The sun has arisen on the Upper Nile. Within fifteen hours we have passed from Alexandria to Edfu, author enjoying the luxury of a sleeping compartment with but one passenger (himself). In an hour we will be reaching Aswan. White birds have settled into the branches of date palms. Along the beige margin between two green fields a man in a long maroon robe leads a dignified white camel by a long slack rope. We glimpse a felucca’s white sail. The distance between railway track and river has momentarily widened. Three sunflowers stand at attention in a broad field, turning slowly toward the sun. We slow for a station whose name is marked only in Arabic. Desert-like mounds of sand encroach upon the tracks.

Tityrus, here you loll, your slim reed-pipe serenading

The woodland spirit beneath a spread of sheltering beech,

While I must leave my home place, the fields so dear to me.

I’m driven from my home place: but you can take it easy

In the shade and teach the woods to repeat “Fair Amaryllis.”

Egyptian polls declared Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood winner of the country’s first presidential race on Monday just hours after the ruling military council issued an interim constitution granting itself broad power over the government and all but eliminating the president’s authority in an apparent effort to guard against just such a victory.

In the interval between the dunes, we glimpse the road again, a sunlit blue truck hastening its way south, a yellow pickup heading north, its bed canopied in red, three white hearts surrounded by black. Under the glorious morning sun the surface of the asphalt road reads dark blue. Outside a town, two turbaned men, one in black, one in brown, sit in pink chairs at a suburban café. A goose struts past a humble dwelling, whose roof is painted white. Brown-clad junior high girls make their way up an alley toward a school. A red Toyota van hurries down the road. On a town’s outskirts we stop at a station, its name also in Arabic only. Above a wall behind it, edged in white, a magenta head bobs as it rides by on a donkey.

O Meliboeus, a god [Rome] has given me this ease —

One who will always be a god to me, whose altar

I’ll steep with the blood of tender lambs from my sheep-folds.

It’s by his grace, you see, that my cattle browse and I

Can play whatever tunes I like on this country reed-pipe.

(Vergil’s Eclogues, trans. C. Day Lewis [Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1963, 1983])

In July we were able to get it together to play what would become a legendary Chili Peppers gig. We got a job to headline the Kit Kat Club, which was a classic strip club that had been putting on rock shows. All four of us worked real hard to prepare for the show. At Hillel’s request, we even learned to cover Jimi Hendrix’s “Fire.”

A black-faced man in a baby-blue robe and sleek, white silk turban waits alone on a platform. Three Scania trailer-trucks pass us, the first two in yellow, filled with sand, the third in black, stacked with bags of cement. After an interval, a blue-cabbed, white-bedded truck arrives, a yellow back-hoe atop it. On the inner track, a grey, red-and-black-striped passenger train pauses before heading on downriver. As we leave the station, the back-hoe has already lined up with other construction vehicles to cross the tracks. At tables striped in yellow and red, four traditionally garbed men sip their tiny coffees beneath a satellite dish. At the border of a field, a farmer, having harvested two armfuls of greenery, takes a rest.

We got to the club that night, and they gave us a huge dressing room that must have normally been used by the strippers. I made sure that the lyrics were together, and then I wrote out the set list, which was a responsibility that I’d taken on early in the band’s life. We had an extra-special surprise that night.

As we head on out of town green fields of rice plants are sprinkled with golden wild flowers. We glance at a construction site, the workmen still huddled about a tent, two seated in red plastic chairs. A man in a pink over-garment kicks his legs against the ribs of a donkey, causing it to pick up the pace; it is pulling a flat-bedded cart with rubber automobile tires, behind which is tethered a second donkey. Four woolly brown sheep huddle against a wall, nuzzling each other. A tall tower, rising from a silver triangular base, gleams in the sun, its struts shaded. We come to a house in chrome yellow with magenta trim, pale blue doors and white shutters. On the front wall of another house is a carefully drawn airplane to Mecca.

Since we were playing at a strip club and the girls would be dancing onstage with us, we decided that the appropriate encore would be for us to come out naked, except for long athletic socks that we’d wear over our stuff. We had already been playing shirtless, and we realized the power and beauty of nudity onstage.

(Anthony Kiedis, with Larry Sloman, Scar Tissue [London: Sphere, 2006])

A dog scratches its ear, while two boys sit on a stoop brushing their teeth. A teacher stands proudly, resting his arm on the third-floor balustrade of a new school, the Egyptian flag fluttering behind him in the breeze. A man, a long stick in his hand, waits with a donkey for our train to go by. A woman clad in black velveteen, her sandals in orange plastic, has taken a seat to observe two cows, grazing. As we edge on through the outskirts of another town an advertisement reads, “Abu Simbel Macaroni.” A large orange stake-truck full of workers, who, sitting on its bed, squint to limit the effect of the rising sun, stops. Down alleyways, behind high grasses, we glimpse the banks of the river again. A tractor turns at the end of a field.

Well, I don’t grudge you that: but it does amaze me, when

Such a pack of troubles worries us countrymen everywhere.

On and on, sick-hearted, I drive my goats: look, this one

Can hardly move — in that hazel thicket she dropped her twin kids,

The hope of my flock, but she has to leave them upon bare flint.

The city men call Rome — in my ignorance I used to

Imagine it like the market town to which we shepherds

Have so often herded the weanlings of our flocks. Thus I came

To know how dogs resemble puppies, goats their kids,

And by that scale to compare large things with small.

The military’s charter was the latest of swift steps that the generals have taken to tighten their grasp on power just when they had promised to hand over to elected civilians the authority that they assumed on the ouster of Hosni Mubarak last year. Their charter grants them the power to control lawmaking, the national budget and declarations of war.

(David D. Kirkpatrick, “Generals in Egypt declare supremacy,” IHT, Tuesday, June 19, 2012)

Four grey blocks of new apartments stand out against the horizon, their windows shuttered attractively in various colors: turquoise, red and blue. We skirt a field of huge cabbages. A sign indicates the precincts of Nasr City; the silver smoke stacks of a factory rise above it. Furiously they are belching forth black smoke. Slowly we slide by the town’s central mosque, which culminates in a beautiful minaret, its crescent completed as a circle. Next door is a Coptic church, its two spires capped with three-dimensional crosses, their arms indicating the four cardinal directions. We are passing through Kom Ombu, Nasr City still off in the distance toward the East. A red Mazda stake-truck waits at trackside to cross.

But Rome carries her head as high above other cities

As cypresses tower over the tough wayfaring tree.

What was the grand cause of your setting eyes on Rome, then?

I’d come up with the idea of using socks, because back then I was living with Donde Bastone; he had a pot customer who developed a serious crush on me. She was cute, but I kept resisting her advances, which included sending me gag greeting cards with foldout rulers to measure the size of your dick, and even photos of herself blowing some sailors.

Its cargo of laborers is so large that they must stand cheek-by-jowl, packed in together. Along the side of a red brick building Arabic letters have been formed by inserting white bricks. We leave Kom Ombu behind as green fields, then blue-green verdure, then vegetable plots appear beside the tracks. Quickly we have entered another urban agglomeration. Instead of slowing, however, we pick up speed. Nonetheless, a white van, filled with a dozen passengers, whizzes past us. Having reached the outskirts of the town, we overtake the van. Beside an irrigation ditch a boy is setting out white plastic chairs before the yellow oilcloth-covered tables of a café. A pickup truck speeds by, piled with white crates of tomatoes and oranges.

One day she showed up to the house, and I decided to answer the door buck naked except for a sock wrapped around my dick and balls. Anyway, we were jazzed to play. Our interaction had gotten better and better. Before, our shows had been one big finale of fireworks from beginning to end; now we were developing different dynamics.

After dissolving the Brotherhood-led Parliament elected four months ago, and locking out its lawmakers, the generals on Sunday night also seized control of the process of writing a permanent constitution. The state news media reported that the generals had picked a 100-member panel to drain it. Hossam Bahgat made the following announcement:

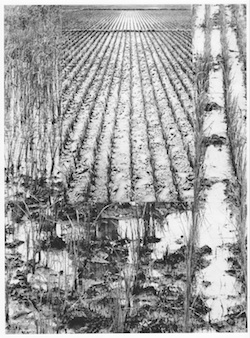

We in turn pass a coffee-colored Daihatsu truck, its bed empty. A small field of rubbish is burning beside the road, red flames licking upward. An official wall, high and spiked, surrounds a new transformer station, its corners surmounted with guard boxes made out of concrete. In an already harvested field, long rows of sheaves have been disposed in a northerly direction. Three old women dressed in black wait beneath a silver pole on which are strung five strands of telephone line. Suddenly we reach the banks of the Nile. A desert-like vista opens up. On the opposite bank, cliffs descend close to the water. The railway tracks here have been cut through rock. Under the dusty tops of palms, a village emerges.

