|

|

| Ikat | batik |

Pattern as Cosmology in Geometric Islamic Art: 3

Introduction

At the outset of our consideration of the Indonesian fabric arts known as Ikat and batik we require authoritative but economical definitions. Accordingly I have relied below on two erudite guides to Indonesia. I have edited all the passages taken therefrom, mostly abbreviating them for our present purposes. With many thanks to those who wrote the sentences on which mine are based and to those who published them. Throughout this presentation I have reduced paragraphs, conflated sentences and silently emended diction. Quotation marks for original texts so often changed would be inappropriate.

“Ikat Sumba,” edited from Indonesia Handbook (Chico, CA: Moon Publications, 1997)

Symmetry, but also imaginative juxtaposition

A definition of Ikat

Ikat is a very ancient tie-dye method of decorating rugs, shawls and blankets. Each fabric represents a colossal amount of human labor and only isolated, feudal, agricultural societies like Sumba’s still produce these hand-woven textiles. Although Ikat fabrics are also woven on nearby islands such as Flores and Roti, the craft here has reached an unusually high level. Woven from locally grown cotton, the cloths figure prominently in the ceremonial life of the island.

Uses for the fabric

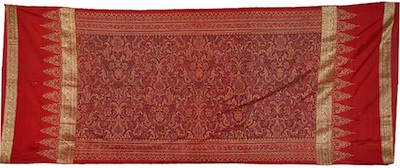

A single-piece blanket (selimut sumba)

Worn only by men, rectangular cloths called hinggi — with horizontal rows of human and animal motifs — come in pairs, one a shoulder cloth, one a wrap for the hips; they also serve as wall decorations or door curtains. There are also four classes of single-piece blankets (selimut sumba), which are traditionally used only in festivities or as burial shrouds. East Sumbarese sarung feature light figures on dark backgrounds. West Sumbarese Ikat are abstract.

The traditional colors

East Sumbanese sarung feature light figures on dark backgrounds. West Sumbanese Ikat are more abstract, with blue the dominant color. The age-old colors for hinggi are blue and white, or red and white and black. In East Sumba the rust color comes from the root of the kombu tree, dug up, chopped, and pounded into a pulp. Indigo is made from the tiny leaves of a low-growing indigo bush. In West Sumba the color from the blue indo plant (wora) is preferred.

Representational motifs

Designs differ greatly, but all reflect the life of the island. Motifs include tiny men on foot or armed on horseback, lions, stags, chickens, dogs, monkeys, birds, snakes, crocodiles, turtles, lizards, Chinese dragons, crayfish, crabs and octopuses. The outline of the Tree of Life is a recurring pattern. The skull tree motif dates from headhunting days, when captured heads were hung in celebration on the bare, blood-soaked limbs of a tree in the village center.

Though a comprehensive history of Indonesia would provide a much more detailed account of how Islam arrived and how it flourished in Indonesia, for our purposes the account given in The Lonely Planet guide, silently revised as usual, will have to suffice.

“The Spread of Islam,” edited from Indonesia, “History” (Melbourne: Lonely Planet, 2003)

The arrival of Islam in Indonesia

Islam first took hold in northern Sumatra, where traders from Gujarat in western India stopped en route to Malaku and China. Arab traders established posts in the latter part of the twelfth century. In 1292 Marco Polo noted that the inhabitants of the town of Perlak (now Aceh) on Sumatra’s northern tip had been converted to Islam. The first Muslim inscriptions found in Java date to the eleventh century. There may even have been Muslims in the Majahapit court.

The high point of Islam in Indonesia

Islam’s zenith was in the mid-fourteenth century. It was not, however, till the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries that Indonesian rulers turned to Islam, making it a state religion and super-imposing it on Hinduism and indigenous animist belief to form the hybrid religion of much of present-day Indonesia, especially of Java. By the time that the Majahapit court collapsed, many of its old satellite kingdoms had declared themselves independent Muslim states.

