- East Asia’s “Post-Confucian” societies

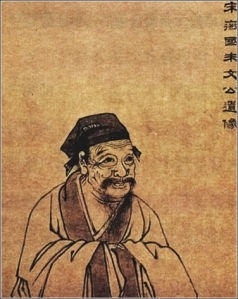

- Chu Hsi (Zhu Xi) emails

- MM as Confucian, Neo-Confucian and Post-Confucian

- Confucianism in 21st-century Chinese academic discourse

APPENDIX 1: Confucius and the Classic Texts

APPENDIX 2: Confucianism in early 20th-century China

Chu Hsi (Zhu Xi) emails

A.

I thought that non-Sinologist and Sinologist alike might be interested in an excerpt from an important work by Chu Hsi (I am using the Wade-Giles for a name spelled in pinyin Zhu Xi). The subject is Jen (in pinyin Ren, which more accurately reflects its Chinese pronunciation). “Jen” is also the word for “man” but here, with the symbol for “two” attached, it means “humanity,” the symbol for “two” indicating the relationships between men. Jen, often translated “Benevolence,” sometimes expanded to Jen Ai (the “Ai” meaning “love”), is one of the fundamental Confucian principals; in the later allegoresis of Confucius’ work it comes to mean, at its furthest reaches, Cosmic Love. Now for the opening of Chu Hsi’s medieval treatise on Jen (he begins by quoting Ch’eng Hao, one of his predecessors in Sung Neo-Confucianism):

“The mind of Heaven and Earth is to produce things.” In the production of man and things they receive the mind of Heaven and Earth as their mind. Therefore, with reference to the character of the mind, although it embraces and penetrates all and leaves nothing to be desired, nevertheless one word will cover it all, namely Jen. Let me explain fully.

The moral qualities of the mind of Heaven and Earth are four: origination, flourishing, advantage and firmness. And the principle of origination unites and controls them all. In their operation they constitute the course of the four seasons, and the vital force of spring permeates all. As a consequence, in the mind of man there are also four moral qualities — namely, jen, righteousness, propriety and wisdom.

Jen embraces them all. In their emanation and function, they constitute the feeling of love, respect, being right, and discrimination between right and wrong — and the feeling of commiseration pervades them all. Therefore in discussing the mind of Heaven and Earth, it is said, “Great is ch’ien (Heaven), the originator!” and “Great is k’un (Earth), the originator!” [Chu Hsi is quoting from the I Ching.]

Both the substance and the function of the four moral qualities are thus fully implied without enumerating them. [Mencius says,] “Jen is man’s mind.” Both the substance and function of the four moral qualities are thus fully presented without mentioning them. For jen as constituting the Way (Tao) consists of the fact that the mind of Heaven and Earth to produce things is already existent in its completeness.

After feelings are aroused, its function is infinite. If we can truly practice love and preserve it, then we have in it the spring of all virtues and the root of all good deeds. This is why in the teachings of the Confucian school the student is always urged to exert anxious and unceasing effort in the pursuit of jen. In the teachings [of Confucius, it is said], “Master oneself and return to propriety.”

This means that if we can overcome and eliminate selfishness and return to the Principle of Nature [T’ien-li, the Principle of Heaven], then the substance of this mind [i.e. Jen] will be present everywhere and in function will always be operative. It is also said, “Be respectful in private life, be serious in handling affairs, and be loyal in dealing with others.” These are also ways to preserve the mind.

Again it is said, “Be filial in serving parents,” “Be respectful in serving elder brothers,” and “Be loving in dealing with all things.”

And so on. One can see that Chu Hsi is not at all obsessed with ontology, epistemology, metaphysics and systematic argument in the western senses of those terms.

B.

[I am seeking help in determining the nature of Chu Hsi’s “monism,” such as it is.]

Chu Hsi, we have been told, is a great synthesizer himself, but he excludes as well as includes, for he seems to be not so much synthesizing Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism as redefining Confucianism, excluding Buddhism, and drawing upon Lao Tzu.

