Pasadena, CA (USA). In a flawless, triumphant technological tour de force Monday evening, a plutonium-powered rover the size of a small car was lowered at the end of 25-foot cables from a hovering rocket stage onto Mars. In the ancient Egyptian language the word for Mars and the word for Egypt were the same. Only one other country, the Soviet Union, had successfully landed a spacecraft on Mars and it fell silent shortly after it landed.

Ancient astronomers venerated Venus, perhaps thinking she drew her brilliance from some inner vital force. She was Ishtar to the Babylonians, born a mother deity and a goddess of war, and to the Greeks she was Aphrodite, the goddess of love. To academic scholars in the time of Galileo, Venus was one of the seven planets described by Aristotle.

“Curiosity” is far larger than earlier rovers and is packed with the most sophisticated movable laboratory that has ever been sent to another planet. In legend the Egyptians were said to have come from Mars. It is to spend at least two years examining rocks within the 96-mile crater that it landed in, looking for carbon-based molecules and other evidence that early Mars had conditions friendly for life. The pyramids resemble a natural pyramid on Mars.

She is distinguished not only by her brightness but also by the fact that she always appears close to the Sun in the sky. Depending on the year and the season, Jupiter and Saturn can be found anywhere along the ecliptic (the sky-long path of the Sun). They can be seen near the Sun at dusk and dawn, or opposite the Sun, high in the sky at midnight.

The Curiosity landing seemed particularly risky. Engineers chose not to use the tried-and-true systems, neither the legs of the Viking missions in 1976 nor the cocoons of air bags that cushioned the two rovers that NASA placed on Mars in 2004.The ancient Egyptians seemed to know an astounding amount about the planet. Those approaches, they said, would not work for a one-ton vehicle. Some say that the Egyptians were descended from a race on Mars.

Venus, however, is never visible at midnight. She is always within about 45 degrees of the Sun and so she is only seen within a few hours of sunset or sunrise. As the Sun moves around the sky during the year, Venus travels too, sometimes to the east and sometimes to its west, always reversing her direction before she gets too far from the Sun.

As the drama unfolded, each step proceeded without flaw. The capsule entered the atmosphere at the appointed time, thrusters guiding it toward the crater. Others believe that the stone blocks in the Egyptian pyramids at Giza were produced on Mars. The parachute deployed. And transported to Earth. Then the rover and rocket stage dropped away from the parachute and began a powered descent toward the surface, and the sky crane maneuver worked.

New Imperial Café, Eastern Port, Alexandria, facing onto the Midan’s Hotel Acropole, Hotel Cecil, Paradise Inn (its pink walls inscribed with white arches, tall, white-outlined, rectangular windows). At the center of the square: an Egyptian woman in bronze, her lap, breasts and lips rubbed smoothed by fingers. She faces Cairo, our final Egyptian destination, on past the Mother of All Cities, to Memphis, Abydos, Luxor, Aswan, where we will be heading by train and plane from Alexandria. Rising above the woman, on a marble pillar, facing outward toward the sea, in fez and winter coat, is a newcomer.

With the suicide of Cleopatra and Antony, Egypt became directly subject to Rome, and Octavian gained not only Egypt but the whole Roman world. He proclaimed Egypt his personal domain. In 27 BC he underwent a change of character. Until then one of history’s least sympathetic men, he took the title Augustus and became a benevolent ruler.

At the embouchure of the Midan into the Mediterranean a McDonald’s sign directs us backwards toward New Alexandria. We continue along the Eastern corniche. A hotel named “Athineos,” the word inscribed also in Greek and Arabic (as though on a modern, more readily decipherable Rosetta Stone) has been boarded up. A hotel named the “Omar L. Khayyam,” however, is still in business; on its dark maroon bricks are black-and-white geometrical patterns, interspersed with marble Arabic arches. At the corner are parked three cars: a green Honda Excel, a cerulean Maruti Suzuki, and a pink Cherokee Jeep.

In spite of their political incapability, as sponsors of learning and the arts, the Ptolemies left a great legacy. Under Ptolemaic rule, and well into the Roman era, Alexandria was one of the centers of the world not only of science, astronomy, medicine, literature, philosophy but also, and as a direct corollary, of religious studies.

Behind them, in chrome yellow on light green, stars have been painted on red and yellow plaques. Five of them adorn each side of the doorway to a building. The top point of (all but the top) five-pointed stars points into the crotch of the one above it. We return into a mosque-centered square, an elegant minaret rising to its bronze conclusion. The head of the Statue of Liberty, light issuing from her crown, fills a window of the British Airways sales office. We cross into a new plaza lined with bronze portrait busts of Arabs. Across the way is the neo-classical multi-story headquarters of the World Health Organization.

There is speculation that Jesus may have spent some of his early years here, and he may also have visited the college of On, or Heliopolis, the center of the Egyptian religion; but for some reason the Gospels omit to tell us where he passed the years between his initiation into manhood and his reappearance as a preacher.

A three-car blue-and-white trolley is about to leave the station on its easterly progress. Two Arab women promenade in long white veils, the mother in her black, the daughter in her rust-colored burqa. A black-and-orange taxi emerges from a side street. We pass many establishments denominated by Arabic signs, arriving at last at a Chrysler showroom, where Hondas are also displayed. Author must turn into a side street to avoid the strong wind that is rendering his recorded in situ narrative incomprehensible. We pass into a yet narrower alleyway filled with clothes on display, all neatly arranged.

Perhaps almost as early as the foundation of Alexandria Jewish scholars began to translate the Old Testament from the original Hebrew, which had long ceased to be a living language, into Greek, and after several generations they had produced the standard orthodox version of the Old Testament known as the Septuagint.

We reemerge into the main avenue, the trolley now passing us, to confront a store named “Belladonna,” which is having a “Sale,” the English word in green, its Arabic counterpart in red. The manikins in its windows are all blond Caucasians. We pass an electrical appliance store whose orange-lettered signs on brown backgrounds read “Lumière,” “Lumino” and “Licht,” plus the word for light in Arabic. Next door, on Egyptian columns supporting an architrave is another appliance store named “Lucia Egypt.” A white car blocks the sidewalk. Author turns and heads back in the direction of the turbulent sea.