The traditional fabric, Ikat, is quite different from the modern fabric batik, already familiar to most foreigners, Asian as well as western, who have adapted it to their own purposes. For details of how it is used in Indonesia, we return to the Handbook:

“Batik,” edited from Indonesia Handbook (Chico, CA: Moon Publications, 1997)

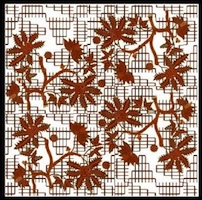

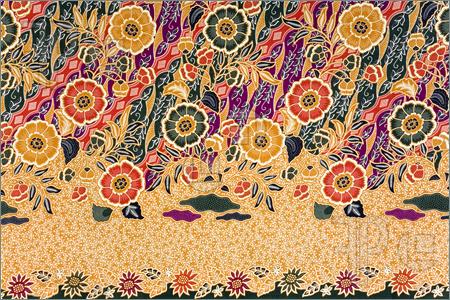

Regular ground and

irregular floral element

Traditional batik and modern dress

Java produces the world’s finest batik fabrics. Formerly they were used to make sarung, skirts, scarves and men’s headgear; nowadays they are used in housecoats, dresses, blouses, ties, belts, slippers, hats, umbrellas, sport coats, upholstery — anything that can be made of cloth. Most Javanese women cannot afford to wear traditional dress every day, but during holidays all women and girls wear the traditional sarung-kebaya outfit, the national women’s dress.

How the cloth is dyed

The prized batik designs, batik tulis, are drawn on fine cotton, linen or silk, first free-hand, in pencil. Then hot liquid wax, impervious to dye, is applied with a pen-like instrument called a canting, which has one, two or three spouts and a small bowl on top. Areas not slated for coloring are filled in with wax. The cloth is then passed through a vat of dye. The wax is removed with hot water. Next other areas are waxed over until the pattern is achieved.

Many different patterns

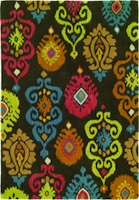

Repeated but irregular pattern

(Jogakarta)

Batik patterns are as various as Javanese society. You find crazy quilt patterns, circles, ovals, rosettes, stars, tendrils, checkered and round patterns, rhombuses, wavy lines, S-like flourishes, swastikas and bird tails. The introduction of Islam, which traditionally forbade the depiction of lifelike figures, led to stylized patterns without direct representation of human or animal forms. Chinese and European influences are evident in the design and color combinations.

Many different colors

Colors from organic dyes still differentiate regions: turkey red for Sumatra, blue-black for Indramayu, Jogyakarta browns, deep blues and maroon — colors of dignity. Mauve is suitable only for young, unmarried girls. West Javanese batik is punctuated by golden yellows and light browns with rich, dark blackish-blue backgrounds. In the northern coastal districts and on Madura, bright reds, yellows, glowing russets and greens are the dominant colors.

Pattern as Cosmology in Geometric Islamic Art: 3A

Matiebelle Gittinger, Splendid Symbols: Textiles and Tradition in Indonesia (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1990)

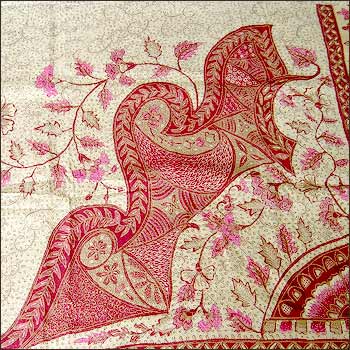

On pp. 118-119 of this reasonably comprehensive book, organized about the major islands, in a chapter called “Java” occur three black-and-white illustrations that I have not tried to reproduce, because even in the original text their details are hard to make out. Without having read Ms. Gittinger’s learned note, one might have overlooked that they all represent mountainous forms, according to her, depictions of the sacred Mount Meru, which, of course, in Indic culture is a symbol of the center of the cosmos, making them all cosmological designs.

Each of these textiles utilizes a similar mountain scene as its major composition. They are formed by small, undulating peaks that accumulate into larger mountain forms. . . . In all the compositions, a menagerie of birds and animals interlocked with plant forms fills the mountain scenery. The curling tendrils are called semen, from the Javanese word semi, relating to the budding or unfolding of leaves, and give to the whole the connotation of fertility and productivity. Initially interpreted as a sacred mountain scene or a rendering of the sacred Mount Meru, and later as a schematic rendering of the macrocosm, the cloths provide a rich design inventory sufficient for numerous mutually compatible interpretations.