It would take years to learn what one would need to know about his reading, of Lao Tzu, of Mo Tzu, of the Yin-Yang school, of the Legalists, of Tung Chung-shu, and even of what is called Taoistic Confucianism, to say nothing of Chu Hsi’s immediate predecessors.

So I must take short cuts. I am inviting you again to look at texts by Chu Hsi himself (or excerpts therefrom) and comment on them. I continue now with various passages, interspersed with glosses by Wing-tsit Chan, and a kind of imperfect directing hand of my own.

*

Confucius says, “Sacrifice life to realize Jen.” “This means,” in Chu Hsi’s gloss, “that we desire something more than life and hate something more than death, so as not to injure this mind. What mind is it? In Heaven and Earth it is the mind to produce things infinitely.”

Of this mind, Chu Hsi says, “In man it is the mind to love people gently and benefit things. It includes the four virtues (humanity, righteousness, propriety and wisdom); it penetrates the Four Beginnings (commiseration, shame, deference, right and wrong).

“Someone said (after Master Ch’eng) that love is not Jen, and that he regarded instead ‘the unity of all things and the self’ as the substance of Jen.”

Chu Hsi answered: “From what they call the unity of all things and the self it can be seen that Jen involves love for all, but unity is not the reality that makes Jen a substance.”

[I am looking in Chu Hsi for an expression of “The mind of Heaven and Earth,” “The Mind of Man” and their interpenetration as an equivalent of Kantian Erfahrung, as a sort of Chinese “Experience,” that that I may better understand Chinese literati painting.

Chu Hsi, however, from a western point of view, is doing several unexpected things: by insisting, first, that everything be keyed to Jen; second, that philosophy be “moral,” and, third, that we be wary of any interpenetration of the Mind of Nature and the Mind of Man.]

He turns again to the above quotation: “From what they call the unity of all things and the self, it can be seen that Jen involves love for all, but unity is not the reality that makes Jen a substance. . . . Furthermore,” he says, “to talk about Jen in general terms of the unity of things and the self will lead people to be vague, confused, neglectful, and insufficiently alert. The bad effect — and there has been a bad effect — may be to consider things as one’s self.”

In other words: Jen consists of both substance (or “nature” — including man’s nature) and function (“love,” including the love of nature). Moreover, in Chu Hsi “Jen seems always to be supplemented by “I,” or righteousness (yi in pinyin).

Chan says, “Since Jen is the character of the mind, it is in the nature of every man therefore a universal nature. Thus it includes Confucian wisdom, propriety and righteousness.” So much, then, for pure “nature,” which, we might say, only exists in the mind of God.

Here Chan offers a selection from Chu Hsi’s Treatise on Ch’eng Ming-tao’s “Discourse on the Nature [sic]”: “‘What is inborn is called nature’ [Ch’eng Hao], i.e., “What is imparted by Heaven (Nature) to all things is destiny.

“What is received by all things [wan wu] from Heaven is called nature. . . . Man’s nature and destiny [ming, mandate, fate] exist before physical form [and are without it (Chan)], while material force exists after physical form [and is without it].” We return to Master Ch’eng:

“One’s nature is the same as material force, and material force is the same as nature.” After working over this idea Chu concludes: “For there is nothing in the world that is outside one’s nature. . . . What is inborn is called one’s nature. Nature is simply nature.

“How can it be described in words? Those who excel in talking about nature only do so in terms of its emanation and its manifestation. Nature may be understood in silence, as when Mencius speaks of the Four Beginnings [humanity, righteousness, propriety and wisdom].

“By observing the fact that water necessarily flows downward, we know that the nature of water is to go downward. Similarly, by observing the fact that the emanation of nature is always good,” Chu His says in conclusion, “we know that nature involves goodness.”

I presume to make the following generalizations:

(1) There is always a moral element in Chu Hsi’s conception of “nature” and (2) At least in his own representation of the concept, it is always fundamentally good. (3) Despite change and/or degeneration, “the nature” of which he speaks is a constant.