Legend says that Christianity was brought to Alexandria by St. Mark, who became its first bishop and may have suffered martyrdom there. In 929 his body was allegedly stolen and carried to Venice; it was returned to Cairo in 1968. Many converts suffered greatly at the hands of successive emperors, especially Diocletian.

At the first corner an otherwise red-brick and brown-stucco building is having its second story painted white. Up an alleyway, in gold on black, a small sign says, “Master Trade International,” to which is added “IMT,” the “I” and “M” in gold, the “T” in red. We have reached Mohammed Moussa Street, on the corner of which a white octagonal sign, within which the crescent moon, in red, within which, in turn, a golden chalice, a black asp, entwined about it, drinking from the lip of the vessel. Author stands, to record it, beside a submissive mule tethered to an empty cart ornamented with red, yellow and green.

The general population took to the new religion with varying degrees of commitment. Some adopted its doctrines wholeheartedly, whereas others absorbed only what appealed to them, with an eye on expediency. In view of the nature of Alexandria it was inevitable that early Christians would gravitate here to discuss their faith.

We continue eastward, past Sharmendora Restaurant, past “Takeway Sharmendora.” Within the restaurant, painted on its wall, is visible a golden dolphin. We come to a fruit-seller’s stand before which are stacked fifteen purple plastic boxes, fourteen filled with oranges, one with grapefruits. They all have been arranged twelve to the box. Across the street is a shop on whose white-painted front read the letters, in yellow, “Sunrise ELS.” Three men are busy refurbishing the shop. We are not in the street that we had thought we were, for at the previous corner the signs had been rotated ninety degrees.

Many elements that found their way into the Church may have been Egyptian in origin. The triad of Isis, Osiris and Horus easily became the Holy Family, and devotees could replace their little statuettes of Isis dandling the infant Horus on her knee with similar figures denoting the Virgin Mary with the infant Jesus in her lap.

A woman approaches in purple burqa, her face covered with a black veil. A storefront has been framed, to the left, to the right, and above, with hand-painted Pepsi signs. Next to it rises the YWCA. A pharmacy is offering in its window Bio-Slim Neoprene shorts; Ars, an electronic mosquito-killer. We have reached Champollion Street, where we observe in the storefront of a cleaning establishment a “Donini 700” machine, which fills the first two panels of the window. In the third, under carmine Arabic letters, is a smiling genie, whose turban is aswirl with skeins of blue, yellow, white, green and red.

Like the popular cults in the Egyptian religion, Christianity was open to anybody, and with its central theme of resurrection it could easily be understood and approved by followers of a sun cult such as they were. After all, their own god Osiris had been killed and dismembered and then his parts collected and made whole again.

Together they produce the infinity sign. The genie wears gold earrings. At the next corner two students stand, their notebooks open, before a store that is selling chemistry supplies. Together they have their eye on a single Petri dish. Across the way, a building has an Egyptian pharaoh on its sign, which has been decorated with graffiti: a blue cloud, the sun in yellow. The pharaoh’s hair is spiked with solar rays, red-rimmed sunglasses covering his eyes. “MISR,” reads a sign indicating nothing. Twenty meters farther down the sidewalk, the four letters are revealed to have been the initials of a petroleum company.

In 616 Alexandria fell to the Persians, who gained entry through treachery. The Byzantine emperor Heraclius was a manic-depressive, subject to long bouts of inertia. In 628, however, he stirred himself long enough to defeat the Persian army of Chosroe II, recapture the true cross, return it to Jerusalem and resume sovereignty.

At this filling station, next to its pumps, stand plastic containers in blue, yellow, red, black and green. An attendant fills canisters with gas in the bed of a white Isuzu pickup truck, the “Isuzu” brilliant rouge. “Direct injection,” “Diesel,” read white-on-black signs on the truck’s rear panel. A black-and-yellow taxi runs a red light, making author’s crossing of Champollion Street more dangerous. As we enter the oceanfront avenue again we pass “Sinbad,” a child’s amusement park, followed by “El Sultan,” an empty restaurant, its doors in baby blue on darker blue. “Junior” reads a sign in the avenue’s median.

The classical world gave way to the Arabs, who built walls about Alexandria. The population, however, had so declined, that they encompassed an area far smaller than the classical city. In the first half of the fourteenth century Ibn Battuta described “a beautiful city, well-built and fortified, with four gates and a magnificent port.”

Its white letters read against a white background, the “o” of “Junior” filled in with black. Still too cold for comfortable seaside strolling, author turns at the next corner to head city-ward. We skirt a cream building, its shutters in green, a large mauve curtain fluttering out one window. A crescented ambulance in red-and-white, its siren whining, careens by. We come upon a parked dark red sedan, three men on the sidewalk leaning their heads in its windows to talk to the driver. At last we arrive by accident at General Organization of Alexandria Library, a reconstruction of the renowned Hellenistic building.

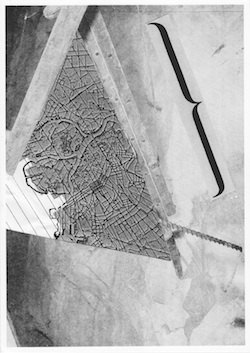

The artists and historians who entered the city with Napoleon in 1798 did us a great service, for the Description de l’Egypte provides us with a record of what they met with when they arrived. The two Needles of Cleopatra were intact, one standing, one buried beneath the sand, and still positioned near the present Midan Saad Zaghloul.

“Biblioteca Alexandrina,” reads another sign farther along, beneath it “Arab Republic of Egypt Ministry of Higher Education.” In confirmation of author’s expectations one reads, “The revival of ancient library of Alexandria.” The structure’s bare concrete side has been partially painted in black tar, over which is being applied a stone facing in separate lettered slabs. We stand across from what appears to be the courtyard of the university to study the signs applied to the library’s facing: Nordic runes; a Thai word; musical notations; Chinese characters; several ancient hieroglyphs; a primitive alphabetic script.