Ten minutes before we were scheduled to play, someone broke out a joint. We had never smoked weed before a show, but we passed it around and took a hit, even Jack. As soon as the weed hit me, I became paranoid that all this hard work and this perfect feeling were about to be ruined by being stoned on pot, so I took a walk around the block.

“The new constitutional declaration completed Egypt’s official transformation into a military dictatorship.” The statement appeared as on-line commentary. Under the military’s charter, the president appeared to be reduced to a powerless figurehead. The Brotherhoood called the victory by the Islamist candidate, Mr. Morsi, a rebuke to the military.

Within a few minutes we have diverged from the river again. The scene to the eastern side of the train is markedly rugged. We exit a passage of dark green fields and the desert recommences. Villages, including their long walls, rise up the hills progressively. Their stuccoed building fronts are for the most part whitewashed, with an occasional pink, an occasional blue protruding into the general effect. Graffiti have given way to more stylized decorations. The cliffs rise quickly to tower above us, even at trackside. Then suddenly they disappear, replaced by a broad savannah. Before long, the hills have returned. We survey a larger village built upon many hills along the way, its walls dilapidated, some enclosing barren rocks.

Freedom gave me a look — oh, long-delayed it was,

And I apathetic; my beard fell whiter now as I clipped it —

Still, she gave me that look and late in the day she came,

After my Galatea had left me, when Amaryllis possessed

My heart. I had no chance of freedom, while Galatea reigned.

We had to follow a fantastic performance by an anarchistic outfit of eccentric masterminds called Roid Rogers and the Whirling Butt Cherries. But that only served to pump me up higher, ’cos I wanted to show everyone that we were strong. So we hit the stage and wailed. Jack and Flea were incredibly tight and Hillel was in another dimension.

We finished the set and ran backstage, and we were all in a frizzle tizzy. When we walked back onstage wearing only the socks, the crowd audibly gasped. We weren’t deterred for one moment by the collective state of shock that the audience was experiencing. We started rocking “Fire.” Our friend Alison Po Po meanwhile took swoops at my sock.

I was focused on the song and my performance, but another part of my brain started telling me how many inches I had between my sock and Alison’s farthest reach. As I watched a bunch of our friends who had all rushed the stage and were also grabbing for the socks, I suddenly had a totally liberating and empowering feeling.

I had no chance of freedom, no attention to spare for savings:

Many a fatted beast I took to sell in the temple

Many the rich cheeses I pressed for ungrateful townsfolk,

Yet never did I get home with much money in my pocket.

I used to wonder why Amaryllis called so sadly

Upon the gods, and let her apple crop go hang.

Tityrus was not there. The very springs and pine-trees

Called out, these very orchards were crying for you, my friend.

On the near side of the river, broad green fields illustrate the difference between desert and arable land. To the West again, two black birds fly above a cemetery. Its tombstones are small, primitive, widely spaced. We come upon a village built, like an American Indian pueblo, up against and into the cliffs. We ourselves have begun to climb quite quickly. At the outskirts of these villages we observe many deserted houses. We are approaching the environs of Aswan and will be there, the conductor tells author, in five minutes. The tracks begin to multiply, some filled with oil tanker cars, their cylinders dirty with age. Trackside activity increases. Our train slows. “Bank of Alexandria,” reads an advertisement.

You’re young and you’re not jaded yet and so the idea of being naked and playing this beautiful music with your best friends and generating so much energy and color and love in a moment of being nude is great. But you’re not only nude, you’ve also got this giant image of a phallus going for you. These were long socks.

What was I to do? There was no way out from my slavery.

Nowhere else could I find a divine one ready to help me.

Usually, when you’re playing, your dick goes into protection mode, so you’re not loose and relaxed and elongated, you’re more compact, like you’re in a boxing match. So to have this added appendage was a great feeling. But we never figured that the socks were eventually going to become an iconic image associated with us.

At Rome, Meliboeus, I saw that young prince* in whose honor

My altar shall smoke twelve times a year. At Rome I made

My petition to him, and he granted it readily, saying, “My lads,

Pasture your cattle, breed from your bulls, as you did of old.”

*Octavian

Mr. Morsi thanked God, who, he said, “guided Egypt to this straight path, the path of freedom and democracy.” He pledged to represent all Egyptians, including those who had voted against him. Other Brotherhood leaders had already begun escalating their defiance of the generals in meetings and statements Sunday night.

After conferring with General Sammi Hafez Enan, head of the council. the Brotherhood-affiliated speaker of the Parliament, Saad el-Katatni, declared that the military had no authority to dissolve the Parliament or to write a constitution. He said a separate 100-member panel picked by the Parliament would begin to meet within hours.

*

Fortunate old man! — so your acres will be yours still.

They’re broad enough for you, never mind if it’s stony soil . . .

But the rest of us must go from here and be dispersed —

To Scythia, bone-dry Africa, the chalky spate of the Oxus.

Once having debarked at the station, we mount quickly up a broad avenue in anticipation of reaching the Aswan Dam. A guard in black and orange armbands stands at the entrance to the bridge. “Coliseum” with a fan-like display of the colors of the rainbow, advertises photographic film and supplies. Once arrived upon the bridge we look down upon another display, a dusty group of palms with deciduous trees intermixed. Villages of blue and white houses are spread out along the river’s bank. The bridge, we read as we are already on it, is 1.5 km across. On its upstream side all is water; downstream, there is but a trickle. Way stations line the bridge. From this smaller dam we look upstream to the High Dam.

To this day both Tree and Flea claim they came up with “Red Hot Chili Peppers.” It’s a derivation of a classic old-school Americana blues or jazz name. There was Louis Armstrong with his Hot Five, and also other bands that had “Red Hot” this or “Chili” that. There was even an English band that was called Chilli Willi and the Red Hot Peppers.

Later they thought that we had stolen their name. But no one had ever been the Red Hot Chili Peppers, a name that would forever be a blessing and curse. If you think of Red Hot Chili Peppers in terms of a feeling, a sensation, or an energy, it makes perfect sense for our band, but if you think of it in terms of a vegetable, it has hokey connotations.

At the end of the lower bridge we finally arrive at the Nile, its flow rippled from here heading downstream. Red-epauletted soldiers in brown-olive uniforms wave us onward, past the personal villa of the President of Egypt. We mount farther through a forest of large electric towers onto a four-lane highway bordered with oleanders. As we pass military bases the sands begin yellowing to flaxen. Our driver indicates for us the direction of Libya. Before long we have reached the great temple, where author takes a stand before its imposing pharaohs. We have arrived at Abu Simbel and are about to enter its interior. Amidst tourist patter author views in awe the figures of colossal scale, a bas relief of a foreigner being slain.

There arose the prospect of assemblies that drafted competing versions of constitutions. Saad el-Hussainy, leader of the Brotherhood’s parliamentary bloc, said that their lawmakers would be at the Parliament Tuesday morning. The generals stationed military and riot police officers to keep the lawmakers out. This may lead to new clashes in the street.

There’s a restaurant chain named after the vegetable, and chili peppers have been merchandised of course in everything from home-decoration hangings to Christmas-tree ornaments. Suffice it to say that we were weirded out when people started bringing chili peppers to our shows as though in some kind of offering to us.

We have entered a side chapel, grotto-like in its ceiling, filled with votive statues performing their fealty to the gods. At the exit to this adjunct stands Isis, an ankh in her hand. A bat flutters past, escaping through the main portal. At the end, in the sanctum, sit figures more battered than elsewhere. The crowd of tourists proves too numerous for author to enter. He turns instead to face the light. Below lies Lake Nasser, a ship on its surface, the Egyptian flag waving at its stern. To visit this site we have travelled by 747 from Aswan 300 kilometers; then in a crowded bus; followed by a long walk downhill. The pilgrimage has been worth it. As author guards her luggage, a Japanese tourist, named Hiromi, enters the temple.

Ah, when shall I see my native land again? After long years,

Or never? — see the turf-dressed roof of my simple cottage

And wondering gaze at the ears of corn that were all my kingdom?