Thus Gittinger somewhat lets us off the hook for our inattentive failure to recognize the sacred theme of these works. Her comment is of great interest, sentence by sentence: The design of these fabrics represents less “mountain scenes” than displaced and repetitive mountainous motifs. If we look carefully, they all have the five-peaked form of Mount Meru. As for the living “menagerie,” we have here what I call the “cosmographical” motif in Islamic patterned art. So the works are both cosmological and cosmographical, we might say.

Unlike the severe geometric art of classic Islamic design that we find in the Middle East, unlike even the looser forms of kashi in early Persian tile work, and the exacting architectural conceptions of the Indo-Islamic Mughal school, the Indonesian forms proliferate with fecundity, “fertility and productivity,” as Ms. Gittinger calls this feature. They are not only organic, as in kashi, but burgeoning, as, perhaps, befits a tropical culture. Leaves are everywhere unfolding, not just depicted in their ripeness. Here is a rich ambiguous mixture.

It is possible that the mountain scenery format was a standard visual statement for the general concept of sacred shrine area. This may have been intended to encompass four “historic” sacred areas, or to include the entire concept of religions domains set aside by the king for the maintenance of temples, ancestral shrines or religious orders of priests. . . . In records from the fourteenth century ships were symbols of Shivaite and Buddhist bishops, whereas particular species of trees represented the Royal family. At great celebrations, gifts were given in the form of mountains, ships, houses, or fish, which symbolized segments of society. Thus, though many of these figures are time-honored symbols, they can be read in a more limited way.

Irregular pattern for a man’s shirt

Pattern as Cosmology in Geometric Islamic Art: 3B

No less than the severe geometrical art of the Islamic Middle East, or the architecture of the Mughals, the patterned art of Indonesia is cosmological in design, perhaps even more fundamentally so. We turn now to two parts of an article by Peter Hobson and Paramita Abdurachman. It first appeared in Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 7, No. 3 (Summer 1973) and is titled “Some Observations on Indonesian Textiles.” The full text is available at the journal's website

Part (1): Excerpts (edited, as in the Appendix, for economy’s sake):

Macrocosm and Metacosm

A piece of woven cloth represents the fabric of the cosmos. The threads of the warp attached to the loom represents the immutable and predestined elements of Being; the threads of the weft, carried by the shuttle backwards and forwards across and between the threads of the warp, represent its contingent and variable elements. If the interweaving of a piece of cloth represents the Macrocosm, the point at which a single thread of the warp crosses a single thread of the weft represents the Metacosm, since the whole fabric is that point indefinitely repeated.

The process of cosmic creation

It follows from this symbolism that textiles in which designs are incorporated into the weave by a particular arrangement of the threads, and by dyeing the individual threads before weaving takes place, are a more complete reflection of the process of cosmic creation than those in which a design is later impressed upon the woven fabric. This type of manufacture, generically known as “Ikat weaving,” is in fact a more ancient and “primitive” art than that of the perhaps more familiar batik prints. There is, however, little Indonesian production of Ikat today.

Warp, weft and double Ikats

Three types can be distinguished: warp, weft and double Ikats. The first two have their designs dyed either in the warp or in the weft, before weaving; in double Ikats design and color are applied to the threads of both the warp and the weft so as to combine when woven into intricate patterns. There are also weaves in which the pattern is formed of intercrossing threads of various colors in simple stripes, or intercrossing stripes. Finally, there are many fabrics in which an ornamenting thread, often of silver or gold, is added by needle on the warp (Sungkit).

Male and female functions

There are metaphysical and psychological analogies between Ikat production and cosmic creation (in the Macrocosm) and between giving birth and creating new life (in the Microcosm). Spinning and weaving are envisaged as female functions, in Indonesia as elsewhere. On the other hand, men participate in the dyeing of the thread on the analogy of the process of human conception. Accordingly, the occasion of dyeing is always one of secrecy and privacy. The total process of Ikat production symbolizes and is sanctified by these creative concepts.