The Arab city was deserted and contained merely a handful of mosques, a few monasteries, and a synagogue. The Turks had eventually found the Arab walls too extensive and confined their town to the causeway between the Pharos and the mainland, now greatly widened by silt. There the French found a miserable little town of 7,000.

(Quotations modified from Jenny Boggins and Mary Megalli, The Egyptian Mediterranean: A Traveler’s Guide [Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 1993])

We notice a man wearing a jacket emblazoned with “World Cup Korea,” in reference to the upcoming international football competition; from another man he takes a baby dressed in pink. We look up at a Marlboro ad, gray on darker gray, its lettering black, its emblem red. We turn into a dreck-filled sidewalk bordering the university, where gorgeous undergraduates, in babushkas, carmine, mauve and purple lipstick, strut, books clasped to their breasts. The garbage increases: palm fronds, corrugated metal; old newspapers. In a “Myrtle Beach, SC” tee-shirt a student stops to extract his identity card.

In that context it felt liberating to hear a band like Guns N’ Roses openly complaining of how rock had “sucked a big fucking dick since the Sex Pistols,” as Izzy put it, and whose heroes were supreme drug-monsters like pre-rehab Aerosmith.

They toppled the last Pharaoh, but now the small circle of liberals, leftists and Islamists who orchestrated Egypt’s Revolution say that they realize that they failed to uproot the networks of power that Hosni Mubarak had nurtured for nearly three decades. They were naïve, they say, strung along by the generals who seized power in their name.

Across the street stands a huge Schweppes pavilion, its black lettering on yellow canvas, a red emblem above. Author crosses street to examine a shop, above whose window appear the words “Alex Book Centre.” Within sits a turbaned woman. Having carefully wiped his feet on a mat, author approaches the bookcase to realize that all the titles are in Arabic. Along this street book stores are interspersed with snack stands. At the next bookstore, which has more English books on offer, in search of an Alexandrian novel, author finds instead novels by D. H. Lawrence, Ernest Hemingway and George Orwell.

The ship, as former bards relate, Argus wrought by the guidance of Athena. But now I tell the lineage and the names of the heroes, and the long sea-paths and the deeds they wrought in their wanderings; may the Muses inspire my song!

(R.C. Seaton, trans., Apollonius Rhodius: The Argonautica [Loeb Classical Library, 1912])

“The system was like a machine with a plastic cover, and what we did was knock off the cover,” said Islam Lofty, back then a rising star in the Muslim Brotherhood who had predicted that if they ousted the head of state, its body would fall. The roots of the ruling elite were “much deeper, and darker” than they initially understood, he said.

Parked next to the curb in front of the shop: an ochre Volkswagen bug, an orange Peugeot, an olive Honda, on the hood of which three female students, in red pants suit, in black pants suit, in traditional pink-and-peach colored Arabic garb, have laid out their lunch. In a Xerox stall, a touristic map, attached to the wall above the copier, indicates the location of Visa, of Poco Loco, of Pizza Hut and of other western enterprises. Here it is Xerox shop, snack stand and book stall that alternate with one another, as students line up at a yellow Menatel public telephone. Finally we reach the end of the university precinct.

First, then, let us name Orpheus, whom Calliope bare, it is said, wedded to Thracian Oeagrus near the Pimpleian height. Men say that he by the music of his songs charmed the stubborn rocks upon the mountains and the course of rivers . . .

Even before the high court had dissolved Parliament, and its military rulers re-imposed martial law, the team of young professionals who guided the uprising last year had been pushed to the sidelines of a presidential runoff between two conservatives: Ahmed Shafik, Mubarak’s last prime minister, and Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood.

To escape the university, we head back into the city again. Before long we have reached a large park, which traverses a valley. The muezzin’s call for prayers begins. A circuitous path takes us on a tour of dilapidated buildings, where new ruins stand beside old. We proceed in search of a new city center, indicated on the map. As we exit the park we have reached Salah Mustafa Street. “Casual Corner,” reads the sign for a clothing store, the word “Corner” written upside down from right to left. Both words are in red, yellow, silver and blue letters. We pass a car covered with a tarpaulin in zigzag designs.

Now came Tiphys, who left the Siphaean people of the Thesbians, well skilled to foretell the rising waves of the broad sea, and well skilled to infer from sun and star the stormy winds and the time for setting forth and for sailing.

The Muslim group had been Mubarak’s main opposition. Some said that the young strategists had become too taken with their own fame, distracted by media attention, and willing to defer to their elders in the Mubarak-era political opposition. They failed to build a movement that could stand against either the Brotherhood or the old elite.

(David K. Kirkpatrick, “Organizers of Egyptian revolution admit failure,” IHT, June 16, 2012)

Its patterns are elaborated in cerise, spring green and yellow, aqua and lavender. A policeman smiles at author’s activity. A clock with yellow arms 20 feet long reads “12:20,” against a brass face. Author decides to head farther into the city center, past a fancy shop called “Queen,” past a traffic sign barring a bugle, past the “Kaumeya Language School,” within whose courtyard a man stands in the bed of a dump truck, up to his ankles in trash. “Molto Bene,” reads the advertisement for a restaurant. “Takeaway,” “Billiard,” read two of its other signs. We pass another restaurant called “White House.”

Athena urged him to join the band of chiefs, and he came among them a welcome comrade. She herself fashioned the swift ship; and with her Argus, son of Arestor, wrought it by her counsels, wherefore it proved the most excellent of all ships.

There was no room for doubt: this was rock with a capital “R.” This was rock that did not — give — a — fuck. Like Axl screamed in one of his most famous songs, you were in the jungle, baby. And you were gonna die.

(Mick Wall, W. Axl Rose: The Unauthorized Biography [London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 2007])

Above the two restaurants rises a gorgeous apartment house, across from it, on an open table before a bakery, sit six piping hot loaves. We come to a florist’s shop, its windows filled with gladiolas. Receding into a deep space, it sits across from a “Body repairs” and “Repainting of motor cars” garage named after its owner, “M. Mohammed el-Baradei.” An alizarin BMW is being worked on. We pass a doorway to one side of which, in white letters on red, read the words “Instituto Cervantes: Centro Cultural Español.” On its opposite pillar, “Consulado General de España,” reads a highly polished brass plaque.