The military’s shutdown of the Parliament has turned the race into a life or death struggle for the Brotherhood, demoralizing Egypt’s Islamists and democrats alike and energizing Mr. Shafik’s supporters. The sudden possibility that the revolt that defined the Arab Spring could end in a restoration of military-backed autocracy captivates the region.

To think of some godless soldier owning my well-farmed fallow,

A foreigner reaping these crops! To such a pass has civil

Dissension brought us: for people like these we have sown our fields.

*

She has promised, when she returns, to speak to the question of the relationship between ancient Egyptian culture and modern Japanese. Author stands before second temple at Abu Simbel, some hundred meters away. Its portal is preternaturally small, the volume within likewise circumscribed, but perhaps more powerful in its imagery due to its slightness. Here the sanctum is available. It supports a single figure. The squarish pillars of the chamber surround primitive cat-like images. At the portal the guard holds an ankh with an eighteen-inch eye. From the courtyard of this second temple, the first is in full view, its immense figures humanized by the distance between us. Nature has dictated its heroic proportions.

In 457 BC, Herodotus had visited Egypt and traveled up the Nile as far as the first cataract, eager to discover whatever he could about the river’s origins. He would be largely disappointed. From a variety of Egyptian and Greek travelers, he learned that the river probably came from far to the west, from the country that we know as Chad.

Having emerged from her encounter with the pharaohs and their gods, Hiromi is ready to be interviewed. She begins with a statement: “This . . . temple . . . is . . . very big . . .” (We must use English, for author has no Japanese.) “. . . and . . . wonderful.” Author begs to differ: “If we compare it to the one at Luxor, this temple is not very big. (I agree that it is ‘wonderful.’)”

Hiromi concedes the point. “But Luxor temple . . . [long pause] “does not,” says author, “have the same form” [completing Hiromi’s thought]. “Yes,” she says. “What do you feel in these temples?” author inquires. [A long pause.] “Do you feel that the gods are there?” he elaborates. Hiromi responds with many “Hmmm”s. Finally author asks,

But no convincing detail was volunteered. On returning home, Herodotus wrote: “Not one writer of the Egyptians or the Libyans or the Hellenes who came to speak with me professed to know anything except the scribe of the sacred treasury of Athene at the city of Sais in Egypt. But this scribe made up for the vagueness of his other informants.”

“Which is better, ancient Egyptian or modern Japanese culture?” [Another long pause.] “A very . . . difficult question,” she says. Author presses on: “Tell me, which do you like better?” “Ummm,” says Hiromi surprisingly: “Like . . . Egyptian.” “Why?” says intrusive author, determined to reach some conclusion. “Ummm, long long time ago, many picture [sic] on the stone, . . . very very beautiful.” “Therefore, says author, this ancient civilization has beauty. What else does it have?” “Yes, picture is beauty and . . . ummm, . . . more story!” “Now ancient Egypt was a very great civilization, but so also is modern Japan,” says professorial author. “What do you like in modern Japan that is lacking in ancient Egypt?”

Sicilian Muse* I would try now a somewhat grander theme.

Shrubberies or meek tamarisks are not for all: but if it’s

Forests I sing, may the forests be worthy of a consul.

Ours is the crowning era foretold in prophecy:

*Theocritus

Between two mountains, he said, could be found “The fountains of the Nile, fountains which it is impossible to fathom: half the water runs northward into Egypt; half to the south.” Although Herodotus had sensed that the scribe did not seem to be in earnest, Livingstone believed he had been. This was because the scribe’s version tallied with others’.

But Hiromi will not commit herself. Having concluded what he regards as a satisfactory interview, author decides, later in the day, to repeat the process with a modern Egyptian, varying his question to read, “Which do you consider greater, ancient or modern Egyptian culture?” Having found a vigorous young Egyptian man named Nasser, he poses it. “Ancient or Modern Egypt?” he asks without missing a beat, “the same, no difference.” Since we are in the deep South of Egypt, author again raises the question of languages, with this more than adequate speaker of English. “Tell me, is Arabic your native language?” “No, Almanish,” he says. “And which other languages do you speak?” author inquires.

There was one difference. The scribe had mentioned two mountains between the four sources, whereas the Arabs had mentioned “a mound between them, the most remarkable in Africa. But, in Livingstone’s opinion, this difference seemed too small to worry about. A remarkable mound was likely to be a colossal feature: perhaps a range of mountains.

Born of Time, a great new cycle of centuries

Begins. Justice returns to earth, the Golden Age

Returns, and its first-born comes down from heaven above.

Look kindly, chaste Lucina, upon the infant’s birth.

“Español,” says Nasser. Seeking clarification, author inquires, “By Almanish you mean German, right?” “Yes, German,” says Nasser. “You are, then, a great scholar, says author, you speak German, Spanish (as we call it), Arabic and English.” “Yes,” says Nasser, laughing. “Let me shake your hand,” says author. “Now tell me something that you think my reader needs to know about Egypt. What should we all know about modern Egypt? What is important to you?” This question proves difficult, so author volunteers, “I notice that Egypt is very beautiful and the Egyptian people are very polite.” This seems to inspire Nasser. “In Abu Simbel, in Aswan, we have the Median people, not the Egyptian,” he corrects me.

Mountains near the northward-flowing sources delighted Livingstone for another reason. In about AD 150 the Greek astronomer and geographer, Claudius Ptolemaeus — Ptolemy, as he is known — had stated in his Geography that after marching for 25 days from Mombasa a traveler would arrive at “the snowy range whence the Nile draws its twin sources.”

Look kindly, chaste Lucina, upon this infant’s birth,

For with him shall hearts of iron cease, and hearts of gold

Inherit the whole earth — yes, Apollo reigns now.

And it’s while you, Pollio, are consul that this age shall dawn.

You at our head, mankind shall be freed from its age-long fear,

All stains of our past wickedness being cleansed away.

This child shall enter into the life of the gods, behold them

Walking with antique heroes, and himself be seen of them.

Egyptian election officials said Wednesday that they were postponing the announcement of a winner in last week’s presidential runoff, claiming that they needed more time to evaluate charges of electoral abuse that could affect who becomes the country’s next leader. The commission had been expected to confirm a winner on Thursday.

“In Luxor, in Cairo, there you have the Egyptian people.” “Now tell me about Nubian people,” author says. “Nubian people? I am Nubian people.” “And what are the Nubian people like, if you will be kind enough to tell me.” “Nasser points to his face, which is very black. [Great laughter all around.] “Ah, I see,” says author. You must recall that I am American, and in the United States we do not pay much attention to the color of someone’s skin.” But Nasser insists that he knows better: “American is for white, Nubian is for black.” “Tell me, in particular, about Nubian women.” “Nubian women, oh!” says Nasser, laughing, but he cannot articulate his thoughts. “Perhaps you mean that Nubian women are very beautiful.”

Based upon a public vote observed by the media, they were to have named Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood. The surprise delay instead intensified a power struggle between the Brotherhood and Egypt’s military rulers. It came just days after the generals who took over upon the ouster of Hosni Mubarak re-imposed martial law.

He will walk with heroes and rule a world made peaceful by his

Father’s virtuous acts. Child, your first birthday presents will come

From the wild — small presents: earth will shower you with romping

Ivy, foxgloves, bouquets of gipsy lilies and sweetly-smiling acanthus.

“Nubian, Nubian, very very beautiful, yeah, sure,” says Nasser, regaining his stride. “Now, are you married?” author inquires. “Yes,” says Nasser. “And how old were you when you married?” “Three,” says Nasser. “Ah, you have been married for three years, is that correct?” “Yes,” “And are you a happy man?” “Sure,” says Nasser. “Did your parents choose your wife for you?” “Oh yes, the family, oh yes.” “Perhaps this is why you are happy.” “Finally, what would you like to say to America, to Bill Clinton?” But the question does not inspire him, so author returns to a subject that Hiromi had spoken about, the small temple at Abu Simbel. “Why is the door so small?” “Because the Nubian people, you see, are very short.”

The drive downtown is an experience unto itself. You’re controlled by dark energy that’s about to take you to a place where you know you don’t belong at this stage in your life. You get on the 101 Freeway and it’s night and cool. It’s a pretty drive, and your heart is racing, your blood flowing through your veins, and it’s kind of dangerous.

