Quoted from

- Charles A. Moore, Ed. The Japanese Mind: Essentials of Japanese Philosophy and Culture, whose first edition appeared in 1967. This collection includes essays by Miyamoto Shoson, Sakamaki Shunzo, Hanayama Shinsho, Yukawa Hideki, Suzuki Daisetz Teitaro, Kishimoto Hideo, Nakamura Haime, Ueda Yoshifumi, Hori Ichiro, Furukawa Tesshi, Kosaka Masaaki and Kawashima Takeyoshi

- Herman Ooms, Tokugawa Ideology: Early Constructs, 1570-1680

Confucianism and other doctrines in Japanese cultural history

A.

Prince Shotoku found in Buddhism a universal basis for the relationship of the ruler and the ruled but also utilized the Confucian idea of Heaven, Earth and man to establish the central authority of the court. “When you receive the imperial commands, fail not scrupulously to obey them; the lord is Heaven, the vassal is Earth. Heaven overspreads and Earth upbears. When this is so the four seasons follow their due course, and the powers of nature obtain their efficacy.”

Prince Shotoku (574-622) emphasized harmony or concord in human relations: “Above all else esteem concord, make it your first duty to avoid discord. People are prone to form partisanships, for few persons are really enlightened. Hence, there are those who do not obey their lords and parents, and who come in conflict with their neighbors. But, when those above are harmonious, and those below are friendly, there is concord in the discussion of affairs.”

Some scholars say that this conception of concord (wa) was adopted from Confucianism, for the word “wa” was used in connection with propriety or decorum in that work; concord, however, was not under discussion. Shotoku, on the other hand, does advocate concord as a principle of behavior. His attitude seems to have been derived from the Buddhist concept of benevolence, or compassion, which should be distinguished from the Confucian concept.

Kitabatake Chikafusa (1293-1354) advocated the Shintoist idea that the Sun Goddess provided the basis for the nation. Confucianism, though, provided the best theoretical basis for a theory of nationalism. It will be remembered that the Chinese had earlier adopted the Confucian theory as the basis for their state, and the Japanese likewise accepted it without any trouble. The only controversial point was the problem of changing unsuitable emperors.

This attitude toward Confucianism was to persist among the ruling classes, and in the Tokugawa period Confucianism was taught with reference to the concept of the state (kokutai) by almost all the schools and individual scholars of Confucianism, including Ito Jinsai, Yamaga Soko, Yamazaki Ansai and the Mito school. Japanese Confucianism, associated with the nationalism of the Japanese people, asserted its superiority over foreign systems of thought.

Coming into contact with foreign cultures and becoming acquainted with Chinese philosophies and religions, however, the Japanese adopted much and in particular absorbed Confucianism, especially its social doctrines, which teach conduct appropriate to a human nexus. The views of Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu are inclined to a life of seclusion in which one escapes from a particular human context and seeks tranquility for oneself in solitude.

Such was not to be the taste of the Japanese at large. In contrast, Confucianism, and not Taoism, principally determined the rules of conduct in a system of human relationships. With regard to Buddhism, however, certain problems arose, for Buddhism declared itself to be a teaching of otherworldliness. The central figures in Buddhist orders were monks and nuns, who were not allowed to be involved in any economic or worldly activities.

Ogyu Sorai (1666-1728) a peculiarly Japanese Confucianist, positively advocated activism, rejecting the static tendency of Confucianism in the Sung dynasty (960-1279). The practice of quiet sitting and bearing reverential love in one’s heart Ogyu ridiculed: “As I look at the Chinese Neo-Confucianists, even gambling appears superior to quiet sitting and bearing reverential love in one’s heart.” He recommended learning useful in practical life.

Such was the mental climate that nurtured the economic theory of Dazai Shudai (1680-1747) and the legal philosophy of Miura Chikkei (1688-1755). Whereas Chinese Confucianism in the Sung surpassed the Japanese Confucianism that followed it in the contemplation of metaphysical problems, Japanese Confucianism directed its attention to politics, economics and law. Ogyu gave more attention to wu (things) and less to li (principle).

The great sage kings of the past taught by means of “things” and not by means of “principles.” Those who teach by means of “things” always have work to which they devote themselves; those who teach by means of “principles” merely expatiate with words. In “things” all “principles” are brought together; hence, all who have long devoted themselves to work come to have a genuine intuitive understanding of them. Why should they appeal to words?

