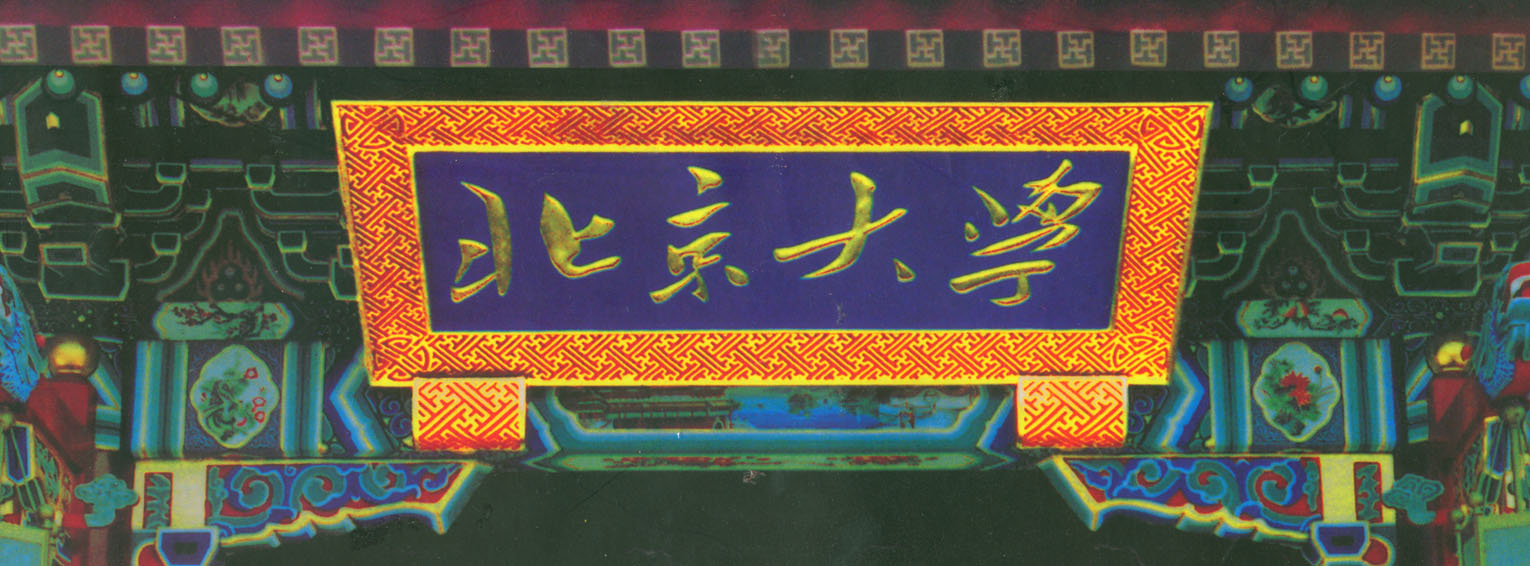

The following text was commissioned by the Thai Graduate Institute of Peking University and delivered as a lecture at The School of Foreign Languages during a five-day visit to Beijing, November 20-24, 2006 to an audience of faculty and students from the Southeast Asian Graduate Institute.

北京大学外语学院东方语言文化系 Madison Morrison讲座:《东南亚与欧洲的类比》 2006-11-24 教育部非通用语种本科人才培养基地 东南亚研究所所长张玉安教授向Madison Morrison博士赠送纪念品 东南亚研究所邀请Madison Morrison博士给研究所成员和研究生进行了一次学术讲座, 讲座的标题是《东南亚与欧洲的类比》。Madison Morrison博士多次到东南亚考察研究, 积累了大量东南亚感性知识和理性思考。 Madison Morrison博士的演讲以东南亚国家与欧洲国家在地理上的对比开始, 着重讨论了东南亚国家在宗教、政治和历史发展方面的特点。演讲结束之后, 东南亚方向的研究生就研究方法、研究对象的比较等方面的问题与Madison Morrison博士进行了讨论。