Because the people who are dealing are cut-throat, and there are cops everywhere. It’s not your neck of the woods anymore; now you’re coming from a nice house in the hills, driving a convertible Camaro. So you get off at Alvarado and make a right. Here your senses go into this hyper-alert radar situation. Your mission is to buy these drugs.

Goats shall walk home their udders taut with milk, and nobody

Herding them: the ox will have no fear of the lion:

Silk-soft blossoms will grow from your very cradle to lap you.

But snakes will die, and so will fair-seeming poisonous plants.

Having moved across the plaza to the large temple, author is joined by a second Median, named Asher, to discuss with him and Nasser in situ the great monument. “It was built by Ramesses II,” is that correct?” “Yes,” says Asher. We turn next to discussing other temples in the larger southern vicinity. “Philae,” author proffers for the sake of information, is built on an island in the Nile.” “Philae and the Nile, all in Aswan,” says Asher. “Have you been on the boat that takes one to Philae?” “Yes.” “And how did the ancient Egyptians get there?” “Not the Egyptians, the Nubians,” author is again corrected. He takes out his map. “Here we are in Nubia,” he notes on the map. “What else should I visit?” “A Nubian village!”

They shut down the Brotherhood-led Parliament, issued an interim charter and slashed the president’s powers. They also took significant control over the writing of a new constitution. The new uncertainty about the presidential election results has only heightened the atmosphere of crisis and raised deep doubts about Egypt’s promised transition to democracy.

Although the vote count appeared to make Mr. Morsi the winner by a margin of nearly a million votes, his opponent, Ahmed Shafik, has also declared himself the winner. A former air force general, and Mr. Mubarak’s last prime minister, Mr. Shafik campaigned as a strongman who could keep the Islamists of the Brotherhood in check.

(David D. Kirkpatrick, The New York Times on-line, June 21, 2012)

Having accepted the invitation, author soon finds himself in the guide’s village of Abu Simbel, where we arrive by car. A blue dump truck, full of sand, blocks the middle of the road. The town is expanding; construction is everywhere underway. Nasser is driving, with Salas, whose car it is, sitting beside him. Libyan graffiti on walls along the way are pointed out. We stop and descend from the car. With great hospitality author is ushered into a house and offered a seat in its living room. The family is watching a television set, which is displaying images of the Sudan. Salas proudly points out that his family TV has Japanese and American channels too. Author is presented, for inspection, two beautiful Tabak, Libyan hats.

It’s a battle in which your life is going to depend on seeing everything around you, the guy on the corner, the undercover cops, the black-and-whites. You don’t want to commit any obvious traffic infractions, so you signal and make your left onto Third Street, cognizant the whole time of any cars behind you as well as in front of you.

You go two more blocks and start passing Mexican families, a couple of motels and a corner store; then there’s a grocery store on the left, which was the scene of many incidents in your life when you and Jennifer were together, when you used to shoot up in the car and throw up out the window. All these memories are flooding back.

Next he is given, for inspection, Nubian necklaces bearing images of camels engraved in ivory. Another is made of hematite; another has a scarab on the end of its string. “Very beautiful work,” says author. We return to what is available on TV. Author asks where the signal is coming from. “Sudan,” he is told, “from satellite.” Having read many news reports about the tragic country, he asks, “Do you think that Sudan today is a dangerous place?” “Not dangerous,” he is told. We are looking together at an Arabic channel. “For Saudians,” it is said. As Salas flips the channels to demonstrate the diversity of programming, we come to an Egyptian melodrama, then to the end of a soccer match in which Nigeria has just beaten Egypt.

Everywhere the commons will breathe of spice and incense.

But when you are old enough to read about famous men

And your father’s deeds, to comprehend what manhood means,

Then a slow flush of tender gold shall mantle the great plains.

Now shall honey sweat like dew from the hard bark of oaks.

Yet there’ll be lingering traces still of our primal error,

Prompting us to dare the seas in ships, to girdle

Our deities round with walls and break the soil with ploughshares.

On a news channel we watch a huge conflagration in an urban area, everyone in the room competing to offer commentary. It is Al-Jezeera’s Palestinian coverage. Having exhausted the collection of jewelry for sale and television programming, we jump into the double cab of a truck, Nasser, Asher, Salas and author, to tour the town, whose narrow streets are paved, whose building faces are constructed of mortared stone. We emerge out of an alley onto a gorgeous view of a reservoir. Goats are grazing at little tufts of grass along the roadside. As we return into the town, kids in a spacious square are at lively, improvised play with truck tires. We pass a temple, a grocery store; finally, we have a glimpse of the Nile.

There can be few historical events better known than the love affair between Mark Antony, triumvir of Rome, and the talented Cleopatra VII of Egypt. His association with her may not have been without political motives, for there was much to be gained by Rome fostering good relations with Egypt, the wealth of which was proverbial.

Ultimately, however, his relationship brought him into conflict with his astute, single-minded, brother-in-law, Octavian. The issue was finally settled at the battle of Actium, fought on September 31 BC, and a year later Octavian, who in 27 BC changed his name to Augustus, or August Emperor, entered Egypt for the first and last time.

(David Peacock, “The Roman Period,” in The History of Ancient Egypt (Oxford U.P., 2000)

As soon as you make a right onto Bonnie Brae, half a block up on the left, you see the dealers. They’re incredibly aggressive, and they watch every car that comes around the corner to determine if there’s someone to buy stuff. You either pull straight up on Bonnie Brae or you make a left onto the next side street, and they come swamping down on you.

“Sudan,” Asher tells author, is “up this way.” “It is 30 kilometer [sic].” In the nearby waters of the river, he says, are “real,” “big” crocodiles. “Two meter, three meter, ten meter.” “That’s a very big crocodile,” says author. “Yeah, ten meter long, for big one.” We traverse an enormous triangular plaza with the “Banque de Caire” at one end. We pass the Police Office. The sound of the call to prayers is in the air. This section of Abu Simbel is called “Kazimah,” Salas explains. Several kids on the street are trying to hitch a ride. We stop to allow them into the back of the truck. “Did you come to Aswan by plane?” Nasser inquires. “Yes,” says author, as we continue on, under blue skies streaked with the faintest of pink clouds.

A second Argo will carry her crew of chosen heroes,

A second Tiphys steer her. And wars — yes, even wars,

There’ll be; and great Achilles must sail for Troy again.

They’re in your passenger window, they’re in your back window, and you have to choose which madman you’re going to buy from. They are used to people buying 20 dollars’ worth, or 40, or maybe 60, but you pull out a wad of 100s and tell them you want 500 dollars’ worth. They can’t even keep 500 dollars’ worth of crack in their mouths.

At the end of a way paved in asphalt, edged with trees in arc-like topiary configurations, we stop at the Mairie, where author gains conversation with “the manager of the town of Abu Simbel,” who too rapidly pronounces his Arabic name. Author mentions that he has been talking with people in Aswan about the relation of modern and ancient Egypt and asks him, “What do you think Egypt will be like in the future?” “For the future history is making Egypt growing,” he says. “It is a big story.”This helps people here in Abu Simbel to be with the other people of the world, in the other countries.” “So you,” author comments, “are thinking, in economic terms, about the advantage of having tourists visit your great monuments.”

Egypt was a land apart — an exotic and distant part of the empire, more bizarre than any other province. Here pharaonic culture thrived and a visitor to Roman Egypt would have found himself in a time capsule, for the sights, sounds and customs of Roman Egypt would have had more in common with pharaonic civilization than with contemporary Rome.

Later, when the years have confirmed you in full manhood,

Traders will retire from the sea, from the pine-built vessels

They used for commerce: every land will be self-supporting.

They store the crack, like the balloons of heroin, under their tongues, so they start pooling their resources and come to you with a handful of saliva-covered crack. You make the deal and then you ask these guys, “Who’s got the Chiva?” and they point. Chiva is the dope. Then you head to another block and buy three, four or five balloons.

“In spiritual terms,” author muses, “when you see these 747s arriving, do you ever think that Ramesses II is still alive? Because he still has power to attract people.” “For myself I am very happy about it all, and yes, Ramesses is a very great name. He is a big man, on my side a great man, because he has a bow and is strong and has his wife.” “So we might say that people still worship Ramesses II?” “Yes.” “Because so many people are visiting you, and we have all spent much money to raise the temple.” “Yes, and people from all the countries are coming and buying the book to read about Ramesses, and taking pictures, so yes, as you say, he is still alive.” “So maybe ancient Egypt is a part of modern Egypt.” “Right.”