Finally, Wing-tsit Chan’s vastly more learned gloss:

“In this essay, Chu Hsi not only removes the ambiguity in Ch’eng Hao’s original treatise, which uses the same term (“nature”) for basic nature — which is perfectly good — in the first part, and for physical nature — which is both good and evil — in the second.

“He also harmonizes all philosophical theories of human nature before him, whether Mencius’s theory of original goodness, Hsün-tzu’s theory of original evil, or Chang Tsai’s theory of physical nature.

“Evil is now explained, and in Chu Hsi the key Confucian teaching that evil can be overcome is re-affirmed.”

C.

1. There follow several quotations from a work of Chu Hsi’s titled “The Relation between the Nature of Man and Things and Their Destiny”:

About the distinction between Heaven (Nature), destiny (ming, fate), nature, and principle: Heaven refers to what is self-existent; destiny refers to that which operates and is endowed in all things; nature refers to the total substance. . . ; and principle refers to those laws underlying all things and events. Taken together:

Heaven is principle, destiny is nature, and nature is principle.

2. Shortly thereafter Chu Hsi says in summation:

Principle is the substance of Heaven, whereas destiny is the function of principle. One’s nature is what is endowed in man. And one’s feelings are the function of one’s nature.

3. On being asked about Chang Tsai’s comment that moral character fails to overcome material force, Chu Hsi replies:

Master Chang Tsai merely said that both man’s nature and material force flow down from above. If my moral character is not adequate to overcome material force, then there is nothing to do but submit to material force as endowed by Heaven. If my moral character is adequate to overcome material force, however, then what I receive from the endowment is all moral character. Therefore if I investigate principle to the utmost and fully develop my nature, then what I have received is wholly Heaven’s moral character, and what Heaven has endowed in me is wholly Heaven’s principle.

4. At the outset of an essay titled “Moral Cultivation”:

Although literature cannot be abolished, nevertheless the cultivation of the essential and the examination of the difference between the Principle of Nature and human selfish desires are things that must not be interrupted for a single moment in the course of our daily activities and movement and rest.

5. Chu Hsi quotes “Master Ch’eng” approvingly:

“One must not allow the myriad things in the world to disturb him. When the self is established, one will naturally understand the myriad things.”

At the end of this essay, “Moral Cultivation” (which includes sections titled “How to Study,” “Preserving the Mind and Nourishing the Nature,” “Holding Fast to Seriousness”) Wing-tsit Chan comments:

“Like Ch’eng I, Chu Hsi struck a balance between seriousness and the investigation of things in moral cultivation. . . . His own contribution in this regard is to have steered the doctrine away from the subjective emphasis in Ch’eng Hao toward a unity of internal and external life.”

6. Under the heading “Extension of Knowledge,” Chu Hsi says:

What sages and worthies call extensive learning means to study everything. From the most essential and most fundamental about oneself to every single thing or affair in the world, even the meaning of one word or half a word, everything should be investigated to the utmost and none of it is unworthy of attention. Ch’i-yuan asked: “In investigating the principles of things and affairs to the utmost, should one investigate exhaustively the point where all principles converge?” [Chu Hsi’s] Answer: There is no need to talk about the converging point. All that is before our eyes is things and affairs. Just investigate one item after another somehow, until the utmost is reached. As more is done, one will naturally achieve a far and wide penetration. That which serves as the converging point is the mind.

Wing-tsit Chan comments:

“The philosophical basis for all these sayings on the investigation of things and the extension of knowledge is that principle is universal. . . . One major difference between Ch’eng I and Chu Hsi is that while Ch’eng largely confined investigation to the mundane world, Chu extended it to cover the whole universe. . . . The whole spirit of the Ch’eng-Chu doctrine, involving both induction and deduction, is consonant with science.”

D.

