VII. The Dyads and Individual Gods

It has become a cliché to speak of the double nature of Egypt or at least of the double view of all things held by ancient Egyptians: heaven and earth, upper and lower Egypt, day and night, male and female. The representation of two gods, such as Nut and Shu, as a dyad is perhaps related to this propensity, as is the embodiment of an ambiguity within the One God, such as Amun. According to Hornung, the original dyad is the existent and the non-existent. Moreover, “the greatest totality conceivable is ‘the existent and the nonexistent,’ and in these dualistic terms the divine is evidently both one and many,” the subtitle and principal thesis of his study of ancient Egyptian religion. “God,” he observes, “is a unity in worship and revelation and is multiple in nature and manifestation. Truth values are not mutually exclusive.”

Thus, “for the Egyptian, being and nothingness are identical. The phenomenon of death is a concomitant of creation. Primeval flood and darkness constitute the pre-creation. For the Egyptian the entire extent of the existent, both in space and in time, is embedded in the limited expanses of the nonexistent. The nonexistent does not even stop short at the boundaries of the existent but penetrates all creation. No wonder we encounter the nonexistent everywhere.” It is a fetchingly sophisticated philosophy (for a “non-philosophical culture”), one sympathetic to our modern sensibility. “There is also the other side of nonexistence, its potential for fertility, renewal and rejuvenation. Anything that exists becomes exhausted and needs regeneration, which can be achieved only through the temporary removal and negation of existence.”

Thus what some see as the ancient Egyptian obsession with death, as expressed in its funerary culture, is viewed by Hornung positively. “This necessity [for regeneration]” becomes the basis for “the positive, indeed absolutely essential, significance of what the Egyptians call the nonexistent, which is anything but negative. Death is the gateway to enhanced life in the next world,” which explains the brio with which the passage to the next world is celebrated and the philosophical insouciance with which it is contemplated. “Egyptians remain detached and balanced, and avoid falling into any nihilism or abrogating the self by surrendering to an unlimited state of nonexistence in which everything is possible; both these attitudes would constitute a devaluation of the existent and a fixation with the nonexistent.”

“The Egyptians never succumbed to the temptation to live in the transcendence of the existent release from imperfection, from dissolution of the self, or from immersion in and union with the universe.” As well as the duality of the universe the Egyptian gods for Hornung also express its diversity. “The limits to the gods’ nature in time, space, power and knowledge are part of the more general phenomenon,” he says, “of their diversity. This fundamental characteristic of everything that exists, this diversity — renders it impossible to credit the gods with absolute qualities or absolute existence. The large number of the gods is itself an aspect of their diversity. The essence of the primeval god is that at first he is one and then, with creation's diversity, many.” It has been estimated that there were 2000 ancient Egyptian gods.

“‘Millions’ — enormous and unfathomable but not infinite multiplicity — are the reality of . . . creation, of all that exists.” The 2000 gods likewise represent an enormous and unfathomable but not infinite multiplicity. Likewise the multiplicity of the One God. The Graeco-Roman period applies new formulations of the old epithet to Amun: “He is ‘a million millions in his name,’ and the city Thebes can be called the ‘container of a million,’ that is, the vessel of the richly diverse Amun.” There is also the difference of sex, which distinguishes the Egyptian, say, from the monotheistic religions of Israel and Islam. Here again the dyad figures; but also the creator is often seen as androgynous, not a feature of most other western religions. For Hornung “The nude but sexless colossi from Karnak are evidence” too of this ambiguity.

Nekhbet and Wadjet

On a less theoretical plane, Gahlin lists for us the most prominent dyads: Geb, the Earth god and Nut, the goddess of Heaven; Horus and Seth, two brothers who are sometimes allegorized as Good and Evil, Order and Chaos; Isis and Osiris, originally paired without their offspring Horus; the fecundating Shu and Tefnut; Wadjet and Nekhbet (cobra and vulture). Wilkinson extends the list and offers useful generalizations: “Egyptian thought usually stressed the complementary nature [of the two gods] as a way of expressing the essential unity of existence.” “The endless duality found throughout the cosmic, geographic and temporal aspects of the universe is found in pairs of gods and goddesses, which represented the binary aspect of the world.” “Some gods,” he notes, “were created as counterparts to established gods and goddesses.”