The whole time you’re trying to make the deal go down quick, because the cops could be there any second. By now you know where to get the pipes, and here you’re buying the little Brillo pads to use as screens in the pipes, all the techniques that you picked up from the street dealers. Then you roll up the windows and head home to get high.

Temples were still built in traditional style. The hieroglyphic script continued to be used, and Egyptian was spoken by the common people, although the lingua franca was Greek. Cleopatra was, as far as we know, the only Graeco-Roman ruler of Egypt to learn Egyptian, and then it was one of a multitude of languages in which she was proficient.

*

As we await an early flight from Abu Simbel back to Aswan, an airport book store owner is removing the heavy plastic curtain over his collection of materials about Abu Simbel. High above its shelves he has started a video. It recounts the story of the elevation of the two temples from their precarious position alongside the river to escape the modern flood, result of the construction of the Aswan High Dam. Workmen are shown hand-sawing blocks from the two temples; architects are shown seated about a round table, discussing the best way to proceed. Diagrams for the concrete dome to be constructed for the large temple to Ramesses II are displayed on the screen. Machinery of all sorts is shown in operation.

Further indications of the depth of the all-pervading pharaonic culture are the persistence of mummification as a burial rite and continuing reverence for the Egyptian gods. The special nature of Roman Egypt is undeniable, although there is a growing body of scholars who consider the “Romanity” of Egypt to be a more significant aspect of the subject.

Richard Burton believed that any man who succeeded in linking the mountains and river should justly be considered among the greatest benefactors of this age of geographical science. But he heeded the warning of the celebrated German explorer of the Sahara.

Heinrich Barth told him that “no prudent man would pledge himself to discover the Nile sources.” So Burton timidly redefined his mission as “ascertaining the limits of Tanganyika, the ethnography of its tribes, and the export of the produce of the African interior.”

It would be nine months before he discussed the source of the Nile again with Jack Speke, although both men knew very well that they would both be judged by how much they contributed to the solution of the world’s greatest geographical mystery.

The heads of Ramesses are lifted into their new positions. As the videotape proceeds, a crowd gradually assembles, stragglers from a French tour, joined by Germans commenting on the tape, Japanese tourists watching silently. A group of Swedes arrives, then Americans, until there is standing room only in the space before the bookstall. The effect of this rather ordinary, at least not extraordinary, videotape is mesmerizing. Something more profound than mere information is being purveyed. It continues to hold the attention of well-heeled retirees, of successful 55-year-old businessmen, from around the world. They all know the story but want to hear it again. So intent is their interest that they block the view of others.

The soil will need no harrowing, the vine no pruning-knife;

And the tough ploughman may at last unyoke his oxen.

We shall stop treating wool with artificial dyes.

For the ram himself in his pasture will change his fleece’s color,

Now to a charming purple, now to a saffron hue,

And grazing lambs will dress themselves in coats of scarlet.

As soon as you hit the pipe, boom, there’s that familiar instantaneous release of serotonin in the brain, a feeling that’s almost too good. You instantly start short-circuiting in your brain, because to get all that serotonin at once is so crazy and so intense that you’re liable to stand up and take off your clothes and go walking into the neighbor’s house.

Because you feel so good. And on one occasion I almost did do that. I came back to my beautiful, sweet, blessing-from-God home, up against this park, and I walked into the kitchen and took that first hit — and it’s always about the first hit; the other hits are all in vain, trying to recapture that first one — and I stuffed as much rock as I could in the pipe.

And as much smoke as I could in my lungs. I held it for as long as possible. Then I released the smoke. All that manic, psychotic energy came swirling around me again and I instantly became a different person. I was no longer in control of this person. I threw off my shirt, and it made perfect sense to go to my neighbor’s house with half my clothes off.

While Burton was confined to his tembe with fever, Speke — with Bombay interpreting — learned from the Arabs that there were three lakes, Nyasa, Ujiji and Victoria and not the single immense slug shown on the German missionaries’ map.

The natives called them Malawi (to the south), Tanganyika (to the west) and Ukerewe (to the north), which may be the largest of all. From the Ukerewe lake’s position, due south of the White Nile, Speke reckoned it was more likely to be the source of the Nile.

Like the story of the Taj Mahal, it has a second “text,” a backstory: the building of a temple to the wife of Ramesses. But it is mostly the authority, the serenity of the consummate art of the sculptors that conveys the spiritual power of the great king. This is what draws the audience in and holds its attention. Fourteen temples in all comprise the ensemble that was saved from the flood, but the major Ramesses temple and its pendant stand in a different relation to the rest of Egypt and its other monuments, much as the pyramids at Giza do. Even Osiris, even Isis, cannot compete with the appeal of this king. Over a 60-year reign he absorbed the gods into himself and wrote an epic in which he himself was the hero.

He created out of his person something heroic, something, like the gods, powerful and immortal.

*

Re-arrived in Aswan, author sets out to inspect the market: red pepper, white pepper, saffron; indigo, cumin, paprika; many varieties of incense. A little stall set apart from the others is offering cigarette lighter refills. “What is your name?” author asks its proprietor. “My name: Moussa,” he says. “Near Aswan,” says author, “on the island of Philae, there is a temple to Isis. Do you believe in Isis?” “Yes I believe Isis [sic].” “What do you believe? That she is very beautiful?” “Yeah, she is nice. I like my country.” “And Isis for you is your country?” “Yes. I am born in Cairo. I like the Nubian music. This is my country: Egypt: Cairo, Aswan, Luxor.” “So modern and ancient Egypt are the same.” “No different.”

Despite Egypt’s Romanization, cultural differences existed and it is hardly surprising that Rome adopted a somewhat hostile and suspicious attitude to the country. Roman senators were forbidden to enter Egypt and native Egyptians were excluded from the administration. It is significant that the only Egyptian town founded by Rome was Antinoopolis.

“Tell me, please, about Osiris.” “Ho-su-rees,” Moussa corrects author. “He is nice.” “Nice,” author repeats. “Yes,” says Moussa. “I read about this.” “Me too,” says author. Moussa: “Everyone say that if you look for Ho-su-rees, he have the magic eyes, and a white face.” “And in his story,” author adds, “he is born again, right?” “Yeah, very nice,” says Moussa. “Have you been to his temple in Abydos?” “No I don’t say this way.” “So how do you know Osiris?” “I read it in the book.” “You are a great scholar, Mr. Moussa,” author compliments him. “Thank you, thank you,” he replies. “Let me know if you ever need any help. For you, free! You are my cousin.” Author laughs, out of gratitude, and continues on.

The force behind this establishment was Hadrian, one of the few emperors ever to visit the country. His own love affair with Egypt is reflected in his great villa at Tivoli, where he attempted to create a Nilotic landscape in the Canopus garden. Despite Egypt’s unique aspect, it was to play a special role in our understanding of the Roman Empire as a whole.

A fruit seller is seated atop his cart, which he has already piled with oranges and bananas. Two Muslim girls in black scarves regard author; they wear black gloves as well. We have come to a display of Hookas made of green glass, of blue, of white, and of clear glass. We are on a major avenue, which also includes a café in two colors of green. Author, having decided that he has gone far enough, turns about, amidst the careful attention of many clients seated outside the café. As we return, the shops repeat themselves, in reverse order, along with ones not noticed before: hookah shop, butcher’s stall, incense store, paperback stall (filled with books in Arabic), spice store, whose fragrances are most noticeable this time by.

“Run, looms, and weave this future!” — thus have the Fates spoken,

In unison with the unshakeable intent of Destiny.

Come soon, dear child of the gods, Jupiter’s great viceroy!”

Author has taken a seat at an outdoor café, whose wooden tables are covered in orange oilcloth, strapped to their legs with elastic bands (against the wind). A Hyundai in electric lime-green weaves among donkey carts and motorcycles. Pedestrians pause before the butcher’s stall. Isis and Osiris, Amun and Horus, Anubis and Bastet are very much alive in this neighborhood. Two boys of eleven or twelve, who proposition author with an offer of “big banana in the butt,” must be shooed away. A threesome of soldiers, followed by a fourth, makes its way down the cobblestones, dressed in light khaki fatigues. Across the street two tourist shops sit cheek-by-jowl, one called “Roma Bazar,” the other “Paris Bazar.”