Ever since the Tokugawa period (1615-1867) the schools of Chu Hsi and Wang Yang-ming have been energetically studied in Japan, but it is a question how far Japanese scholars were truly sympathetic with them. It is likely that Japanese Confucianists did not much care for metaphysical speculation. Absence of theoretical and systematic thinking is equally characteristic of the former scholars of Japanese classics.

B.

In the book by Herman Ooms (Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, 1998) we are offered a more dynamic and particularist view of traditional thought in the Tokugawa period. Against the view that Neo-Confucianism supplanted Buddhism, Ooms argues that “the harmonious coexistence of the three teachings (including Taoism) was at least as strong an intellectual current as the militant reaction against one of them (Buddhism).” Ooms integrates thought into its political and social contexts. “The practical world of political society, power, economics and history had no legitimate autonomy but was absorbed and dissolved into the two poles of man and the cosmos,” a system that he calls “a philosophy of ‘anthropocosmos.’” “The period under investigation covers slightly over a century, from the time that Oda Nobunaga came to power in the 1570s to the reign of Tetsuna, the fourth Tokugawa shogun, who died in 1680; the gestational, formative and maturing period of the Tokugawa order.” In its self-representation the warlord class that he studies “underwent a total turnabout,” converting benevolence (in Japan a primarily Buddhist rather than Confucian virtue), into a power “dispensed from the tip of a sword” as warlord power transfigured into sacred authority. “Confucianism was helpless with regard to the central issue that gave the sixteenth century its mercurial quality: power ― how to maximize, maintain and manage it.”

Instead of philosophical texts, Ooms depends upon “house rules,” such as The Seventeen Articles of Asakura Toshikage (1428-1481) and Tako Tokitaka House Code (c. 1544).

Many of the war lords whom Ooms studies, such as Nobunaga, considered themselves to be a combination of king, emperor and god, and their writings about themselves, or those that they commissioned to memorialize themselves, take the form of apologetics for their policies. Seeking to justify himself as a divine ruler, Nobunaga created a symbolic universe about himself to reinforce his claims. Central to this was a seven-story castle, 150 meters high, its functional space filled with waiting rooms and audience halls for his vassals.

Visitors entering at the ground-level basement under the first floor were confronted with a Buddhist Stupa, placed in the center of an open space that reached up to the third floor. The stupa honored a Buddha mentioned in the Lotus Sutra, Prabhutaratna, who arose from underground and represented the center of the cosmos. This centrality was to be all-comprehensive and include the great traditions. The decorations of the two top floors pictured key figures, respectively, of the Buddhist and Confucian traditions (in the latter case, the sage kings, Confucius and his main disciples). The first floor also contained a room dedicated to a popular Shinto deity, Bonsan, represented by a mound of pebbles.

Nobunaga arranged a stage from which to preside over the Way of Heaven. The Japanese term for castle keep is tenshu, “Heaven’s keeper”; according to Naito Akira the term refers to the Nijo-jo and to the Azuchi-jo. It may well owe an intellectual debt to all religious traditions of the time, including Roman Catholic (Tenshu-kyo, Teachings of the Lord of Heaven), but it primarily embodies the concept of the harmonious coexistence of the traditions, the Way of Heaven, tendo. This ecumenism points to the prominence of religion in Nobunaga’s overall scheme for political hegemony. From this platform he arrogated to himself, and administered, adjudicative powers in the realm of religion and ideology.

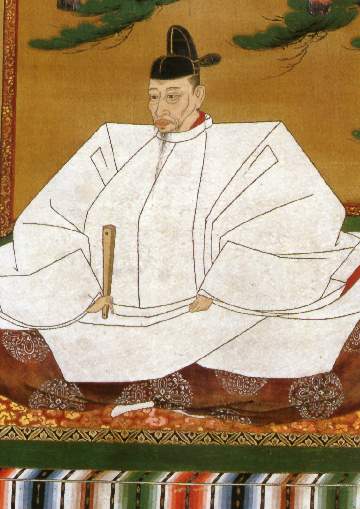

“The careers of Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyas,” says Ooms, “follow a path quite similar to that of Nobunaga.” “Ever more extravagant fortified palaces were being built and destroyed at a dizzying pace in and around Kyoto: Nobunaga’s Nijo palace in 1569 was followed by those in Azuchi, Osaka, Hikoto (the Jurakudai), Fushimi and finally Ieyasu’s Nijo-jo in 1603 and Iemitsu’s expansion of it in 1624-1626. . . . These palaces were the visible, colossal signs of the authority and power that their builders had won at one point or another, and they lasted no longer than the political base that they were intended to symbolize.”