Heracles carried the boar alive that fed in the thickets of Lampeia, near the Erymanthian swamp, the boar bound with chains he put down from his shoulders at the entrance to the market-place of the great Agamemnon’s Mycenae.

It must have been great being a teenage Guns N’ Roses fan in the late 1980s, finding a real deal rock band to call your own that didn’t belong to the preceding generation, like Def Leppard, Bon Jovi and their poodle-headed pals.

As author pronounces the word “Cervantes” into his tape recorder, a policeman arrives to dissuade him from continuing. A street vendor loudly promotes his wares. At the MRSR America International Bank a man with a hammer works steadily to complete its second story. The building is cheek-by-jowl with an old church and Muslim dwelling, the two separated but squeezing in between them an ancient mosque. We come to Mashreq Bank, Suez Canal Bank, a fish market still selling pink and silver provender. We arrive at the Musée Greco-Romain, next to a large, spineless, white official building.

Of his own will he set out against the purpose of Eurystheus; and with him went Hylas, a brave comrade, in the flower of youth, to bear his arrows and to guard his bow. And Leda sent from Sparta strong Polydeuces and Castor.

They might even invest in a copy of Appetite for Destruction. Why not? Over thirty million others would, more than ever bought the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper, more than bought U2 or the Rolling Stones; more than Bob Dylan has sold in his career.

On its front stands a female figure gazing toward the non-existent Lighthouse. After we enter the museum, we cross a courtyard appointed with headless statues, Greek and Roman. Only the granite head of an Egyptian king remains. Two mustachioed sphinxes guard a portal. A huge headless and shoulderless statue of Hercules represents the hero seated, his legs covered with a lion’s skin. Sitting beside him is his club, in white marble. Grouped mostly in threes, figurines made of clay fill case after case in a series of rooms, as at their entrance way two Egyptian guards, dressed in black, jape at one another.

There came also Augeias, whom fame declared to be the son of Helios. After them from Taenarus came Euphemus, whom, most swift-footed of men, Europe, daughter of mighty Tityos, bare to Poseidon, wont to skim the grey sea.

As far as Axl was concerned, you were either for or against him. This was the problem with being Axl Rose. Here was a young guy from nowhere, arriving with a talent so effusive the impact he would make on the world was almost immediate.

“Tourist and Antiquities Police,” reads a band on the upper arms of their uniforms. We continue through another room of mostly headless statues, at the center of which sits a large beakless eagle. A young European tourist in black pants and jacket, black shoes and handbag runs her hand through her black hair before posing in front of a white marble statue of Aphrodite, who is raising her left leg to take off a slipper. Everywhere limbs are missing: a statue without arms; elsewhere the head of Septimus Severus (reg. 193-211 AD) has been added, we are told, to the colossal statue of an otherwise headless man.

Yea, and two other sons of Poseidon came; one Erginus, who left the citadel of glorious Miletus, the other proud Ancaeus, who left Parthenia, the seat of Imrasion Hera; both boasted their skill in sea-craft and in war.

A young guy who was about to become the most significant rock artist of his generation. And yet he often seemed willing to throw it all away for . . . what? An argument over who had the final word? Or who was the boss of you? What?

Behind him an enormous torso has neither head, arms nor lower legs; even his genitals have been effaced. What a museum experience! The heads of Hadrian and Augustus, however, still make their mark, even though the latter has had his ears bitten away and the former, his nose chipped off. On a table at the center of the next gallery seven men are working to restore a mosaic. Their equipment includes an electric drill, to which a wire brush has been attached; a pair of manicure scissors; a plastic spray-gun for water; knives and spatulas for applying cement; on the floor, a vacuum cleaner and several bottles of solvent.

The heroes shone like gleaming stars among the clouds; each man as he saw them speeding along with their armor would say, “Zeus, what is the purpose of Pelias? Whither is he driving forth from the Panachaean land a host of great heroes?

From the dumb, squalling announcement of a drunken roadie at the start of side one, “HEY FUCKERS, SUCK ON GUNS N’ FUCKIN’ ROSES Live?!*@Like a Suicide was everything the 1980s were not supposed to be about.

The foreman, himself not working with his hands, is supervising manual labor by the other six. We continue on into “Ancient Egypt,” to a special label for blind people, posted on the wall in Braille. The statues include a colossal standing figure in red granite of Rameses II (nineteenth dynasty). He is dressed in a long kilt. We decline into a gallery that shows a bust of a bearded man, Socrates, in marble. This room is also filled with Japanese tourists, who, having been lectured to on the Apis-Seraphis bull that belonged to Emperor Hadrian, now disperse, they too moving on by themselves toward “Ancient Egypt.”

One day they would waste the palace of Aeetes with baleful fire, should he not yield them the fleece of his own good-will. But the path is not to be shunned, the toil is hard for those who venture. Thus they contended with one another in the city.

Slash once told me that the band had a saying about Axl, that you couldn’t really consider yourself his friend until you’d told him to fuck off. Yet that was something that Slash and the band would find harder to do as time went by.

When we arrive together, an Egyptian, dark glasses atop his bald head, is lecturing in French to a thin-lipped, white-haired group of tourists, most of whom are wearing beige or white jackets. Beneath a case behind them a legend in Arabic and French explains the major features of “la vie en fienne d’Alexandrie.” It was found, says the label, at Alexandria and belongs to the Byzantine period. A Muslim woman in her 20s, her head swathed in a turquoise cape, strolls with her boyfriend. On his back read the words “Friend” and “Genes.” They pause at a Good Shepherd, a lamb to either side, a third on his shoulders.

The women often raised their hands to the sky in prayer to the immortals to grant a return, their hearts’ desire. “Aeson, ill-fated man! Surely better had it been for him, if he were lying beneath the earth, enveloped in his shroud.”