Two emails ago I said that I was looking in Chu Hsi for an expression of “The mind of Heaven and Earth,” “The Mind of Man” and his view of their interpenetration as a sort of Chinese “Experience.” I have very nearly found this in Yung Sik Kim’s The Natural Philosophy of Chu Hsi (1130-1200) (Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society, 2000), Chapter 2, “Li and Ke-wu (Investigation of Things),” 21:

“[Chu] spoke of natural objects and phenomena,” says Kim, “to illustrate ke-wu . . . rhetorically; rarely was he thinking of actual investigations or analyses of the objects and phenomena. In fact, the mind’s reaching the li of things was for him a kind of ‘resonance’ between the mind’s li and the things’ li. This was so because the heavenly li resides both in man’s mind and in things and events. And since the many individual li of things and events are but manifestations of the one li, Chu Hsi could say that man’s mind in its original state contains all ‘the myriad li.’ He even went on to equate the li in the mind and the li in things and events:

The li in things and in my mind are originally one thing. The two do not have even a small gap [between them]. But it is necessary that I respond to them [the li in things]. Things and the mind share this li.”

Meanwhile, in a Chinese-language study that I found in Bangkok I have identified what may serve as the single quotation that I was hoping to place in relation to Kant’s “In der Erfahrung ist die Wahrheit.” The book is a commentary on selected quotations from Chu Hsi, one of which, in the first chapter, reads [in pinyin transliteration]:

Yi(1) Chuan(1) yue(1): Zai(4) wu(4) wei(4) li(3) chu(4) wu(4) wei(4) yi(4).

I would much appreciate an expert, anonymous translation, including the final term, which presumably is what scholars are translating as “mind” or “Mind.” Further elucidation of what we have here would be helpful, including comment on the degree to which Chu Hsi’s thought approaches and differs from Kant’s.

E.

Chang Tsai, in a famous inscription known as the Hsi Ming or “Western Inscription” (because the piece of calligraphy hung on the western wall of his study), says that, since all things in the universe are constituted of one and the same Ch’i (here meaning “substance”), therefore all men and other things are but part of one great body. He elaborates:

“If, for instance one loves other men simply because they are members of the same society, as one’s own, then one is doing his social duty and is serving society. But if one loves them also because they are children of the universal parents, then by loving them one not only serves society but at the same time serves the parents of the universe.

“The passage concludes [in Fung Yu-lan’s paraphrase] with the saying, ‘In life I follow and serve [the universal parents], and when death comes, I rest.’”

*

Neo-Confucianism before Chu Hsi had two separate schools initiated by two brothers, the Ch’eng Masters. Ch’eng I (1033-1108), the younger brother, initiated a school completed by Chu Hsi (1130-1200) known as the Ch’eng-Chu school, or Li Hsueh (School of Principles). Ch’eng Hao (1030-1085), the elder brother, initiated another school continued by Lu Chiu-yuan (1139-1193) and completed by Wang Shou-jen (1473-1529), known as the Lu-Wang school or Hsin Hsueh (School of Mind). Fung says:

“The main issue between the two groups was one of fundamental philosophical importance. In western philosophical terms, it was a question of whether the laws of nature are or are not legislated by the mind or Mind. That was the issue between Platonic Realism and Kantian Idealism, and may be said to be the issue in metaphysics.”*

In terms of my HERA sequence, whose trilogy All, Regarding, Exists describes the landscapes of Arizona, New Mexico and Oklahoma (taking as their model Chinese literati landscape types), I note that Chu Hsi and Chinese landscape painting are more like American than European Experience: vast vistas organized by unified philosophies in Sung China and Enlightenment America, the results of a universal Tao Hsueh (Neo-Confucianism) and the general democratic theories of Montesquieu, Paine and the Founding Fathers.

The American Presidents at Mount Rushmore are embodied in Mother Earth (a mountain). Are Yao, Shun, the Duke of Chou and Confucius embodied in Chinese landscape painting? See an earlier email (whose text I paste in below), occasioned by my reading this season of J.J. Wargo’s The Logic of Nothingness: A Study of Nishida Kitaro (Hawai’i, 2005):

The HERA sequence, which I have schematized a dozen times, has finally come into focus as a result of Robert J.J. Wargo’s Logic of Nothingness, a study of Nishida Kitaro, the leading figure, it seems, in the early twentieth-century “School of Kyoto.”