Japan as the land of the Gods

Japan as the Land of the Gods contrasts with the pernicious senmon or “exclusivist doctrine” of the West. Appropriating the teachings of Yoshida Shinto, Hideyoshi writes:

Ours is the land of the kami, and kami is mind (kokoro), and the one mind is all-encompassing. No phenomena exist outside it. Without kami there would be no spirits, or no Way. They transcend good times of growth and bad times of decline; they are simultaneously the Yin and the Yang and cannot be fathomed. They are the root and source of all phenomena. In India they are known under the name of Buddhism; in China, under the name of Confucianism; in Japan, under the name of Shinto. Accordingly, to know Shinto is to know Buddhism and Confucianism.

Hideyoshi’s project was to unify the whole world under Japan. His ambition was to subdue China. He began by subduing Korea, which became “an exercise in kulturpolitik: the realization of a unity that is already there and only calls for implementation.” Hideyoshi elaborates on the political aspects of this East Asian cultural sphere: Here, he says, proper social hierarchies are upheld between rulers and the people, between fathers and sons, because they are based on adherence to the principles of jin (humaneness, in Chinese, jen) and ui (righteousness, in Chinese, i) . . . Buddhism also held an important place in Hideyoshi’s plans for the nation. “He ingratiated the Buddhists by restoring temples and issued laws regulating their affairs, thereby co-opting popular Buddhism.” As a variant of the Neo-Confucian emphasis upon the triad, Heaven, Man and Earth, Tokugawa Ieyasu developed the subjective aspect of the middle term into an emphasis upon “Oneself”: “To expand the principle of oneself is to fill it with Heaven and Earth; to reduce Heaven and Earth’s principle is to hide Heaven and Earth in one’s mind. . . . One can never go wrong by comparing things to oneself.” Herman Ooms generalizes:

Nobunaga, Hideyoshi and Ieyasu were self-made men. Through their cunning strategies they refashioned history. As Jürgen Habermas argues, however, “strategic action” (of which military conquest is but the purest example) as motivated by self-serving intentions, can never lay claim to truthfulness. . . . The results of such action will not be accepted by others beyond the immediate threat of coercion. In order to have themselves accepted, these rulers had to resort to a different mode of action that could validate such a claim. . . . ‘Symbolic action’ through which they sacralized their position, achieved their goal. This symbolic action was inherently ideological, because it bore on power and authority in a public way.

To offer yet another paraphrase of my own: Ieyasu regarded symbolic action as a requisite for recognition, just as Hideyoshi, symbolic temple iconography. More crucially, both sought a sacralization of their own position. For them the symbolic was inherently ideological. There can be no clearer indication that philosophy (in the free-spirited sense) was replaced by ideology (in the political and religious senses). As for the expansion of the self in Ieyasu’s statement, Ooms glosses it with a quotation from Chang Tsai: “By enlarging the mind one can enter into all the things in the world. . . . The sage . . . regards everything to be his own self.” “Self” here has little to do with subjectivity and everything to do with power. By incorporating Heaven and Earth into it, the Self becomes authority. Since the Self resides in the Body, the latter is then elaborated metonymically so as to correspond to an earlier conception of Heaven. “The metaphor of the Body,” says Ooms, “is a very powerful one. The human body is the one specific kind of natural resemblance among men that everyone recognizes and that permits collective comparison. It is the one thing in nature that is internally experienced.”

The next important figure in this development is Razan. “A virulent anti-Buddhist and proponent of Neo-Confucianism, he became a protégé of Itemitsu’s, was allowed to found schools, and his exact doctrinal positions were never too closely examined. The trajectory of his career indicates that Neo-Confucianism was never perceived by the early Tokugawa shoguns as a tradition deserving special support. It was not,” says Ooms, “a state ideology or orthodoxy. Shinto had been amalgamated with Confucianism and Neo-Confucianism since the Muromachi period, especially in the Kiyohara and Yoshida schools. Although Shinto theologians such as Bonsun and Yoshikawa Koretaru continued this tradition throughout the 17th century, many Neo-Confucian scholars also included Shinto interpretations in their writings. Some found in Shinto a religious tradition that was missing in Neo-Confucianism (Toju). The microcosmic-macrocosmic metaphoric operator underlies and unifies the various arguments, conceptualizations and doctrines through which the tendo world view is constructed. This epistemic operation is briefly revealed in Ieyasu’s Testament.” Razan elaborates on its principle:

The ancients saw the past through the present, Heaven and Earth through the body, Yin and Yang through the ether (ki). They saw the mind through the gods. There is no need to seek far for other things: one can see all things through man’s body; the ancients took Heaven and Earth and made it an exemplar or metaphor (tatoe) of the mind. . . . Now one has to take Heaven and Earth and apply them to man; if, however, one considers Heaven and Earth only as Yin and Yang and does not apply them to the body, one does not know the deep meaning of the scripture.