The sacralization of the secular

The sacred nature of this practice sanctifies the cloth when used for daily apparel; hence also the sacred aspect of the customs and taboos associated with it. In Indonesia these details differ from island to island, but in all areas not yet influenced by modern technology the arts of spinning, dyeing and weaving are accompanied by offerings, meditation and prayers, which are deemed essential for success. Incantations are carried out to ensure good results; when the threads are spun and pulled, incense is burned and religious offerings are made ceremoniously.

Pattern as Cosmology in Geometric Islamic Art: 3

Appendix

Part (2) of Peter Hobson and Paramita Abdurachman’s article (edited):

The various design motifs described below are now executed in many colors, but the batiks of Surakarta (Solo) and Jogjakarta in Java, now regarded as the twin “capitals” of batik and almost certainly the repositories of ancient traditions, rarely use colors other than dark brown, blue and white. The white is the “ground” on which the other two colors are placed, i.e., the “ether”; the blue and brown represent respectively “heaven” and “earth” or, in Hindu terminology, “Purusha” and “Prakriti,” the male and female principles. More ancient designs used only blue, which is the color of contemplation and divinity.

As in Ikat design, the motifs themselves can be conveniently divided into (a) the geometric and (b) the representational. The main geometric motifs include the following:

- Tjeplok: this is a cosmic symbol based on a central point from which radiate sometimes four and sometimes eight directions of space. The original term could well be Tjiptaloka, meaning “the created world,” though this is speculative. The geometric motifs combined within typical Tjeplok patterns are extremely varied and complex, consisting of squares, rhombs, circles, stars, etc., but the arrangement of the components around a central point from which they radiate outwards, in a form reminiscent of a mandala, is unmistakable even when these components take the form of plants, seeds, flowers and fruit-stones;

- Bandji: this is a swastika with the arms moving clockwise. The word “bandji,” taken from the Hokkiên dialect of Chinese, means simply “swastika.” It is, in fact, the fourth of the auspicious signs on the foot of Buddha, but it is considerably more ancient than Buddhism, being a world-wide symbol of the cosmos based on the directions of space;

- Ganggong: this is frequently regarded as a sub-category of Tjeplok, and indeed the spatial symbolism is identical. It is characterized however, by the fact that the directions of space are indicated not by separate shapes arranged, as in Tjeplok, around a central point, but as extension of the center drawn out into long coils like the stamen of a flower;

- Nitik: this is a variant of Tjeplok in which the design is picked out in dots (as the name Nitik, “dotting,” indicates), giving a fragile effect almost like a lace pattern. It is possible that Nitik started out by being actually worked into the weave of the cloth;

- Grinsin: this consists of small circles with dots inside, arranged rather like the scales of a fish. Since the circle is regarded, in all symbolism, as being the most perfect shape, complete in itself and having neither beginning nor end, it is a representation of that stage of Being which precedes spatial and directional manifestation. The central dot, or dots, represent latent, divine possibility. Before inscribing this pattern, the Batik maker is traditionally required to undergo a period of silent meditation;

- Kawung: this motif, consisting of touching or intersecting circles, larger than those found in Grinsing, and generally arranged around a central point in the manner of Tjeplok, is of great antiquity and, because of its particularly sacred nature, was forbidden in Jogjakarta to all but the members of the Sultan’s immediate family;

- Lereng: this is a generic name for a large category of designs moving diagonally across the cloth. It is thus quite separate from the cosmic and spatial motifs described above which are based, roughly, on the cross or the circle and run horizontally and vertically. The general significance of Lereng motifs appears to be that of specifically “human intervention” across the cosmic pattern. This is particularly true of the various Parang motifs, which form the most important sub-category of Lereng.

- Parang: this word appears to mean “sword” or “knife” or, again, possibly “war.” In appearance it resembles a line of slanting knife-like ornaments running across the cloth in diagonal stripes. If, as we have suggested, the designs based on elaboration of the circle or the directions of space are cosmological and have a “brahmanical” significance the Parang motif has a functional significance associated with the administrative and warrior classes, i.e., the Ksatriyas in Hindu-Javanese society. It is not surprising, therefore, that there is a large number of Parang motifs, many of which were traditionally restricted to the use of members of the highest court circles. The size of the Parang and its combination with other motifs vary to denote age and rank.