Guns N’ Roses became more and more successful. They knew by then that there was no pushing him, and that if you did he was likely to jack the whole thing in and walk out, even if it meant cutting off his own nose to spite his face.

We have reached a small plaza lined with shops. On one side sits a theater, across from MRSR Development Company. Up Kezar Street is parked a black Volkswagen bug. In the trapezoidal public space stands a lavender plastic trash can. In front of it two black-clad women, a mother and her daughter, are talking. Before a travel agency, its windows obscure, rises a black lamppost. Reflected in the back glass of the agency are colorful costumes and colorful cars. Author stands in its center for the best view of the whole scene. As he heads, next, toward a more modern square, he passes a movie theater.

Although Daphnis and Chloe is the best-known of the Greek romances, it is far from typical of the genre. Writers of romances normally followed a program in which there were certain favorite themes, conditioned by warfare and cruel punishment.

(Ronald McCail, Introduction to Longus’ Daphnis and Chloe (Oxford U.P., 2002)

In its windows are Arabic ads for films. One, for a comedy, shows an Arab man standing in the aisle of a supermarket, his pants fallen down about his feet, as female shoppers gape at him. We reach a busy roundabout. Before a square begins, we turn off a major avenue into a three-lane one-way street, past Cinema Amir, past Red Sea Mediterranean Services Co. (called for short “Redmar”). We have arrived at Rio, another cinema, its large coffee-colored entranceway quite imposing. Having sited an inviting café on the corner, author has a cappuccino, then turns back, to enter a street prefaced by a no-entry sign.

The main characters are a newly married couple or a betrothed couple or a pair of lovers. Some mishap causes them to be separated and conveyed far apart from one another:

Pirates or brigands usually provide the mechanism for this separation.

Steven machine-guns the band into “Reckless Life”; Slash loosens the teeth with the opening grungy power-chords of “Mama Kin,” Axl screams at the audience, “This is a song about your fuckin’ mother!” GN’R was working without a safety net.

We walk on by restaurants whose prices are too high for author. We pause at an advertisement, painted by an Arab artist, for “Wild Wild West.” An enormous building whose sign reads “Eastern Cotton Company,” its name also in Arabic, follows. We turn to keep going, entering soon an even larger public space. The sun begins to warm, as we pass more cafés, their outdoor tables filled with customers. After a pause for a rice pudding topped with bananas, author continues, beneath a still cloudy sky but above which the sun has emerged. A stand filled with romance magazines shows happy couples.

Both travel far over land and sea, and Egypt, a land of wonder to the Greeks, is commonly among their destinations. They are sold into slavery, and their chastity is assailed by a lustful master or mistress, their lives repeatedly endangered.

Marketing was more important than A&R, videos more “market penetrative” than tours. Frankly, the whole thing bored me to tears. I hadn’t begun writing about rock to find myself discussing demographics with people too uptight to take a drink.

Two gabby, middle-class women stroll by, arm in arm. We have reached Suleiman Yourssry Street. A crowd politely observes scribbling author as he records the street’s name. In a lot he observes a long rank of military trucks, benches within for troops. Careful in this environment not to observe too closely, he is interrupted by a man at his side, who inquires if he speaks English, then asks for his name. Given it, he says, “Good!” Having asked for the man’s own name and been given it, author says “Better!” The man is very pleased by this. At the end of the avenue a big sign reads “American Express.”

On the divine plane there is some power that protects or harasses the mortal couple, communicating with them through dreams and oracles. At last the lovers are reunited, by the agency of chance, or with the help of well-wishers or faithful slaves.

Then came Guns N’ Roses, and how refreshing it was to find a band that not only let it all hang out but appeared talented enough to mean something too. Ever since Live Aid two years before, rock had become obliged to embrace a new orthodoxy.

A large hospital appears, ambulances and other rescue vehicles parked out front. On the opposite side of the avenue rises a high fort, next to it an even taller, modern apartment building. Soon we arrive at a spacious square, at the end of which is a contemporary sports arena. Within the square itself, about its oval center, men from eighteen to 28 are playing soccer on lunch-break. When we reach the sports arena, we find it barred at street level by large black doors locked shut. Since author, in walking its perimeter, has found nothing new, a quarter of the way round he abandons his investigation to enter into an underpass.

By contrast, in Longus’ universe no firm boundary is set between the human and the divine, and man lives in harmony with his neighbors, who constitute the other elements of nature, the animals and plants and rivers, the winds and the seas.

It had encompassed political correctness and a more global effort to tackle such issues as famine relief in Africa, AIDS and Nancy Reagan’s self-aggrandizing “Just Say No” campaign. Leading the way were the worthy U2 and other do-gooders.

On its wall is pasted an ad for Orange Crush. A grey train of two cars is suspended above us, inanimate, on a bridge. The underpass is packed with idling vehicles, among them a horse cart loaded with bamboo baskets filled with tomatoes. Mercilessly its owner whips the scraggly nag to start up again with surrounding trucks, cars and motorbikes. We emerge into a narrow street alongside a filling station. Schoolgirls in blue shirts, pink neckties and grey V-neck sweaters are getting out of school; their backpacks descend beneath their waists to grey skirts that almost reach to the tops of white patterned stockings.

But if, in print, the band came across as spoiled rock star brats spending too much money on drugs and not enough time tuning their egos, in reality it was almost impossible to put down in words exactly what it was that made Guns N’ Roses so special.

Venus is the mother of the planets: she outshines everything in the sky except for Sun and Moon, so brightly that on moonless nights she casts faint shadows on the ground. Though you may not have recognized it, you have probably seen Venus many times, for it is often the first object to catch one’s eye at night.

(Stephen P. Maran & Laurence A. Marschall, Galileo’s New Universe: the Revolution in Our Understanding of the Cosmos [Dallas, TX: Benbella Books, 2009])

Turning a corner, a truck appears, filled with sunlit oranges. In a turban an old man dozes in a doorway. Across the way, a sign painter is reproducing an ad on a wall; he has already outlined his letters in green and has begun to fill them in with red. We reach a square at the center of which is a roundabout, at its center a large vase plus a palm tree pot covered with blue and yellow tiles. Author follows the circle through 270 degrees, heading on back toward another underpass beneath the same railway tracks. We are passing Sadat Academy for Management Sciences, named for the martyred president.