“Almost invariably,” he continues, “dyads are composed of male and female elements,” paired as lovers, or man and wife, “though there are a few examples of sibling dyads of the same sex such as the brothers Horus and Seth and the sisters Isis and Nephthys. Sometimes too, deities may be mentioned together in pairs when their roles or areas of influence are clearly related.” This adumbrates the more modern allegorical traditions that manifest in Greece, Rome and Renaissance Europe. “Another way in which Egyptian religion formed groups of two deities is when two gods are utilized to represent a larger group. This may be seen in the examples of Thoth and Horus, who are sometimes depicted together as representing the four gods of ritual lustration, Horus, Seth, Thoth and Nemty.” The dyad is not always exclusive.

At an even more empirical or practical level Shaw and Nicholson, in their Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, list under dyads “pairs of statues, often carved from the same block of material, either representing a man and his wife or depicting two versions of the same person, the former a common, the latter not a common, practice in other civilizations. “There are also occasional groups of two identical funerary statues portraying a single individual; the intention, it has been suggested, of such ‘pseudo-groups’ may have been to represent the body and the spiritual manifestations of the deceased.” They add: “It is possible that royal dyads, such as the granite double statue of Amenemhat III from Tanis may portray both the mortal and deified aspect of the pharaoh.” We note that these examples too reflect a philosophical disposition.

*

Hornung: “The ‘anthropomorphization of powers’ produced the first gods in human form, but other methods of depicting this phenomenon appear at the same time. The cow heads that crown the Narmer palette contain a human face; the ‘land of papyrus’ has a human head, and so on. . . . During the first two dynasties the group of purely anthropomorphic deities appears in addition to the gods in purely animal form, who are still predominant. . . . What is lacking at the beginning of the early dynastic period is the ‘mixed form’ of gods, combining human and animal elements, which is so characteristic of Egypt. Toward the end of the Second Dynasty the first gods in human form with animal heads appear on cylinder seal impressions.”

“In the iconography of other religions we find many ways of linking a deity pictorially with an attribute. The Greeks and Romans tended to put the attribute in the deity’s hand, while the Hittites placed deities on animals that relate to their nature and manifestation — a tradition that can be traced back through the decoration of seals of the Akkad dynasty to the beginnings of Sumerian civilization. Mesopotamian deities can have a human head that sits on an animal body. In all these cultures the gods appear in the human form after the anthropomorphization of the powers. But none of these animals, plants and objects related to the manifestation of deities offers any information about the true form of the ancient Egyptian deity.”

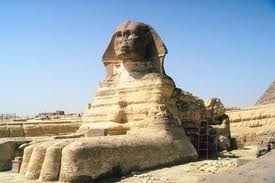

The Great Sphinx

“A combination of a human body with an attribute for head may be Egyptian, but it is not the only alternative and should not be equated with the Egyptian image of gods. The opposite solution, elaborated more thoroughly in Mesopotamia, is best known from the Egyptian sphinx; here the animal body is crowned with a human head, which may in extreme cases have the ears and mane of the animal, so that only the face remains human. . . . Whatever combination the Egyptians chose, the mixed form of their gods is nothing other than a hieroglyph, a way of ‘writing’ not the name but the nature and function of the deity in question. [I]t is quite in keeping with their views to see images of the gods as signs in a metalanguage.”

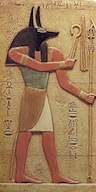

Anubis

"Every image can constitute a powerful but, in the last analysis, limited and imperfect expression of the nature of the deity. This imperfection is the root of the multiple forms of Egyptian gods, which is analogous to the multiplicity of their names. It often renders their iconography difficult and confusing. The canine Anubis and the mixed crocodile, lion and hippopotamus of Theoris are relatively fixed, but the rest of the major deities are true to their common epithet ‘rich in manifestations’ and behave, to quote another epithet, as ‘lord of manifestations’; the word ‘lord’ here means that they have power over something. The greater the god, the more attributes; the greatest, Re, has the most associations.”

Finally Hornung says: “Monotheism does not arise within polytheism by way of a slow accumulation of ‘monotheistic tendencies’ but requires instead a complete transformation through patterns. Tendencies to classify the pantheon should not be equated with an inclination toward the development of monotheism.” Was the ancient Egyptian view of reality less, or more, sophisticated than ours? It may take modern man some time to realize that the ancient conception of the universe was more nuanced and comprehensive than the modern conception.

Note: The individual gods are best referenced in Wilkinson’s Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt (London: Thames & Hudson, 2003) or by Googling their names.