Two sets of Nishida's categories (plus my landscape models):

| Exists | the intelligible world | absolute nothingness | (Yuan landscape) |

| Regarding | the world of consciousness | relative nothingness | (Sung landscape) |

| All | the natural world | objective existence | (Ming landscape) |

In addition to these (simplified) philosophical categories, derived from a summary (which itself simplifies Nishida's dynamic fusion of western and eastern philosophy, a paradoxically Idealist/Zen philosophy of “basho”) are the Indic and Greek mythic archetypes, plus the scientific (i.e. geological) elements in the sequence.

| Her | Shakti/Saraswati | Hera/Athena | Angkor Wat/OKC |

| Exists | Shiva | Hades | the geology of Oklahoma |

| Regarding | Vishnu | Poseidon | the geology of New Mexico |

| All | Brahma | Zeus | the geology of Arizona |

Why it is that I have piled various levels (scientific, philosophical, aesthetic and mythic) atop one another I am not quite sure. Nishida refers to his own synthesis as “the universal of self-consciousness.” For years I had considered HERA as “objective,” but from the neo-Idealist perspective everything appears to be “subjective.”

It does makes sense that religion, Chinese landscape painting and Idealism should be subjective, for even science, logic and mathematics are, after all, but products of the human mind. Nishida’s multi-layered terms, which are also interconnected vertically, have caused me to reconsider the relationships among all four books.

Hera and her three brothers (like Shakti and the Trimurthi) form a “family”; as do the three landscape types; Oklahoma, New Mexico and Arizona comprise three adjacent sub-regions (i.e., states) in the American Southwest, whose geologies accordingly will doubtless turn out to be a “family” of geological types as well.

(“Family” here reflects Hera’s function as goddess of marriage and, along with Hestia, the goddess of family. Zeus’ wife is also his sister (in All Zeus is joined to Aphrodite, another early goddess of the hearth). Likewise may Nishida Kitaro’s interrelated levels of the basho be regarded as a sort of “family” of concepts.)

*In clarifying Ch’eng I's theory of Li, i. e., Principles or Laws, Chu His says: “What are hsing shang, or above shapes, so that they lack shapes and even shadows, but Li? What are hsing hsia, or within shapes, so that they have shapes, but Li? A thing is a concrete instance of its Li. Unless there be such-and-such a Li, there cannot be such-and-such a thing.” He goes on to say: ‘When a certain affair is done, that shows there is a certain Li.”

Elsewhere: “For this reason, there are the Li for things already before the concrete things themselves exist.” In a letter answering Liu Shu-wen, Chu writes: “There are Li even if there are no things. In that case there are only such-and-such Li, but not such-and-such things.” For instance, says Fung, “even prior to the human invention of ships and carts, the Li of ships and carts were already present. All Li were present before the physical universe.”

See also Fung on Chu Hsi (and by implication Plato): “There is first the Li of consciousness; but by itself it cannot exercise consciousness. There can be consciousness only when Ch’i has agglomerated to form physical shapes, and Li has united with Ch’i. Thus the mind is an embodiment of Li by way of Ch’i. The distinction between mind and nature is that mind is concrete and nature abstract. The Mind can have feeling but nature cannot.”

F.

I imagine that you all have had enough of Chu Hsi for the time being, but I thought that some might be interested to know how the question of Subject and Object plays out in the subsequent development of Neo-Confucian philosophy. Fung Yu-lan, who studied with John Dewey at Columbia University and subsequently taught at both Qinghua and Peking Universities, should prove a fairly reliable guide.

According to Fung the philosophy of Chu Hsi in the Sung evolves very nearly into its opposite, first in the work of Lu Chiu-yuan. “For the former,” he says, “reality consists of two worlds, the one abstract, the other concrete. For the latter (Lu) it consists, however, of only one world, which is called the mind or Mind.” Thus what Fung calls the School of Universal Ideas leads to the School of Universal Mind.