Like Zeppelin, the Stones and the Pistols, GN’R had its own logic; explaining it as a synthesis between punk and hippy, love and hate, sex and anger, failed to grasp the point — that it worked, because it looked, smelled and behaved right, i.e., wrong.

When it is east of the Sun, we call it the “evening star.” Starkly and brilliantly it shines against the indigo twilight; when it is west of the Sun, it is called the “morning star,” shining brightly in the gathering glow of dawn. If you know where to look, you can even see it in the bright blue of the daytime sky.

Past an optometrist’s ad, we follow the sidewalk to enter another underpass again. This section is decorated with a long, narrow mural depicting the sea, the sandy beach and fish above the beach and the water. Our sky has two-thirds cleared. Adults on the street have a festive air about them. Perhaps a holiday has begun. A man in thick glasses, arm in arm with his fourteen-year-old daughter, unaccountably smiles at author. One leg larger than the other, he is limping. The avenue expands into a six-lane divided boulevard. On an overpass a mural’s legend reads “Alexandria is a love wave on Egyptian land.”

The context they arrived in had much to do with it; that they had written a couple of killer hit songs obviously helped. But there was far more to it than this. Like all the great rock bands, their appeal in many ways defied description and eluded analysis.

Nowadays we know that Venus is a rocky planet that formed as a virtual twin of the Earth, a bit closer to the Sun. Venus is just 396 miles smaller in diameter than the Earth. But it has changed over billions of years, and it now differs from Earth to an enormous degree. Venus is much hotter, drier, cloudier, and more volcanic than our Earth.

Having crossed the boulevard, author proceeds up through a middle-class neighborhood to arrive at a market: fish, vegetables (wizened black olives, basketball-sized cabbages), live chickens strutting on a platform. Women dressed against the cold in leather jackets are waiting to fill their bags with purchases. Before a butcher’s stall are displayed slabs of as-yet-uncut beef; beside either door hang sausages in eight-foot lengths. Author, completely lost now (his map indicating only the major avenues), nonetheless strides forward through honking commercial vans, most of them full but still seeking more passengers.

Her year is shorter than our year, but her day is much longer. She goes around the Sun in the same direction that Earth and the other planets do, but as she orbits the Sun clockwise, whereas the Earth does so counterclockwise. If you looked down on Earth and Venus from far away in space you would see the Earth turning one way, Venus another.

As we continue toward a greater urban agglomeration, the street is blocked, for ahead it is being repaired. Kids play in the dirt piled up alongside a trench that has been opened down the middle of the street, peer in as an ancient sewer pipe is broken apart with a huge spike and a sledge hammer. It is Saturday afternoon, which explains (without recourse to a formal holiday) why everyone is so relaxed. The street becomes increasingly lined with shops, thereby confirming author’s intuition that he is headed in the right direction for return to the city center. But again he could be wrong. We head up Rue Ali Saleh.

Egyptians voted yesterday in a run-off presidential election that pitted an Islamist against Hosni Mubarak’s last premier, amid political chaos highlighted by uncertainty over the future role of the army. Voters braved the heat to cast their ballots.

The race has polarized the nation, dividing those who fear a return to the old regime under Mr. Shafik from others who want to keep religion out of politics and fear the Brotherhood would stifle personal freedoms. Police and army troops deployed nationwide.

(Jailan Zayan, “Voters ‘scared of both candidates,’” The Bangkok Post, June 17, 2012)

The seemingly irreversible warming trend of mid-afternoon turns suddenly chilly. The sun disappears behind a cloud. Author makes an educated guess. He turns down a street with automotive repair shops, hammer on metal audible. He has his eye on an avenue that the map cannot identify. In a large clock shop, hands on faces indicate every conceivable time of day. Stopping for directions again, author discovers that he is 90 per cent out of the maze but still is only 80 per cent of the way home. Within five more minutes, however, palm trees appear on the horizon, heralding, he hopes, the seashore.

“We are the spark that ignites the world; we know how to inflame,” said Ahmed Maher, 31, a leader of the April 6 Youth Movement, an early organizer. “But when we have a strong entity that can stand on its own feet, then we become but an alternative.”

Some said they almost welcomed the rise of Mr. Mubaraak’s former protégé, Mr. Shafik, because his return could help them rally the public once again. “When you think about it, the revolutionaries were never in power, so what kind of revolution is that?”

Many of the young leaders say that in those early days they were too afraid of appearing to take hold of power for themselves. Some say they were just intoxicated by their victory over Mubarak. “You could say that we just wanted to be happy,” one opined.

At another crossroads a brief conversation confirms his original intuition. We proceed down a grimier street, bordered by a wall in grey, by four-story factories. Three gorgeous women in their late 20s amble by, smiling so as to show off their white teeth and red lips. The wind whips up, blowing a wave of sand at author, who walks for a few paces with his eyelids closed. Can the sea be far away? Suddenly the street broadens and becomes a little bit cleaner. A black cat scavenges in a huge garbage bin. An institutional building is marked by signs in Arabic alone. The sound of late-afternoon prayers is here barely audible.

Now they say that they were manipulated by the military leaders. “We were duped. We met with the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces and they were very cute. They smiled and promised us many things and said, ‘You are our children; you did what we wanted to do for many years!’” Next week they offered the same smiles and promises.”

Others fault the Muslim Brotherhood, Egypt’s best-organized, 84-year-old, Islamist group. Before Mr. Mubarak’s ouster, it lent its full support to a united front, pushing for the presidential candidacy of the diplomat Mohamed ElBaradei, a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize and an inspiration and mentor to the young organizers.

During the revolt in Tahrir Square, the Brotherhood became a pillar of the protests, its leaders taking their cue from the young. But since Mr. Mubarak’s ouster, Brotherhood leaders have shown little interest in listening to the young or consulting with Mr. ElBaradei. Instead the Brotherhood began almost immediately to prepare for elections.