The title nesu-bit has often been translated as “King of Upper and Lower Egypt,” but it actually has a much more complex and significant meaning. The word nesu refers to the unchanging divine king (almost to the kingship itself), while the word bit describes the current ephemeral holder of the kingship; an individual king in power at a specific time.

At author’s café three men in white turbans sit before coffees in white cups, smoking. To one side, in a grey robe, an older man, white mustachioed, wearing brown street shoes, a long stick in his hand, sits next to a grey telephone, observing author. His expression is not very sympathetic. Now two younger men, in their early 20s, one in a blue, one in a grey robe, stop to converse with the seated men in white turbans. The two men shake the hands of all three seated men, then the hand of the grey-clad older man. After a farewell pause, the threesome continues along the street. A donkey cart pulls out into the flow of traffic, leaving behind it a blue Honda with orange-white-and-red racing stripes added by hand to its sides.

I knocked on the door, and she came out, and I said something like, “Did I leave my keys in there?” And she said, “No, I don’t think so, but let’s have a look.” I was ready to take off the rest of my clothes. She was kind and sweet, and, fortunately, I didn’t make too much of a scene. Three minutes later, that feeling evaporated and I realized I was half naked.

Each king, therefore, combined divine with mortal, nesu with bit, just as the living king was linked with Horus, and the dead kings, the royal ancestors, with Horus’ father Osiris. It was primarily because of the Egyptians’ sense of each of their kings as incarnations of Horus and Osiris that the tradition of the worship of divine royal ancestors developed.

(Ian Shaw, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt [Oxford: Oxford U.P, 2000])

Another man in grey goes through his wallet very slowly, counting the bills that it contains, as one of the three white-turbaned men seated at table together turns himself about, 180 degrees, to regard author. The Honda’s two rear-view mirrors, projecting out from the car six inches, show two scenes separated by 90 degrees, one, the facade of the café itself, the second, approaching pedestrian traffic. Having observed the owner of the café, a pencil behind his ear, change a four-pound note at the next table, author summons him and offers him a five-pound note. A white Fiat creeps slowly up the street. The owner gives author a one-pound note in change. A limping man in a cream-colored turban and white shawl arrives.

Once under way, on 18 January 1858, Burton’s “extremities began to burn as if exposed to a glowing fire” and he sensed death approaching. Later he recalled the horror of it: “The whole body was palsied, powerless, motionless; the limbs appeared to wither and die.”

He was unable to move his limbs for ten days, and it would be eleven months before he could walk unassisted. Until then he had to be carried by six slaves — eight when the path was difficult. Lake Tanganyika was 200 miles distant, a grueling ordeal, even on a litter.

At last on 13 February, after fording three small rivers, the caravan struggled through several miles of tall grass and then climbed a stony hill. As they reached the summit, Speke’s ailing donkey died under him. For two weeks he had been suffering from ophthalmia.

Come soon — the time is near — to begin your life illustrious!

Look how the round and ponderous globe bows to salute you

The lands, the stretching leagues of sea, the unplumbed sky!

The café’s owner offers author another one-pound note. Three women with large, heavy baskets of fruit on their heads, waddle by, one of them also holding a purse in the hand that steadies her basket. Only after author glances at the owner again does another note, a 50-piaster bill, make its appearance. A man goes by in the opposite direction, riding a donkey; a boy half his size holding on behind him. Author arises and departs, looking up at a sign that reads “Osiris Spices.” “Dante Bazar,” reads another, “Krum Stationery,” yet another, its window full of clocks for sale, picture frames, desk-top paraphernalia. High above reads an “Agfa” sign; on a corner stall, two more: “Coca-Cola” and “Daihatsu” (white, outlined in yellow).

*

First day, 1:30 pm, departure by boat from Aswan for Kom Ombo, on to Edfu, Esna and Luxor. Preceding us, The Nile Commodore, which had tied up alongside us, in fact had tied up to us, has cast off. Of the three boats tethered together, we are next. The white, four-deck, M.S. Da Vinci, a five-star cruise ship, heads north, occluding by its mass the palm-encumbered farther bank. Now, noisily, the Commodore turns around, it too preparing to set out. A white-hulled felucca, orange beneath its waterline, heads directly toward us, skippered by a helmsman in a pink robe. Causing his boat to come about, he continues to navigate by manipulating his sail, his rudder left free. The cabin’s radio on, author dozes off.

Both his eyes were inflamed and his vision so seriously impaired that he needed to be led when riding. Just behind him, Burton’s sweating carriers arrived at the top of the hill supporting their master in his machilla. Catching a streak of light, Burton asked what it was.

“I am of the opinion that it is the water,” replied the servant Bombay, unemotionally. After being carried a few yards more, Burton gained his first uninterrupted view of Lake Tangyanika. Fringed by “a ribbon of yellow sand [lay] an expanse of blue."

Its was the lightest, softest blue, in breadth varying from thirty to thirty-five miles and sprinkled by the crisp east wind with tiny crescents of snowy foam.” Beyond the lake rose the great “steel-colored mountains capped with their pearly mist.”

Look how the whole creation exults in the age to come!

At 2:00 o’clock sharp, our engines fire and our stern begins to drift toward mid-river as we too prepare to head downstream, leaving behind only The Symphony still moored at the dock. Now our engines reverse. The sun emerges from behind a cloud, whitening with its light the sails of the felucca; the wings of a river bird; the stucco fronts of houses; the sterns of larger cruise boats already underway. We are heading, first, upstream, presumably to make a U-turn about a very small island filled with rush-like grasses, in amongst which, on a sandy bank, three feluccas are nested, having pulled in next to a small ferry. A spit of sand connects the two halves of the island. At its south, a fishing dory has been turned upside down.

Speke was devastated that “the lovely lake could be seen by everybody but myself.”

Green plastic fishing nets hang from a pole to dry. Four more little boats, all their sails furled, increase the nautical population of the island, whose end we have reached. A black barge floats on downstream, thereby getting out of our way. We are about to make a turn and follow him, presumably outstripping the shallows before we attempt to. At last, a hundred meters beyond the island’s end, which is being skirted by a large blue skiff, we veer toward the channel. Confident that our boat is at last on course, we relax to view the western hills as the mid-afternoon sun suffuses them under chilly skies. The wind, though, starts up again, preventing author from audibly recording his words; he retires again to his cabin.

The gentle evocative landscape that surrounds Kom Ombo is the perfect background for the temple that stands on a small hill overhanging the Nile (the Arab word “kom” in fact means small mountain), almost a sort of Greek acropolis.

“Kom-Ombo-robu-juruwey, yaa salaam!” as a Nubian song has it (“To Kom Ombo, we are going, alas! [literally: O peace!]).” By 4:30 we have arrived within sight of the city. The Nile Symphony is pulling out from the wharf, as we pull in to dock alongside The Nile Plaza. We mount toward the temple, turning down a broad asphalt road. Between a high wall and low fields, a cow turns its head, listening to a noise from one of the boats. A year-old camel, still very small, stands on a threshing ground. Above the wall rise the lotus capitals of the Kom Ombo temple. Soldiers, one helmeted, all with their weapons drawn, protect the precious tourists, who are studying three remaining columns that orient its entrance.

While the stone differs from that of all other temples, because it was covered with sand for so long, the outstanding feature is the unusual, even unique, ground plan, the result of the unification of two adjacent sanctuaries dedicated to distinct divinities:

The outer court has been reduced to the stumps of a colonnade. Much is missing, though much remains. To one side of the precinct, above a baked mud wall, encroaching sands begin their ascent above, or their re-descent into, the temple. Apart from the chatter of guides, the court is remarkably quiet. In the declining sunlight author meanders through its passageways, bas reliefs still bearing traces of their once painted surfaces. Isis and Hathor stand relaxed before a pharaoh. A portico’s pillars are adorned with a large representation of Ma’at, a feather in her headband, an ankh in one hand, Bastet behind her. In a poignant piece of sculpture “The Roman-nosed figure of Hathor,” says the guidebook, “also represents Cleopatra.”

To the crocodile-headed Sobek, god of fertility and the creator of the world, and to Haroeris, or the ancient falcon-headed Horus, the solar war god. This is why the temple was called both “House of the Crocodile” and “Castle of the Falcon.”

(Giovanna Magi, A Journey on the Nile: The Temples of Nubia [Florence: Bonechi, 1995])

If but the closing days of a long life were prolonged for me,

And I with breath enough, the breath of Linus, to tell your story,

Oh then I should not be worsted at singing by Thracian Orpheus.