Analogies between Southeast Asia and Western Europe

For the past half dozen years I have been traveling quite extensively throughout Southeast Asia: to Thailand and Cambodia, Malaysia and Myanmar, Vietnam and the Philippines, always returning to a seventh location, Taiwan, which itself is part of the same geographical theater. Within my purview have been not only these half dozen Southeast Asian countries, all which I have written about elsewhere, but two more countries that I have not yet visited, Laos and Indonesia, along with Singapore, which I have visited twice but never written about. Just as the world in general tends to grasp the Middle East through the medium of English (and to a lesser degree, French), so it forms its view of Southeast Asia. A recent book by a dozen Japanese scholars is a case in point.

Written in English, these essays attempt to re-conceptualize the region not through individual country studies by Southeast Asian language specialists but rather through the work of a dozen Northeast Asian scholars writing about the whole region in our now universal language. English, I notice, is also the medium for a second new collection of essays, postcolonial studies that take up in turn each of the nine countries. Its authors include a mix of Europeans and Americans, South and Northeast Asians, plus natives from the countries examined. I am not sufficiently informed to address the question of Southeast Asian expertise in China, India, Russia or elsewhere, but I would not be surprised to find examples of this research available in English too.

So there is something appropriate about my linguistic incompetence. Though I find that I can speak to 30 per cent of the residents of Phnom Penh in Mandarin (and make myself understood to speakers of chaozhou hua in Bangkok), though I have bought French books in Cambodia and Vietnam, along with Spanish books in the Philippines, I neither speak nor read Burmese, Thai or Lao, Cambodian, Vietnamese or Malay, Pilipino, Indonesian or any of the region’s other languages, such as Tamil. To compensate for my linguistic deficiencies in these individual cultures, I have enlarged my topic to address the more general culture of Southeast Asia, here construing the word “culture” anthropologically to include history, geo-politics and religion as well as the arts.

Moreover, as you may see from my title, I have broadened my topic even further by proposing a series of analogies between Southeast Asia and Western Europe, including their historical and cultural development and implying their comparative situations in the present-day global context. After a few more introductory remarks, I will proceed under five headings, as follows:

Similarities in the geography, demographics and history of the two regions

Buddhism and Christianity, respectively, as their principal religions

The political structure of the two regions, with reference to I and II

The development of Buddhist kingship in Thailand

Further observations about the import of Buddhism and Christianity

Three earlier general books about Southeast Asia represent a persistent way of grasping it: (1) An American high school text of 1960 titled Southeast Asia, (2) Milton Osborne’s Southeast Asia: An Introductory History, first published in 1979; and (3) an American travel guide of 1989, also titled Southeast Asia. The first, pedagogical book breaks up the geographical area into discrete geopolitical units, viewing each country under a naive rubric: Communist vs. Capitalist. The second study, a work of much greater sophistication, nonetheless retains this country-by-country framework. The third treats in detail only five countries (The Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia) but includes an Introduction to the whole region.

Copies of (1) and (3) I have donated to the Thai Graduate Institute of Beijing University (along with the re-conceptualizing and postcolonial studies); (2) is readily available in paperback reprints. As for (3), let us take a closer look at this travel guide for its more recent, but not quite contemporary, view of its subject. Its authors begin with a geological history, an enumeration of flora and fauna and geographical observations, followed by a discussion of the following topics I-V and their subtopics:

A Cultural Crossroads

Mingling of ethnic groups

A legacy of ancient empires

The colonialists arrive

Influences from outsiders

Indian culture

China’s contribution

European influences

Divergent Life Styles

Rural living

City life

The Area’s Religions

Hinduism

Buddhism

Others

Festivals

Buddhist festivals

Muslim festivals

Something for everyone

Architectural treasures

A breath of fresh air

The entertainment scene

Culinary pleasures

Under “Flora and fauna” it is noted that rice is the basic crop of Southeast Asia, a somewhat pedestrian observation but one that on reflection, and by extension, proves a key to much that we can to say about the unity of Southeast Asian cultures. For if we take “culture” to mean “cultivation” (in this case, “agriculture”), a unifying element has been identified, one also relevant to high culture. Southeast Asia is predominately rural (see “A breath of fresh air”), not urban. Dependent upon the weather, its people share the fatalism characteristic of cultures tied to the land, to the seasons’ vagaries, to the forms of social organization associated with such an ineluctable agrarianism. Much of the region is riparial or riverine, even in largely landlocked Cambodia and Laos.