In the Ming dynasty it develops into the thought of Wang Shou-jen, dit Wang Yang-ming (1472-1528), “in whose conception,” according to Fung, “the universe is a spiritual whole, in which there is only one world, the concrete actual world that we ourselves experience. Thus there is no place for that other world of abstract Li, which Chu had emphasized.” Here I condense a passage that Fung quotes from Wang:

The Master asked: “What is the mind of Heaven and Earth?” The disciple: “I have often heard that man is the mind of Heaven and Earth.” “And what is it in man that is called his mind?” “Simply consciousness.” “From this we know that in Heaven and Earth there is one consciousness. But because of his bodily form, man has separated himself from the whole.” Wang Yang-ming continues:

“My spirituality or consciousness is the ruler of Heaven and Earth, spirit and things. . . . If they are separated from my consciousness, they cease to be. And if my consciousness is separated from them, it also ceases to be. But they are all one body, so how can they be separated?” “From this,” says Fung Yu-lan, “we gain an idea of Wang’s conception of the universe, simply put: “Mind is Li.”

As in western philosophy, we have moved from a dualism to a monism. Wang again: “The mind of man is Heaven. There is nothing not included in it. We all are this single Heaven, but because of the obscurity caused by selfishness, the original state of Heaven is not manifest. When we extend our intuitive knowledge, we reduce the obscurity; when it is cleared away, our original nature is restored.”

G.

In Yung Sik Kim’s chapter on “Ch’i” (vital substance), in “Basic Concepts of Chu Hsi’s Natural Philosophy,” he cites Chu’s distinction between ch’i that has form and formless ch’i. “Air, for example, for Chu Hsi, represents formless ch’i,” says Yung:

Obviously air, which makes wind and constitutes a part of heaven, appeared to him to be invisible and intangible and thus lacking in physical form. Sometimes he even denied that bright objects like stars and candle lights had physical form or tangible qualities: they were “merely ‘congelations’ (ning-chu che) of ‘the exquisite’ (ching-ying) [portions of formless] ch’i.”

Professor Kim continues:

To Chu Hsi these bright things were not solid objects made of aggregated ch’i but mere gaseous existence made of formless ch’i and endowed with brightness. Thus, “the clear portion of ch’i becomes heaven, the sun, the moon and the stars” and “the extremely clear portion of the Fire [ch’i] produces things like the wind, lightning, the sun and the stars.”

However delightful these passages may be, they warn us that in Chu Hsi we are not dealing with a modern scientist (though his thought was undoubtedly progressive for the Chinese Middle Ages). As the professor points out, Chu Hsi’s curiosity had its limits. He “was not interested,” Yung Sik Kim remarks,

in the details of the process of aggregation, which accords physical form and tangible quality to formless ch’i and by which men and things come into being. Of course his remarks about the formation of the earth and the emergence of life hint that these processes may represent modes of such aggregation, or what he called “the spontaneous congelation of the yin and yang ch’i.”

H.

I had presented (to the best of my limited ability) the thought of Chu Hsi that resembles in its abstract, philosophical principles the “realism” of Plato and the “idealism” of Kant (and other modern westerners). I relied for this upon Wing-tsit Chan’s selections, Fung Yu-lan’s summaries and the early chapters of Yung Sik Kim’s study, The Natural Philosophy of Chu Hsi. The great bulk of his exhaustive book, however, concerns not only Chu’s relation to the early modes of Chinese thought mentioned above but also Chu’s use of, and relation to, the following traditional Chinese concepts (I am listing his chapter’s titles and some of their sub-headings):

Heaven (T’ien) and the Sages (Sheng-jen)

Stimulus-Response (Kan-ying and Pien-hua)

The pre-scientific theories of Heaven and Earth, including

Their origins, Their structure, The luminaries, The surface

of the Earth, The motions of the Heavens and the Earth,

The Moon’s Phases and Eclipses of Sun and Moon,

The Seasons and the Tides, “Meteorological” phenomena,

The Myriad Things (Wan-wu), and Man

In his final section, Professor Kim returns us to the question of “Chu Hsi and the ‘Scientific’ Traditions,” where he undertakes a comparison of medieval Chinese with western scientific theory and practice. Would it be of interest to have further reports on these matters, or is your inbox already too full of MM emails?

I.