The temple of Kom Ombo stands at a double bend in the river; between us and the farther shore sits the Island of Truths. We descend to the bookstore, at the level of the fields, where the smell of manure is rank. Beneath two ancient Egyptian eyes, two young Arabic women are laughing decorously. At the margin of the river, the military guards are taking a break, seated about a charcoal fire to smoke. We have been looking at a Ptolemaic temple (136 BC), embellished in the Roman period; on this site, during the Middle Kingdom, another temple had stood, one to which Ramesses II had made additions, and before which Thutmosis II and Hatchepsut had erected gateways. Its forecourt was decorated by Tiberius.

Burton’s instructions had required him and Speke to reach Lake Tanganyika and then “to proceed northwards” to find out whether it might in some way be linked with the White Nile and the Mountains of the Moon. They strove to make decisive progress in this direction.

For even though Linus were backed by Calliope, the epic muse,

His mother, and Orpheus, by his father, beauteous Apollo, even

If Pan competed with me and Arcady deigned to judge us . . .

While they were at Ujiji, several informants electrified them with the news that “from the northern extremity of Tanganyika Lake issued a large river flowing northwards.” No Arab they had spoken to had actually seen the river himself and local Africans were ignorant.

Pan, great Pan, with Arcadian judges, would lose the contest.

But Speke had misunderstood Hamid, who had actually meant the reverse, that the Lake bore no relation to the Nile. “All my hopes,” confessed Burton, “were rudely dashed to the ground. Nonetheless, though Speke wished to see the river, Burton nixed the plan.

Night has fallen. Author peers out the cabin’s portal in our own boat, The Nile Legend, to watch as The Nile Commodore slowly leaves our flank behind, to join a procession of several other, even longer boats, whose lights illuminate the Island of Truths and its (likely) dangerous shoals. Before long we too are leaving Kom Ombo behind to head southward through a narrow passage before making our customary turn to enter the northward course of the channel, where two larger boats, The Nile Ritz and another, are passing one another, as the first heads south, the other north. A smog has settled in over the river. As we begin our turn, we look back through the mist at an even more mysterious Kom Ombo, its temple lit yellow.

Flickering flashes of tourist cameras add more complexity to its columns. We have negotiated our turn. The rose-pink streetlights on the avenue bordering the temple suffuse their glow into the smoggy ambiance, which is reflected onto the river’s surface. A tour ship, incoming from the north, shines a blinding beam at us by way of warning. The quality of light on the temple shifts in intensity and hue. Along with reflected light from the river, which forms a stage, white, off-white, yellow, pink and rosy glints create an indeterminate but somehow co-ordinated, cosmic dance that registers on the glass portals of the ship that we are leaving behind but can still see, even more clearly due to its increasing distance from us.

Although the “Court of the New Year” (to the north of the Kom Ombo temple’s last room) no longer exists, part of the ceiling of the “Pure Place” (where the statue was dressed for the Festival of the New Year), still remains, adorned with two images of Nut.

10:30 pm. We are regaled with a lively, not to say raucous, celebration in the dining hall honoring two recently married guests. The music is Nubian, its rhythm defined by intensely percussive drums, it melodic line by chanting voices. It is all accomplished by means of a male vigor, for there are no women employees on the boat.

On the body of the first representation of the sky-goddess are winged solar disks and, on the second, the different phases of the moon, while a barque of the night sails between the two. The pedestals that once supported the sacred barques can still be seen.

We retire from this lively scene to our cabins, only to awaken in the middle of the night, as we are arriving at Edfu, a crescent moon half obscured high above by the clouds. At bank-side a skyline of the city emerges in silhouette, as though provided for our view. Another tour boat, about to dock, is still waiting some distance offshore.

Access to the falcon-god Horus is from the back of the temple at Edfu. There has been a succession of structures built on this sacred site from prehistoric times (when the falcon-god was housed in a wicker hut) to the New Kingdom.

7:15 am approach to the precinct of Horus, up the quay, on whose steps are strewn plastic bags, orange peels and other touristic remains. We enter the early morning square of the city, on past its modern, mud-brick structures, to the temple’s entrance. At 7:30 the recently risen sun is bright, as we approach the complex, “one of the best-preserved in Egypt.” A pharaonic figure addresses the falcon-god on the first wall. We are about to enter the temple’s court, where the guidebook shows walls and columns filled with hieroglyphs, with figures supplicating the great god. We face the first pylon, on which Horus, brilliantly illuminated by direct sunlight, appears in nearly every configuration. We stand directly below him.

The temple owes its imposing appearance to Ptolemy III Euergetes who began to rebuild it completely in 237 BC. The work was not completed until 57 BC. Today visitors pass beneath the pylon and cross the court bordered on three sides by a colonnaded portico.

(Egypt [New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995])

Underneath a narrow lintel we now enter a tunnel into the court. Here the sun is even brighter. Taking umbrage in a convenient shadow, cast by a grey and blue building outside the temple, we stand some distance from the entrance to the temple’s pillared halls. The figures of two hawks in granite stand on either side of the opening. Nothing but blue sky is to be seen above the cornice. A small sphinx awaits us to at the entrance. Looking to either side of the present quadrangle, we count the twelve columns that border each, their corner pillars serving as the first, on either side, of a colonnade behind us, which numbers 10, giving 32 columns in all, plus the six rising from the top of the wall to the First Hypostyle Hall.

The custodians had an aviary no trace of which remains, where they raised falcons, one of which became the living symbol of Horus for twelve months, but the image of the god is omnipresent, magically, in the immobile granite statues guarding the temple.

We turn about to view the first pylon from within the court, as it rises in an increasingly powerful display. Horus, now without intermediaries, stands to either side of the high cornice connecting the two halves of the pylon. Horus, the Pharaoh, Isis, Amun-Re, Horus, the younger, nothing but a solar disk atop his head. Horus, Amun-Re, Isis, the Pharoah; Horus, another pharaonic figure, seated. Even the display itself of columns is overwhelming. On the western side the court receives light on all but four of its twelve columns. On the eastern side a metal scaffolding has been erected for repairs: orange, green, purple and turquoise buckets are displayed in four registers on the reddish structure.

The Roman emperor Domitian can be seen with various gods rendering homage to the triad Sobek, Hathor and Khonsu, together with a long text of 52 lines of hieroglyphs. The reliefs on the columns show the emperor Tiberius making offerings to the gods.

(Giovanna Magi, A Journey on the Nile: The Temples of Nubia [Florence: Bonechi, 1995])

As we leave The First Hypostyle Hall we view the second pylon, through which one enters the Second Hypostyle Hall. Here twelve columns have been disposed in a shallow chamber, which author circumambulates counterclockwise. The second pylon slants upward beyond the vertical entasis of the columns. The effect is irregular, beyond immediate comprehension. Hieroglyphs decorate the walls in half a dozen registers. Completing his circuit, author reorients himself at the center of the entranceway, looks upward to the capitals, and lets his eye fall upon an imposing figure, double winged, a solar disk atop his head. He steps forward processionally to enter another small chamber containing twelve columns.

This dozen is arranged three deep and four wide. From the Second Hypostyle Hall we enter upon a series of chapels, author inspecting first the one standing at 10:30 on the dial. All is intact. A cat; a maternal Isis; another image of her, with Hathor. The texts of the mysteries are long. We step into the chapel immediately south of the first to confront a more elaborate allegory: a procession of Nut and Thoth, who are joined by Horus. Crook and flail are here prominent. We enter a side-room at the northwest corner of the temple to view another magnificent display, then continue on to the chapel at 3:00 on the clock’s dial: an image of Horus with his back to Isis, two falcons communicating above an ankh.

When I commenced as poet, my Muse lived in the woods and

Dallied with pastoral verse. Next, kings and wars possessed me;

But Apollo tweaked me: “Tytyrus a countryman should be

Concerned to put flesh on his sheep and keep his poetry spare.”

The reaction of the audience was somewhere between shock and interest, “an amusement. People tended to laugh as much as applaud at key moments.” Elvis’ hands never stop moving, it looks as if he might be chewing gum, there was a twitchiness to his aspect — and yet there was a boundless confidence, too, as his mascara-ed visage scanned the audience.”