“The gods,” then, “are the basis of Heaven and Earth. Gods are the spirit of the mind; mind is god, or mind is the divine in man,” says Razan elsewhere. “The mind is the dwelling place of the gods; the sacred place where the gods dwell; even the himorogi, divine shrine of the Nihongi, is nothing other than the mind and the pure brightness of the mind nothing other than the divine light.” “Nature’s principles and the original principle of man’s mind are the same.”

Ikki (to paraphrase Ooms) is the primeval chaos (konton) of the Nihongi from which sprang the Yin and Yang deities Izanami and Izanagi. They in turn gave birth to the five gods of the Five Evolutive Phases that produced man. The gods manipulate these phases like marionettes. In Ikki or konton [in Chinese, hun tun] the principles of gods originated spontaneously ― a process like the origination of thoughts in the mind. Kunitokotachi is the first of the Heavenly Gods. Amaterasu is the first of the Earth Gods. Kunitokotachi, through a fissure in his body, created Heaven and Earth. It is through him that man’s basic mind can penetrate everything. Shinto existed before Japan had a written language. Divine words were truthful, because they took Heaven and Earth as their “text” and adduced the sun and moon as proofs. “It was a natural, not a man-made language,” says Ooms, “only later transcribed in (Chinese) characters.” Thus Tokugawa thought at base is a symbolic system not a discursive philosophy. In Mary Douglas’ words (as quoted by Ooms), “the symbolic mode insidiously seduces the intellect . . . as if the symbolic mode had overwhelmed the freedom of the mind to grapple with reality.”

C.

Ooms on Yamazaki Ansai, a Japanese Neo-Confucianist:

Heresies Refuted advertised its author as one who had mastered the essentials of Neo-Confucianism. Ansai proceeded along two lines. One was a straightforward exposition of key Neo-Confucian terms such as the triple concept of Nature, the Way and the Teachings; the virtue of reverence (kei; in Chinese, ching); fundamental distinctions such as those between the Elementary Learning and the Great Learning and between the applications of the teachings in ordinary and exceptional circumstances; and, of course, the Five Relationships, concerning which he singled out a text, buried in the seventy-fourth chapter of Chu Hsi’s Collected Literary Works, “The Precepts of White Deer Grotto Academy.” Ansai stressed that the concepts concerning the Five Relationships were not mere rules that someone had made up. Their normative power lay in the fact that they were lodged within one’s body or self.

A second approach of Ansai’s contrasted Neo-Confucianism with Buddhism. For him the latter’s crucial fallacy lay in the thesis that nature (sei) was emptiness or nothingness. Consequently, it lacked a theory of mind-heart. Confucianism, on the other hand, held to a fullness of mind, programmed as it was by the Five Relationships, which were governed by the Five Virtues (humaneness, righteousness, propriety, wisdom, faithfulness). Actually, the Buddhist theory of the mind’s emptiness, rather than a pronouncement about the metaphysical status of the mind as it functions in the world, was a normative ideal to be achieved ― like the Five Relationships ― and could very well, in the hands of a Suzuki Shosan, serve as the linchpin for a concrete ethics that differed little from Confucian ethics. In Ansai’s view, Buddhism taught that the mind was empty and dead, Neo-Confucianism, that it was active and full.

Later Ansai was to follow Chu Hsi, who had restored the text of the Book of Changes and viewed the work primarily as a divination manual. Ansai’s interest in the I Ching is an aspect of his scholarship that has often been overlooked. Like Chu Hsi and all Sung scholars, he spent considerable time and energy studying this work. His four-page autobiography, replete with Shinto items (poems, visits to shrines, and so on), refers in only three places to Confucian works: to his reading of the Elementary Learning and some of Chu Hsi’s poetry, to the content of his first lecture series, and to the publication of the Kohanzensho, i.e., Complete Writings on the Hung Fan, or Great Norm, a chapter from the Book of History and the first Chinese text to speak in numerical categories about the correlations between Heaven, Earth and Man, the Five Evolutive Phases (Wood, Fire, etc.) and the Supreme Standard (for the ruler’s virtue).