Due to its location, Southeast Asia has defined itself historically as a crossroads of trade (from Japan to India to the Middle East, and back). Under “a legacy of ancient empires,” notes the Introduction to our travel guide, “the eighth century A.D. saw the rise of the Sri Vijaya empire in Sumatra, whose authority swept across the islands of Indonesia and the Malay peninsula”; in Cambodia “the Khmer reign, which controlled much of the Southeast Asian peninsula between China and the Gulf of Thailand, lasted from the ninth through the fifteenth centuries”; “in 1236 the Thais, emigrants from China, founded the Sukhothai kingdom on the peninsula, followed by the kingdom of Ayuttaya in 1350.” Thus is early agrarian history redefined in dynastic terms. “Entertainment” and “culinary pleasures” were ubiquitous then as now.

These great civilizations, Vijaya, Angkor and Sukhothai, we know principally from their architectural remains, for in such tropical climates all other written inscriptions, principally on palm leaves, had a life span of no more than half a century. By “architectural remains” we mean religious monuments, which, though they record the effects of trade, feature military exploits, epic adventures and representations of divinity. Because other remnants are so sparse, we tend, therefore, to think of the region’s early “culture” in terms of the Angkorean temples at Siem Reap, the Siamese pagodas at Ayuttaya and Phimai, the Hindu and Buddhist edifices of central Java, and the thousand Buddhist temples spread out before Bagan in modern Myanmar.

Under “The colonialists arrive” the travel guide enumerates “the Portuguese, Spanish, British, Dutch and French,” to which list might be added the Americans. Under “Influences from outsiders” it notes that “The region’s most important influence came from India,” that China’s influence “was slight by comparison” and that China’s “most important contribution was its people.” Another valuable point: “It is in the region’s cities that the European influence is most prevalent.” This leads to several other observations: (1) “The ancient empires of Southeast Asia considered cities to be merely ceremonial or symbolic centers.” (2) “The strength of the empire remained in the countryside with the scattered villages of farmers, who fed the slaves and soldiers of the king.”

Two comparative points follow: (3) “In Europe, however, it was cities that provided the focal point for survival and the development of culture.” (4) “Consequently, when the colonial powers constructed cities in Southeast Asia, they built them to endure as power centers, as harbor-hugging towns along major shipping routes.” It is these shipping routes that conveyed to the nascent individual cultures of Southeast Asia those exotic elements that would eventually be assimilated into, or come to dominate them, producing the amalgamations so characteristic of the region: an Islamicized Malaysia, a Hinduized Indonesia, a Sinicized Vietnam, to name three examples. This story parallels in many ways the development of modern European cultures.

Let us, then, for a moment take a further step back from the two regions, Western Europe and Southeast Asia, to compare their modern geopolitical components. The principal political entities of these two very different geographical areas are remarkably similar in many respects, to wit:

Thailand and France, central to their respective regions, both have populations of roughly 60,000,000, and are comparable in geographical extent as well as in the antiquity and development of their distinguished cultures

-

Vietnam and Germany, more volatile, each the product of repeated struggles toward unification, both have populations of 85,000,000. The two are also comparable with one another in physical size and in their hybridized cultures

-

Spain and Myanmar, more marginal, both have populations of 45,000,000, are similar in physical location and size, and also stand slightly apart, culturally as well as geographically, from their neighbors

Moreover, in our analogy, the minor countries of Southeast Asia (such as Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia and Singapore) may be compared with various minor countries of Western Europe (such as Holland, Belgium, Portugal and Switzerland). Southeast Asia has no equivalent of the Scandinavian countries, with their independent cultures, but again along the southern tier of both regions we find striking analogies:

-

Indonesia and Greece, both archipelago nations, served as the sites of many civilizations, the Ho-ling, Mataram, Sri Vijaya and Mahapajit (in Indonesia); the Minoan, Mycenaean, Athenian and Hellenistic (in Greece)

From one point of view the vast geographical array of Indonesia, with its more than 13,000 islands, might provide a collective analogy for all the European, historically Europeanized, or westward-leaning countries of the Mediterranean: Italy, Turkey and Egypt, as well as Greece. As a recent book about Indonesia summarizes the matter,

The South China and Java Seas, bounded by the islands of Kalimantan, Sumatra and Java, and by the Malay Peninsula, have been compared by some historians to the Mediterranean Sea in terms of the role they have played in the region’s history. The peoples living on the littoral of these Indonesian seas did not form a single community any more than did their counterparts in the Mediterranean region. But they have long been linked by ties of trade, religion and language, which helped to create a network of cultures that are all related.

If we take a less grandiose view of Indonesia, however, we might identify yet other analogous pairings in the Southeast Asian seas and the Mediterranean:

-

Malaysia and Italy, for example, are both peninsulas, Malaysia holding as secondary possessions, Sabah, Sarawak and historical Singapore, Italy, Sardinia, Sicily and the historical territory now occupied by the Papal State

Moreover, these southern appendages, Italy and Malaysia, bear a similar relationship to their respective continents. Both have also been great maritime centers (compare the ports of Genoa and Venice with those of Penang and Singapore).

-

We might even draw an analogy between marginal Brunei and such marginal “European” entities as Alexandria or Ephesus. Whereas Southeast Asia has nine countries, Western and Mediterranean Europe have about twice as many

Let us briefly extend (4) and (5), those analogies between Indonesia and Greece, Malaysia and Italy. The two archipelago nations historically had centers of power that progressively eclipsed earlier centers, not only among their own loosely federated states but also within their regions. Among the other islands of the archipelagos, however, there periodically arose independent states. In addition to Crete and Athens, Greece has had civilizations that flourished on Rhodes, Chios and Delos, among other islands; likewise Indonesia has had far-flung enclaves (Bali and East Timor are modern examples).

Throughout the ages trade has been important to both civilizations and with it their ship-building industries. Likewise parallel is the development of nationalism in Greece and in Indonesia, the first occurring in the 19th, the second, in the 20th century. Greece has been subject to repeated invasions (the Doric, Turkish and German, to cite only three); similarly Indonesia has been subject to invasions (the Indian, Chinese and Japanese). Out of Asia Minor came the great epics of Homer in their Hellenized form. Out of an Indic lineage came the great epic of Indonesia, the Negarakrtagama.

Modern Indonesia and Malaysia are the great exceptions to the general Buddhist culture of the region. Before we return to continental Southeast Asia, let us consider these two Islamic realms a little further. Indonesia, the more cosmopolitan of the two, through its trading contacts witnessed the importation of three of the world’s great religions, Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam, “with all their associated linguistic, scientific, legal and administrative achievements and values,” adds a contemporary historian. However, since these importations “were not spread evenly across the archipelago,” “even where they were influential,” they were never adopted in their entirety. So for several reasons, not least of all its vast reach, the Indonesian has proved a mixed culture.

Malaysia’s mixture of cultures has even more to do with its progressive waves of immigration: from Dravidian South India, from the Southern provinces of China, from the Middle East. “Great streams of history, and of peoples, for centuries met at that spit of land at Asia’s south-eastern extremity,” says Virginia Matheson Hooker, who elaborates upon the nation’s yet earlier accession of diversity as follows:

1. From the earliest times of human habitation the inhabitants of the northern areas of the Peninsula had contact with the peoples of what are now Burma and Thailand.

2. Those living in the southern parts of the Peninsula had contact with peoples on the nearby coasts of eastern Sumatra and probably western Java and western Borneo.

3. Dwellers in the coastal areas of Sabah and Sarawak were in contact with peoples in the nearby islands of what are now the southern Philippines and Sulawesi as well as with those across the South China Sea in southern Vietnam and Cambodia.

