emphasize.” “Hathor and her iconography appear still richer when one recalls that she is also imagined as a lioness, a snake, a hippopotamus, and a tree nymph. Although the various forms are not equally old, we are not observing a historical development in which one form replaced another; at all periods different ways of depicting the goddess simply existed side by side.

“Men of the period c. 3000 B.C. felt themselves defenseless without an animal disguise. Animals appeared to be the most powerful and efficacious beings, far superior to men in all [sic] their capacities. This probably explains why in late predynastic times the powers that determine the course of events were mostly conceived in animal form. . . . By 2800 B.C. animal names for the gods at last disappeared for good. The extraordinary evolution from ‘dynamism to personalism’ (Bertholet) occurred between 3000 and 2800 B.C. . . .”