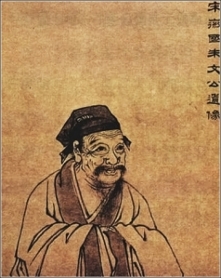

- Confucius and Confucianism

- The reception of Confucianism and Neo-Confucianism

- Korean history

- Korean literature

The Reception of Confucianism and Neo-Confucianism in Korea

[For this subject we turn to Keum Jang-tae, a professor in the Department of Religious studies at Seoul National University and “a leading scholar in the field of Confucianism” as it impinges upon Korean intellectual history. His Confucianism and Confucian Thoughts [sic] (2000) is admirably lucid and authoritative. I here adapt passages from Chapter 2, “Characteristics of Korean Confucianism.” As throughout my presentation of Confucianism, Neo-Confucianism and later developments in Korea and other East Asian cultures, I have silently emended quoted texts in the interests of economy and usefulness to the general reader.]

No exact date for the introduction of Chinese Confucianism into Korea can be given. It may, however, safely be assumed that Chinese culture with its Confucian element was introduced to Korea some time during the Warring States period in China (B.C. 403-221). During the Three Kingdoms Buddhism and Confucianism co-existed.

The civil service exam, introduced early in the Koryo dynasty, was based on Confucian texts. Many institutes for Confucian study were subsequently set up. An Hyang brought some writings of the celebrated Sung Neo-Confucian, Chu Hsi, from Yuan China to Korea; in 1305 Paek I-chong also brought works by the Ch’eng brothers.

During the early Choson dynasty Buddhist doctrine was criticized from the standpoint of Neo-Confucianism, most notably by Chong To-chou in his Against Mr. Buddha (1398). Sejong the Great, whose reign lasted from 1419 to 1450, ordered the construction of a royal academy by the name of Chipyonjon (Symposium of Wise Men).

Later a school of Confucian literati emerged to stress the practical morality of Tohak as the standard of a social ethic. Known as Sarim, the school was critical of bureaucrats, whom they saw as bent on personal advancement. They harassed the rival Hung’gu, a conservative faction, which led to four successive literati purges from 1498 to 1545.

The Confucianism of the Choson kingdom was not subservient to the power of the state, though the state remained its main protector. It served to check the state, many scholars sacrificing for the sake of upholding it as a guiding principle. Then in the 16th century Neo-Confucianism reached its height as philosophical speculation.

Scholars such as So Kyong-tik of Kaesong, Yi Hwang of Andong and Yi I of Seoul, joined to usher in a renewal of Confucian studies; their major concerns were the concept of the Great Ultimate, the theory of li-ki, the fundamental form of universal existence, and the structure of the innermost recesses of man’s mind.

Yi Hwang and Kim In-hu adopted a syncretic theory, contending that li and ki were basically the same. Yi Hwang (or “Toegye,” 1501-1572) emerged as one of the foremost Neo-Confucianists residing in the Southeast. Debates on the role of li and ki resulted in the growth of Yi Hwang’s dualistic theory and the monistic position of Yi I.

In the late Choson period, however, the relevance of Neo-Confucianism was called into question, leading to the rise of new approaches. Neo-Confucianism following Chu Hsi remained central but the Wang Yang-ming school, Western learning (Catholicism and scientific ideas from the West via China), and Practical Learning, shillak, emerged.

In defiance of the Neo-Confucian orthodoxy, early shillak scholars were receptive to new ideas from China. They turned to an experimental, pragmatic approach as embodied in Practical Learning for solutions to practical problems and criticized the obsession with moral considerations to the neglect of political, social and economic issues.

In the 18th century the Sangho School called Neo-Confucianism hollow and unrealistic. Chong Kay-yong (or “Tasan”) advocated sweeping social reforms and produced original commentaries on the Classics. Choe Han-ki (or “Hyegang”) in the early 19th century perceived ki to be the basic element of the universe.

He advocated an aggressive use of western science to reform the Confucian establishment. In that it concentrated primarily on the practical problems of daily life, shillak learning may be called secularized Confucianism. It sought to “materialize” the spirit of Confucianism in the real world. When Catholicism arrived in 1784, it was branded as a heresy.

The invasion of Kanghwa Island by a French flotilla in 1866 awakened the Choson court to western military might, plunging the hermit kingdom into commotion. As the consequence of an American man-of-war’s invasion of the same island 1871 and a show of force by the Japanese army in 1876 Choson government was required to open the nation to the world.

As for Confucianism in contemporary Korea, according to figures published by Songgyun’gwan and Yudhoe, its adherents in 1982 numbered 6,909,960, but an official census numbered them at 786,955. Few people, however, who embrace Confucian values consider themselves adherents of Confucianism as a religion. The young have fled the faith.