Shafik, the last prime minister under former Egyptian leader Hosni Mubarak, will be named the country’s new president Sunday, Ahram reported on its English version Friday, citing several unnamed government sources. Shafik will be declared victor with 50.7 per cent of the vote, the news outlet said. But the site’s Arabic version quoted election officials as saying that Morsi, the Muslim Brotherhood candidate, remained in the lead.

Isis and Horus appear in multiple representations, standing before human figures. Through an opening into a passageway that surrounds the chapels we observe the sky again, which has lightened to pale blue. It cuts into the temple in precise diagonals, illuminating half, leaving half in shadow. We return to experience the last chapel. Perhaps a mysterium of sorts, the guidebook calls it “the clothing cella”; it is darkened and ends in a stairway. With trepidation we descend to yet another chamber, down another stair. Horus, a double uraeus above his crown, stands with Nut, who appears beside the ram headed god of creation, in a joint supplication. We cross through the Offering Chamber into the Central Hall

Following Augustus’ settlement in the aftermath of the victory over Antonius and Cleopatra that made him sole ruler of the Roman world, provinces fell into two categories, senatorial and imperial. The former were ruled directly by the Senate, whereas the emperor governed the latter through legates by a grant of proconsular power that was periodically renewed by the Senate. The imperial provinces were the more important.

Since there’ll be bards in plenty desiring to rehearse

Varus’ fame and celebrate the sorrowful theme of warfare,

I take up a slim reed-pipe and a rural subject; if anyone

Falls in love with my poem, it is you, Varus, it will sing of.

On Saturday Elvis was back in Richmond with an Opry troupe. Among some who had already played dates with him was Mrs. Presley’s favorite country singing group. They were booked every night — in Greensboro, High Point and Raleigh, then in Spartanburg and Charlotte, with Saturday night off for Elvis to attend to business in New York City.

Here Hathor is leading the way for a pharaoh who brings with him offerings held high, one an image of the temple itself. We ourselves are standing opposite, so the guidebook tells us, “The Chapel of the God Min.” We observe a triplicate image of Bastet with triple cobras, one lion-headed, followed by double representations of monkeys, all culminating in the display of an ankh, tripled, sextupled. We face the final portal leading into what the guidebook tell us is “the Sacrarium.” Here a rectilinear alter is doubly surmounted by a double uraeus. The second cornice culminates in a pyramid. The altar is empty. Into the ceiling above have been cut three light shafts oriented vertically, north to south.

Nothing could charm Apollo more than a page inscribed to

Varus: Muses, begin! . . . Two boys, called Chromis and

Mnasyllus, came upon old Silenus lying asleep in a cave, his

Veins — as usual — swollen thick with yesterday’s drinking:

The administrative center of Egypt continued to be Alexandria, until it was displaced from that position in the fourth century by Constantinople. Two obelisks that Augustus had brought from Heliopolis provided a Roman touch. They stood before the temple of the deified Julius Caesar, known as the Caesarium, beside the Eastern Harbor. Long after Alexandria lapsed into insignificance they were known as Cleopatra’s Needles.

As thousands of Egyptian anti-government protesters packed the capital’s central Tahrir Square early Wednesday, Mohammed el-Baltagi retreated to his office in a quiet villa on Misr wel-Sudan Street. The Muslim Brotherhood’s general-secretary in Cairo gathered with young activists from other groups to plot the next moves in the current standoff against the country’s military-backed regime. This was a bit like old times.

(Matthew Kaminski, The Wall Street Journal, Friday-Sunday, June 22-24, 2012)

The next week they were back on the Hayride. They did “Heartbreak Hotel” for the first time, said Scotty, “and that damn auditorium almost exploded. I mean, it had been wild before, like playing down at your local camp, a home folks-type situation. But now it had turned into something else. That’s the earliest I can remember saying, What is going on?

We enter again into the large court for our exit from the temple through the first pylons. The columns, we now see, highlight images of Horus. Successively we view: Horus, Horus, Horus; Horus, Horus, Horus; Horus, Isis, Isis; the Pharaoh, the Pharaoh, the Pharaoh; the Pharaoh, the Pharaoh, the Pharaoh. We have reached a corner pillar, where, at eye level or slightly above, is a band of ankhs; a double crocodile; followed by ankh and double crocodile; ankh and double crocodile; ankh and double crocodile; ankh and double crocodile; ankh and double crocodile; ankh and double crocodile; double crocodile; ankh; double crocodile; ankh; double crocodile; ankh; double crocodile; ankh; double crocodile; ankh.

“It goes without saying,” says Mr. Baltagi, “that the military’s silly decisions” brought Egypt’s opposition back together. The support of secular, pro-democracy Egyptians helped swing last weekend’s presidential election to Mohammed Morsi,” he added. “This is news insofar as the Brotherhood rarely acknowledges political debts. According to aggregate poll tallies, Mr. Morsi beat the former Mubarak-era prime minister, Ahmed Shafik.

A more arcane though influential intellectual and literary development in Roman Alexandria was Hermeticism. The texts that became known as the Corpus Hermeticum were composed in the second and third centuries AD by Greeks in Egypt who wrote under the collective name Hermes Trismegistus. They identified the Greek god Hermes with the Egyptian Thoth and regarded him as the essential intelligence of the universe.

The garlands had slid from his head to the floor, and a wine jar

Dangled from the fingers that had worn its handle thin, creeping

Close — for Silenus had often teased them both with the hope of

A song — after which they tied him up in his own garlands.

On the inner walls of the first pylon, like the arrangement of Horus just reported on, a number of gods have had their images tripled. At the corner stands the Pharaoh before a hieroglyphic text. Crocodile and ankh have extended their arms to support pillars separating various texts that culminate in platforms, atop which stand the gods. We move to the final exit portal. Isis points in the Pharaoh’s direction as he marches across space and time, like Amun-Re. Above the courtyard before the first pylon the sun has illuminated the sky to another degree of paleness. A cock crows. It crows again. The January sky is utterly cloudless. At the edge of this space, the explanatory diagram and legend for the temple has been removed.

“Fetters? Why fetter me?” he cried. Enough to show that you can

Capture me. Now let me loose, lads.” Straight off, he began singing.

You could have seen the fauns and every wild thing caper in time to

His music, and the stiff oaks bow their heads — truly you could.

Ahmed Maher, a founder of the April 6 youth movement, held his nose and voted for Mr. Morsi. Tuesday night he joined the Islamists back in Tahrir Square.”We still believe there is a hope in the Muslim Brotherhood,” he says, without conviction. The Brotherhood, a hierarchical secret society founded in 1928, now promises to share power through a coalition government. Most of the blame for the still-born transition belongs with the military.

By the end of March the single had sold a million copies and “Blue Suede Shoes,” in an unprecedented achievement, was closing in on the top of all three charts: pop, country and rhythm and blues. Moreover the new album stood at nearly 300,000 sales, making it a sure bet to be RCA’s first million-dollar album. It had been titled simply Elvis Presley.

Before arriving at the temple, visit the mammisi or Birth House. A peristyle surrounds the vestibule flanked by two small rooms and a sanctuary; the pilaster capitals bear the heads of Bes, a birth divinity. The temple’s Coptic name means Place of Birth.

(Giovanna Magi, A Journey on the Nile: The Temples of Nubia [Florence: Bonechi, 1995])

We meander on, to a little shrine beyond the temple. Birds flitter out from its portals. A guard approaches to check author’s recorder (before detonating a potential bomb). We cross another threshold to confront yet another image of Horus. Retreating into the courtyard to seek shade from yet another solar disk, author approaches a wall atop which another, dark-olive-sweatered, light-olive-panted, guard stands. A crow caws twice. Author returns into the sun-lit space. The guard atop the wall coughs. A black-hooded woman in brilliant red dress mounts the narrow street, trailing behind her a young boy, her grandson. The sun continues to rise. In the shadows at the corner of the pylon stands a black-uniformed guard.

*

As we are pulling out of our berth at Edfu The African Queen, her white sides trimmed in red, pulls in alongside The Ninfea. Again we head upstream, before continuing downstream, lighting out toward the west bank in search of a channel deep enough for our draft. Once we have turned about, however, we skirt the east bank again, past Edfu’s minaret, past a hotel in dark green on lighter green, past another building in white and pale blue. Luxor is our final Nilotic destination, but we will stop at Esna on the way. A large Ferro-Alloy plant, coal piled at bankside, is disgorging black smoke. We gaze at idyllic landscapes; at flat, undistinguished landscapes; at villages above which single minarets rise toward the sun.