Malaysia, in short, has always been multi-ethnic and culturally pluralistic, though Islam came, and came to stay, of late determining the country’s very identity, strengthening the body politic by displacing colonial powers and providing the education, through new-style Anglo-Islamic schools ( madrasah), capable of enforcing its doctrines.

In an almost contradictory way, however, Malaysia’s history has also been determined, economically and politically, by its position as an entrepôt. For centuries its centers of trade and power have been subject to sudden removal, almost from each dynasty to the next. I will not bother to enumerate the names of all the Malaysian cities that have served the dual function of entrepôt and political capital. Suffice it to say that they are comparable in their variety and far-flung geography to such Mediterranean centers of maritime commerce as Jaffa, Ephesus and Istanbul; Alexandropoulos, Salonika, Piraeus and Amnisos; Venice, Naples and Genoa; Marseilles, Barcelona and the various ports along the North African coast from Gibraltar to Carthage.

Thus Malaysia no less than Indonesia (both countries are historical models of the multi-cultural) has latterly come to be dominated by a single religious doctrine, more liberal than that of its Arabic counterparts, but nonetheless increasingly exclusive. What distinguishes Malaysia and Indonesia, then, from mainland Southeast Asia, is their faith in the teachings of Islam, which in both cases have become an integral part of their national identity. The European analogy would be Turkey, another tolerant Islamic state, like Malaysia aspiring to modernity (Turkey, to European status) but constrained by its conservative culture and religious mores. Unlike Turkey, Malaysia and Indonesia are geographically diverse, their civilizations dispersed among many centers.

Incidentally, the official language of Malaysia, like that of Indonesia (and of the Taiwanese aborigines), is Austronesian, a linguistic substructure that in the early history of the region served as its lingua franca (much as did the Hittite of very early Europe, the koine dialektos of the late classical Mediterranean or the Latin of later European history). Thus these important southern nations are set off from their counterparts on the mainland, where a Mon Ur-language, Australasian, lies beneath the present-day languages of Vietnam, Thailand, Cambodia and Myanmar. Only Lao, a dialect of Thai, is of clear derivation. Sanskrit, though it has played a role in the development of their written forms, is not linguistically fundamental to any of these languages.

As in Indonesia, so in Malaysia Buddhism arrived along trade routes. After Islam had spread throughout the Middle East and on to India, the Abbasid culture of kingship eventually reached the archipelago empires. In Malaysia, the penchant for authoritarian government, observable during, but also since, its colonial phase, may be understood in terms of the assimilation of such an element from the Muslim world. In this regard we might again compare Malaysia with Italy, whose political tendency from the Roman principate to the fascist Mussolini, reflects an inherent authoritarianism. In this interval both countries have witnessed a continuous contest between religious and civil authority, Islamic imams and Catholic popes competing with secular powers.

In the modern period both countries have also experienced hostility from and toward their neighbors: Malaysia in its dealings with Indonesia, Italy in its dealings with Greece (the roots of the latter hostility discernible in their antique relations). On the political front, historical Italy, in Sardinia, Sicily and its southern provinces, like Malaysia more universally, has been subject to colonization, the Italians at the hands of the Greeks, the Malays at the hands of the British and the Japanese. Both cultures are the products of indigenous elements (see Italy’s Etruscans and Malaysia’s Malays) but both have taken shape under more important, exotic influences. (Present-day Singapore and Cyprus illustrate admixtures of various cultures gradually compounding.)

Such cultural mongrelism in the case of Malaysia represents an amalgam of the Indian (Hindu and Buddhist) with the Chinese; in the case of Italy, of the classical (Greek and Roman) with the Roman Catholic. The analogy between Malaysia and Italy, however, breaks down when it comes to their modern artistic cultures, which are not comparable. For Italy is one of the world’s leaders in music, art, architecture and literature, whereas Malaysia is still struggling to transcend folk customs and emerge on the stage of world culture. Italy, on the other hand, does not approximate Malaysia’s multi-ethnicity: as late as 1921 the ethnic Chinese and Indians in Malaysia outnumbered the Malays. The greater ethnic homogeneity of Italians may explain their greater cultural unity.