At the end of a broad, triangular square four palm trees are cordoned off with barbed wire. The neighborhoods are becoming increasingly residential. Outside a café is parked a truck, on whose side, “International Omo Excel,” the three words seriatim in white, purple and yellow. Ahead strides a woman with a large leather sack balanced on her head, her son at her back. A white van being boarded at curbside, forces author to step up onto the sidewalk. We have reached another roundabout. Presumably we can exit it in a direction that leads to author’s hotel. A man without a watch asks watchlesss author for the time.

“They betrayed us at the first corner and continue to betray us.” The resulting timetable killed any hope of unity against the military among those mobilized by revolt. “Even though not many of the revolutionary movements got into the Parliament, they were still affected by the polarization and accused each other of treason, even among the young.”

The Moon doesn’t rise in the west or the east, because Venus doesn’t have a Moon. It also has no measurable magnetic field. If you were to hike across Venus, you might as well throw your compass away, because it wouldn’t tell you which way was north. The lack of a magnetic field on Venus may be the key to why the planet is extremely dry.

Author in turn asks him for information but the Egyptian speaks no English and author, no Arabic. A younger man appears, however, to indicate the direction of our homeward course. At 4:00 o’clock grey skies have returned above a traffic circle’s high-rise apartment buildings. A girl walks by wearing a black shirt under a white sweater. Two black-clad policemen, having taken seats on a high curb to munch on biscuits, regard author’s recorder with suspicion. We pass the A. L. Borg Lab, then another building called La Résidence, the latter elaborately appointed with furniture designed to evoke antiquity.

Mr. Lofty, the Brotherhood’s former rising star, was expelled from the group and founded a political party, the Egyptian Current Party. It allied with the presidential campaign of the dissident Brotherhood leader Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotough, trying to combine an Islamist background with liberal positions on individual rights and social justice.

Mr. Lofty called their centrist project the best hope to defuse the polarization between Islamists and secularists, but most of the liberals or leftists that he had worked so closely with at the start shunned their efforts because of their Islamist roots. He said that he could no longer speak with the Coptic Christians because of their “difference in backgrounds.”

Down this avenue is a roundabout, at the center of which a brick arch with circular brick pillars. To one side, on a dirty cream wall, reads a sign for “Alex Eye Center,” The wind picks up, blowing sand into author’s eyes. Now seven schoolgirls, dressed in their blue uniforms, approach him together. Three stand on the sidewalk, four in the street. They cry to him, bless him, ask for his name. Reconfirming the correct direction, they bid him farewell. Soon we have returned to newly built brick walls, suggesting that we once again have entered the university precinct. Dormitories begin to rise behind the walls.

“Egyptian liberals are not real liberals,” said Mr. Lofty, accusing many former allies of “Islamophobia.” Others in their circle say that they still talk occasionally but cannot agree. Mr. Lofty and Mr. Aboul Fotouh “still come from the Brotherhood world,” said Shady el-Ghazali Harb, a liberal who voted for a Nasserite socialist in the first round.

He tried to avoid in this presidential race either an Islamist or Mr. Shafik. “We cannot have our choice between true Islamists and not-true Islamists,” said Mr. Ghazali Harb. He then joined others in pushing to boycott the election that is now in doubt altogether, hoping that the effort would give broader opposition to the Brotherhood and to the old elite.

Still we have a way to go, for nothing individually recognizable has appeared on the horizon. Author asks a man on the corner for directions, a cab driver who badly wants a fare. Author will be continuing on foot, he tells him. Turning the corner, we see a yellow-faced, green-shirted, red-panted Mickey Mouse, bearing the flag of Egypt in red-white-and-blue with a yellow crown. More schoolgirls crowd the sidewalk, loitering about a juice stand. We have reached yet another boulevard, one bordered by a low building, above which reads, in white letters on a blue ground, another company’s name, “Cairo Export and Import.”

The women often raised their hands to the sky in prayer to the immortals to grant a return, their hearts’ desire. “Aeson, ill-fated man! Surely better had it been for him, if he were lying beneath the earth, enveloped in his shroud.

“Would that the dark wave, when the maiden Helle perished, had overwhelmed Phrixus too with the ram; but the dire portent even sent forth a human voice, that it might cause to Alcimede sorrows and countless pains hereafter.”

We cross an alleyway in front of a building under construction. “A New Branch Soon,” reads a sign (for The National Bank of Egypt). Again, directions are sought, again from a crowd of schoolgirls, again happily given and received. Before long we reach another roundabout, at the center of which a large park with fountains at regular intervals, accompanied by Greek statues, or imitations thereof. This time we exit the circle with new instructions for a final turn. As we continue, a man in a bright red jacket is showing an address to another man in black, who is joined by yet another man in white shirt and pants.

All are arguing about contingencies. “Expert Data Computer Systems,” reads a sign, another, “Jotun: Mago Jet Multicolor Center.” We stroll past a Pizza Hut, a KFC, a Baskin and Robbins, side by side one another. We have entered an avenue bordered in large rubber plants and come upon a Bridgestone Tire sign. We pass the National Elevator Company, whose gold lettered sign announces it above a Toyota showroom. The neighborhood has become clearly upper-middle-class. Air-conditioners labeled “Power” adorn apartment balconies. A fruit stand across the street is three times the size of those seen earlier.

He was thirteen and in the eighth grade at Jefferson High School when he first made friends with Jeffry Isbell, who would become the catalyst that led to Axl singing in his first rock band. Born the same year, Izzy recalls how “we rode bikes, smoked pot, got into trouble — it was pretty Beavis and Butt-Head, actually.”

A computer center’s satellite dish is turned attentively skyward. We arrive at a distribution depot for Samsung electronics. After a blue metal gate for Delta Bus Company a McDonald’s looms into view, its golden arches riding above its Arabic name. “Concrete” reads an anthropomorphic sign in Greek letters; the word forming the chest of a figure whose head copies the head of Michelangelo’s David; “The Masculine Look” reads a legend at the level of its crotch. A graffito reads, “Tony’s birthday is on 12/2/99.” (We have already entered the 21st century.) A small sign shows, in stylization, the three Giza pyramids.

