- Confucian values in Bushido

- Confucianism and Neo-Confucianism

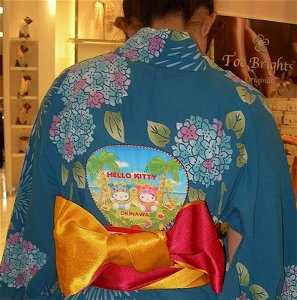

- Confucianism in Japanese art

- Confucianism in the context of a non-philosophical culture

- Confucianism as a religion squeezed out by “the System”

- Confucianism in modern Japanese society

Quoted/adapted from Karel van Wolferen, The Enigma of Japanese Power, originally published in 1989

Blunted Confucianism

The malleability, relativity and negotiability of truth in Japan; the claimed superfluity of logic; the absence of a strong intellectual tradition; the subservience to the administrators of law; and the acceptance, even celebration, of amorality; these, of course, are all casually intertwined. They reinforce what I have referred to as the crucial factor in the exercise of Japanese power: the absence of a tradition of appealing to transcendental truth or universal values.

It is helpful in examining the mental background of the Japanese political tradition to make a comparison with intellectual and spiritual life in China. The dominating force there was Confucianism, a surrogate religion with roots in social experience, and thus very suitable for Japanese power-holders. Confucianist ethics were based on a sophisticated understanding of human character and the dynamics of society; metaphysics had no place in it.

The Chinese concept of heaven (t’ien) is very different from the western (originally Mesopotamian) concept of a universe that was created, and subsequently controlled, by a Divine Power. The Chinese Heaven was, of course, viewed as superior to anything on Earth, but it was not seen as the creator of the universe and was not visualized in concrete form. Nor was it considered important as a source of social knowledge.

The Confucianist code of behavior could hardly be more this-worldly in its orientation. Significantly, though, the principles that it developed were taken to be universally true. This prepared the Chinese mind to conceive of a moral order separate from the social order. Though not based on any belief in a supernatural being or supported by metaphysical speculation, it transcended temporal authority and immediate social concerns.

However much the Japanese emulated the Chinese in other things, and however much Japanese power-holders craved obedient subjects, they were not interested in trying to produce moral citizens by invoking paramount abstract principles. To follow the Chinese one step further and, by abstracting a morality from socially desirable behavior, to develop the idea of individual conscience in potential opposition to social practices was totally inconceivable.

The Chinese individual can draw upon a tradition that instructs him not to surrender his moral judgment to society. As Confucius is supposed to have said: “The moral man must not be a cipher in, but a cooperative member of, society. Wherever the conventional practices seem to him immoral or harmful, he not only will refrain from conforming to them but will try to persuade others to change the conventions.

Confucius rejected absolute loyalty to an overlord in favor of loyalty to principle, to the Way. The result was “a goodly company of martyrs,” who have given their lives in defense of the Way. This tradition has given the Chinese, at the very least, the freedom to speculate on the legitimacy of rulers. The revolutions and usurpations of the throne that punctuate Chinese history were always justified as the mandate of Heaven.

Even for the great mass of people, the concept of a moral order transcending considerations of political or economic expediency provided something to which they could, at least in principle, appeal so as to free themselves from the total arbitrariness of power. The place that the Chinese have given to abstract principles, the power that they have granted ideology, could hardly be better illustrated, for example, than by The Cultural Revolution.

Confucianism as a religion squeezed out by “the Japanese System”