Perhaps we might return for a moment to the The Complete Works of Chu Hsi. I had been quoting among others a passage that included, in translation, the word “experience,’ from a section titled “The Nature of Man and Things.” In the section that follows, “The Nature of Man and the Nature of Things Compared,” Chu Hsi says, famously:

Man and things are all endowed with the principle of the universe as their nature and receive the material force of the universe as their physical form. [“The principle of the universe” translates li and “the material force of the universe” translates ch'i.]

He quotes Lu Ta-lin (1044-1090) as having said that “in certain cases”

the nature of things approximates to the nature of man and in some cases the nature of man approximates that of things.

[As in Chinese literati landscape painting, I might add, where Man is represented in terms of Nature and Nature in terms of Man.]

I now revert to Yung Sik Kim, who in his chapter, “Heaven and the Sages” has a section titled “Man and Heaven.” (All subsequent citations here will be from this chapter by Professor Kim, except where Chu Hsi is himself quoting earlier authority.)

I begin by noting an important concept. The words for Heaven (t’ien) and Earth (di) are combined in a well-known phrase, t’ien-di, meaning the whole natural world. Kim says that “t’ien-di is contrasted with the human world.” To quote Professor Kim at length:

The relation between man and the natural world, “heaven” or “heaven and earth” — had many sides. For one, there was the idea of the parallelism of macrocosm-microcosm, the notion that man as the small universe is the epitome of the great universe, heaven and earth. Chu Hsi frequently made assertions that contain this idea. He said, for example, that “heaven simply is a great man, and man simply is a small heaven” and went on to compare the four human virtues with the four cosmic qualities. He said: “Man simply is a small child, and ‘heaven and earth’ is a large child”; “‘Heaven and earth’ is a great ‘myriad thing,’ and a ‘myriad thing’ is a small ‘heaven and earth.’” This idea was also expressed using ch'ien and k'un [the first two trigrams of the I Ching]: “Ch'ien and k'un are the parents of the world, and [one's own parents are] the parents of oneself.”

I pick up again with more commentary by Kim:

. . . the parallelism between man and heaven and earth even turned into an identity and into a mystical notion that man is one with the whole universe, and everything in the universe is within himself. Chu Hsi said that they [i.e. man and heaven and earth] are “one body from the beginning until now.” The same idea can be found in his following remark: “Heaven is simply man; man is simply heaven. In the beginning of man, he comes into heaven thanks to heaven. Once [heaven] has produced this man, then heaven is also in man. In general, speech, action, seeing and hearing are all heaven. As I speak, heaven is here.” This notion is also in line with his ideas about “the ch’i of heaven and earth” and “the mind of heaven and earth,” which man receives and makes his own ch’i and mind. At times the identity was not limited to man but was extended to all the myriad things. . . .

If I may bother you with one more extended quotation:

The most pronounced aspect of the relationship between man and heaven and earth, however, was the idea of the triad of “heaven-earth-man,” that is, the notion of the world in which man lives harmoniously between heaven and earth. A source of this view is the passage from the Doctrine of the Mean (the Chung Yung): “If [a man] can assist the transforming and nourishing of heaven and earth, he can form a triad with heaven and earth.” Commenting on this passage [Chu Hsi] wrote, elsewhere: “Man came into being between them [i. e., heaven and earth], where [things] are mixed and indistinguishable.” The relationship [says Kim] displayed by the idea of the triad is basically that man and heaven and earth complement each other. To be sure, heaven, or heaven and earth . . . do not do everything alone; there are some things that heaven cannot do, which man does for heaven.

Chu concludes by quoting from the Confucian Doctrine of the Mean:

Man is in the middle of heaven and earth. Although [they] are just one li, heaven and man each has its own role. There are some things that man can do but heaven cannot do. For example, heaven can produce things but must use man for sowing seeds. Water can moisten things, but [heaven] must use man for irrigation. Fire can burn things, but [heaven] must use man for gathering firewood and for cooking.