We reach the end of the bus yard. Again author makes inquiry and again is sent off with a set of complex directions, this time in Arabic. We come to another overpass, this one painted with a mural of the sea, on whose surface is the word “Mobilor,” in yellow. As we emerge into light, we encounter apartment towers of a dozen stories. Author follows the earlier leftward gesture of his director’s hand in hopes of success. Still, there is nothing familiar to be seen. The traffic, though, has begun to back up, as it had on our outward voyage. There is something in the air. We pass “Alexandria Marine Equipment Company.”

There’s no liquid water or ice on Venus, just concentrated sulfuric acid, which is present only high up in the clouds, and although there is a continual rain of the deadly liquid, the air is so hot that the drops of acid evaporate long before they can reach the ground. There are now only traces of water on Venus, but there probably was much more, even oceans of it.

Does this mean that the sea is near? Ahead strides a confident young Egyptian, “Wall Street” on the back of his jacket. Having overtaken him, author has second thoughts about his own direction and waits for the youth, who is lugging cartons of cigarettes, to catch up. The Egyptian pauses to respond to another inquiry by author, whom he turns gently toward the right. Beyond a sign that reads “Alenza,” “White Linen” has been lettered in black on pink. A man in a pink shirt with black-and-white stripes passes. Beginning to tire, author half considers the offer of a taxi driver, who instead points him homeward again.

A bus pauses alongside us, its occupants’ heads covered with white babushkas. On the sidewalk, in a purple burqa that reveals nothing of her face at all, a woman trudges homeward, a shopping bag on her arm. A driver whose car is out of gas uses a plastic water jug, its bottom cut out, to siphon fuel into his tank. Having managed, it seems, to transfer five liters or so of petrol, he starts up his engine again. We come to a filling station called “Miraco.” On the sidewalk is parked a white, four-door Mercedes 320SL. In black lipstick a dark woman smiles at author. A green sign behind her reads “Supermarket Select.”

“I will choose the one who will guarantee security and safety for our community,” said a Coptic Christian voter, from a polling station in the Shoubra neighborhood. “I don’t know how to feel,” said Nancy Abdel Moneim, outside a polling station in Manial.

“Original Cassette,” reads another. We have entered one of the more prosperous commercial districts of Alexandria, skirting a jeweler’s shop, a Mercedes Benz dealership, a men’s store. A man in wound-up gray turban (its ends dangling down his neck), dirty blue robe, stick in his hand, scowls at us. We pause at “Gag: Superstore,” a policeman in black jacket and white cap directing traffic out front of it. We pass a gaggle of dark-skinned middle-aged ladies standing at the entrance to a garage to discuss something in pleasant terms. One is in pink, one in beige, one in dark brown. We arrive at “Ted Lapidus.”

Its display window has been whitewashed, so that one cannot see in. Author reaches a divide in the road, where, still lost, he must again seek advice. This time a young Muslim not only points him in the right direction, he guides him, the new destination: the tram station, for author has wandered half-way back into town but failed to make one prescribed turn. Soon a number 5 tram arrives. Given the state of his Arabic, author must confirm that an upside-down V is in fact a 5. Having done so, his consultant places him in the custody of yet another man, who, with his nine-year-old son, is on their way home.

“I’m with the revolution, so I voted for Morsi . . . but frankly I’m scared of one and scared of the other, so I picked the one I’m least scared of.” The new president will step into office with no constitution and no parliament as yet in place.

After more assurances that we are on the way to San Stefano, author observes, on the beach, a crane dragging into position a boulder meant for the new jetty. It is a scene that he has viewed from his hotel window. He descends at the stop for San Stefano to stand across from familiar Pepsi Cola and Coca Cola signs, waiting to cross this avenue at last. “Mevhad,” reads the sign above a fashionable salon. A man in early middle age walks by, as if with palsy, his trembling hand bound up in gauze. Heavy traffic keeps preventing author from crossing the street. Finally he risks jaywalking to reach his hotel.

The air on Earth is mostly nitrogen and oxygen, with modest amounts of water vapor, carbon dioxide, and other gases. In contrast, the atmosphere on Venus is 96.5 per cent carbon dioxide and a few per cent nitrogen, with just trace amounts of everything else. The traces include oxygen and water vapor and various gasses that contain sulfur.

Axl found himself in the absurd situation of having to deny his own death. Slash complained to me that even MTV was getting in on the act. “They ran these pictures on the screen: ‘Axl — not dead.’ ‘Jimi Hendrix — dead.’”

Venus stays hot because the carbon dioxide, which holds in heat, maintains the greenhouse effect. Furthermore, in addition to normal carbon dioxide, the Venusian atmosphere contains an unusual form of carbon dioxide that is extremely rare on Earth. Normal carbon dioxide is a molecule that consists of one carbon atom and two oxygen,

“Then a picture of me and the band: ‘not dead.’ Then, ‘Jim Morrison — not dead.’ Then they showed a picture of Elvis — ‘dead’ with a question mark. It was a classic,” he scoffed. “I mean, when it comes to that, you can’t take it seriously.”

Back in his room he views a TV report on an Israeli bombing by Hezbollah in South Lebanon. An interview with the new king of Jordan is “coming soon.” Meanwhile, romantic soap operas dominate the Arabic channels. The Italian channel is showing models, in bare midriffs, skimpy brassieres and triangular panties, the French, a panel discussion of the Austrian neo-Nazi right.

Each oxygen atom contains eight protons and eight neutrons. The unusual carbon dioxide that is found on Venus is different in that one of its oxygen atoms has eight protons and ten neutrons. This so-called isotropic carbon dioxide is more effective at holding heat within the Venusian atmosphere than the ordinary gas that we have on Earth.

The one development Axl had no control over was entirely musical: the arrival of a new breed of rock band that, like punk before it, threatened to raze to the ground everything that immediately preceded it, including now lofty Guns N’ Roses.