To turn now to the representational or non-geometric motifs, it would be quite impossible to attempt an exhaustive list, for they are innumerable and represent mostly natural objects, clouds, mountains, stars, water, plants and animals, often highly stylized and often arranged in the geometrical patterns referred to above. They thus form a natural complement to the metaphysical and spatial symbolism serving, as it were, to fill with mineral, vegetative and animal life the abstract worlds designated by the center, the circle, the directions of space, and heaven and earth. As such, the best and most ancient batik cloths, far from being simply beautiful designs to please the eye, are representations of the cosmos both as regards its celestial origin and its living content. If many display the vibrant and luxurient profusion which only a tropical landscape could inspire, others are marked by a more restrained elegance suggesting the sobriety of nature in which the principal design components are water, rain, rock or cloud patterns. The makers of batik recognize that all natural objects are, in the nature of things, symbols of a higher reality, and have used those objects in which this is most tangible as, for example, flowers whose petals form a spatial symbolism or seeds, which, when cut open, suggest the Grinsing referred to above.

The most frequent representational designs include the following:

- Semen: a dense profusion of leaves, birds, tendrils, seeds and half-open flowers; these are often combined with animals and insects frequently so stylized as to suggest plants rather than animate life, thereby emphasizing the intrinsic unity of the living world. They are frequently arranged in the Tjeplok pattern.

- Alam: a collection of plants, insects, birds and animals arranged fairly sparsely across the cloth. Alam means “the natural world.”

- Lar: a stylized representation of the wings of the mythical eagle Garuda, the King of Birds in Hindu mythology, and a symbol of divine revelation and creative force. Of the three variations, namely Lar proper (a single wing), Mirong (a pair of wings) and Sawat (two wings with extended tail feathers), the latter is traditionally reserved for the use of the highest nobility.

- Naga: a stylized serpent, snake or dragon, the symbol of divine energy;

- Siddha motifs: these all incorporate the lotus, a symbol of growth, purity and spiritual realization. Such motifs, featuring the lotus in various stages of growth, are used in specific designs, the half-open lotus for adolescents and the full-blown for people of rank;

- Merak: the peacock, symbol of beauty and nobility;

- Peksi or Sawunggaling: the phoenix, symbol of regeneration;

- Wadas: rocks;

- Megamendung: storm-clouds;

- Udan Liris: fine rain. This diagonal design (Lereng) seems to be apart from the others, but its inclusion in the Parang has made it a design reserved for the aristocracy;

- Mahameru: the sacred mountain;

- Segara: ocean life, including various kinds of fish and crustaceans, rocks and coral;

- Kapal: the ship;

- Singa-Barong: lions guarding the palace gates;

- Taman Arum Suniaraga: “The Perfumed Garden of the Soul at Rest,” a stylized garden pattern, probably of Islamic and Hindu inspiration, but also incorporating Chinese motifs such as buildings, tables and lamps within a context of vegetation and animals. The design has an unworldly and dreamlike quality caused by the extreme stylization of both the man-made objects and the animals, all which are transfused and transformed to resemble plants and rocks.

All the above motifs, both geometric and representational, are found in specific combinations in designs too numerous to mention, each having a specific name and each being considered appropriate for particular age-groups, ranks and occasions. One component however, which is frequently found in many designs of no particular hierarchical significance — frequently in Desa (village) cloth— is the Kepala, which means simply “frontal design.” This consists of a striking separate pattern in the center of the cloth arranged within an enclosed oblong running from the top to the bottom somewhat reminiscent of a barred-gate. The bars, drawn out in elongated triangles, Tunpals, are alternatively in light and dark colors. The dark sections frequently have small stars impressed on them and the light sections stylized birds, flowers and insects. They appear to represent the alternations of night and day, a symbolism reinforced by their being in facing groups of seven “day and night” sections. The older Kepalas were in sections of twelve or five. The former reflect Islamic symbolism, which has seven days in the week, and the latter reflects Hindu-Javanese time divisions; the temporal significance remained constant. The “gate” is frequently surrounded by stylized Naga designs and the rest of the cloth is usually of a luxuriant flower and plant pattern. The whole is therefore symbolic both of time, i.e., the alternations of day and night, and of space, filled with life, i.e., the world.