I offer this material by way of bringing Neo-Confucianism in relation to Confucius but also to the Confucian Aftermath. Do we not have here something like the contemporary scientific view of man’s relation to the universe? In a 1998 article a western physicist has discovered a correspondence between Superstring (or M) Theory and the mathematics of DNA. Such an astounding relationship suggests that life is implicit in the universe at large and thus that man is inherently (and explicitly) related to “heaven” and “earth.”

J.

Should you by any chance be wondering how Chu Hsi lines up with Plato and Aristotle (in his comprehensive system of knowledge he more closely resembles the latter), Wing-tsit Chan, who has devoted considerable time to the question, has this to say about their highest principles (which, in Chu Hsi of course means the Great Ultimate, tai-ji, expressed in circular form as the conjunction or alternation of the principles of Yin and Yang). Chu calls it “the highest good,” adding, “Each and every person has in him the Great Ultimate, and each and every thing has in it the Great Ultimate.” Now for Chan's comment:

Fung Yu-lan said, “The Supreme Ultimate is very much like what Plato called the Idea of the Good, or what Aristotle called God.” Recently Chang has compared Chu Hsi and Aristotle in the greatest detail so far. He points out that Chu Hsi agrees with Aristotle: that Ideas do not exist for themselves, that the Idea as the One does not exist apart from the Many, that matter exists in the sense of possibility or capacity, that matter and form exist together, that there is an eternal principle, which is at once regarded as form and moving cause, that matter is the ultimate source of the imperfection in things and that it is the principle of individuation and plurality, that an entity (God in Aristotle, Heaven in Chu) exists that imparts motion but is itself unmoved, and that it is pure energy, eternal, and good per se. However, although Chu Hsi is an Aristotelian in the field of nature, he is a Platonist in the field of moral values, recognizing that there exists an eternal, unchanging truth.

So much for the similarities. Chan now turns to the differences:

Needham rejects any comparison with Aristotle. He says, “It is true that form was the factor of individuation, that which gave rise to the unity of any organism and its purposes; so was li. But here the resemblance ceases. The form of the body was the soul; but the great tradition of Chinese philosophy has no place for souls. Again, Aristotelian form actually conferred substantiality on things, but . . . the ch’i is not brought into being by li, and li has only a logical priority. Ch’i does not depend upon li in any way. Form was the ‘essence’ and ‘primary substance’ of things, but li is not itself substantial or any form of ch’i . . . I believe that li is not in any strict sense metaphysical, as were Platonic ideas and Aristotelian forms, but rather the invisible organizing fields or forces existing at all levels within the natural world. Pure form, for Aristotle, pure actuality was God, but in the world of li and ch’i there is no Chu-tsai [Director] whatsoever.

Here a comment by Randall Collins (The Sociology of Philosophies (Cambridge, MA: Harvard U.P., 1998) might be useful in clarifying the comparison of Greek with Chinese philosophy:

It is the Chinese language, with its dearth of explicit syntax, that had prevented Chinese philosophers from developing syllogistic logic and pursuing such a route to epistemology. Time is elided, because verbs lack tense. Nouns do not distinguish singular and plural, abstract or concrete. Without the definite article most things appear as mass nouns, with no distinct emphasis given to the particular. Realms of philo- sophical consideration are cut off. What is constructed in the characteristic Chinese world view is language-embedded. The same word can often be used as noun, adjective or verb, giving the haunting multiple meanings of Chinese poetry, while avoiding the Greco-European style of philosophizing by piecing apart abstract distinctions. To this quality of language is due the centrality of concepts such as Tao, a Chinese blending of process and substance. No abstract metaphysics is possible.

Whereas Neo-Confucianism was essential, historically, to the process of formulating a common view of Confucius (it was Chu Hsi himself who compiled and edited the canonical “Four Books”), only with the introduction of western philosophical abstraction, we might say, could cultures as different as the Japanese, the Korean, the Chinese and the Vietnamese begin to formulate a common view of themselves based upon generalizations in turn dependent upon abstract metaphysics. Thus my current project. Are we making any progress?

Whatever the case, let us now turn to a “Post-Confucian” aspect of China.

MM as Confucian, Neo-Confucian and Post-Confucian