I have spoken at some length about the major Islamic countries of Southeast Asia. Other countries, such as Myanmar, Thailand and Cambodia, have Islamic minorities, and Singapore strives to keep the Islamic, Hindu and Christian elements in balance with its dominant, modernized Chinese culture. Christian minorities in Asia are on the rise, most notably in Northeast Asia (Korea has 10,000,000 Protestants), but also in Southeast Asia (the Philippines has a new sect). Catholicism was originally associated with the colonial presence of Portugal and Spain, Protestantism, with the colonial rule of the Dutch. In recent times both Christian sects have been spread by more neutral missionaries, whose humanitarian goals have been more comfortably received.

Having noted the region’s minor religions it is time to address the question of its major religion, which is to say Buddhism, in its two principal forms: Mahayana doctrine, practiced principally in Vietnam, and Theravada doctrine, practiced throughout the other non-Muslim countries. My aims will be to consider Southeast Asian Buddhism in relation to Western European Christianity, to assess the two cults’ relationships with regional politics, and to reach some conclusions as to which role each has played in the success or failure of its region, in its economic prosperity, in war and peace, in the health of the body politic, and finally in the institutions of kingship and modern democracy. Much that I have to say here may be regarded as controversial.

First a few generalizations about the two religions. (Incidentally, in what follows I speak neither as a Christian nor as a Buddhist.)

-

The two religions are propelled by teaching (in their lifetimes both Buddha, with his five disciples, and Christ, with his twelve, set the pattern for proselytism)

-

Both Buddhism and Christianity have been widely assimilated by a variety of cultures hitherto not sympathetic to such exotic teachings

-

Unlike Islam, Hinduism or the teachings of Confucius, Buddhism over the past two centuries has also spread to devotees in the West

-

Similarly, and in this unlike Judaism or ancient Egyptian doctrine, Christianity has also spread throughout the East, indeed throughout the world

Both Buddha and Christ preach renunciation and non-violence. Among the cultures that practice their doctrines it is not quite clear, despite the protestations of their followers, whether the culture in question is more bellicose or more pacific as a result of Buddhism or Christianity. One notes, for example, that since the time of Rome, most western empires have been Christian. In Southeast Asia, the Khmers, the Thais and the Burmese have been notably destructive, despite their nominally pacific faith.

Strictly speaking, no text written by either Buddha or Christ survives, though the Sutras purport to represent the words of Buddha, and the New Testament gospels freely quote Christ’s words from memory. Perhaps this lack of direct authority has encouraged the development of the sangha (the Buddhist monkshood) and the Christian brotherhoods (of monks, priests and preachers). Effectively, however, both religions are notably personal. This may be due in part to both religions centering upon an individual. Though Buddha and Christ are traditionally represented as men, both were conceived under unnatural circumstances. At the Buddha’s birth a white elephant appeared with a lotus atop his head; at the birth of Christ angels appeared and shortly thereafter the three Magi. According to these mythologies, Buddha was born from his mother Maya’s side, Christ from his mother Mary’s immaculate conception. Thus are the personal and human foundations of both religions qualified by contradictory divine myths.

Typologically Buddhism arises out of polytheistic Hinduism, whereas Christianity arises out of monotheistic Judaism. This may explain a good deal about the differences and similarities between Southeast Asian and Christian cultures. For though the principle of death and rebirth is common to both Buddhist and Christian lore; though they both include a Heaven and a Hell; though their cosmologies are also populated with spirits or angels; though Buddhists and Christians alike hold deliberative Councils, elaborate their doctrines into complex theology, philosophy and even logic; nonetheless there are differences between these faiths that return us to their respective polytheistic and monotheistic origins. Such differences we will take up again, after we have considered the Buddhist and Christian concepts of nationhood. Before we do so, however, it might be helpful to discriminate between Mahayana and Theravada doctrine; later we will also discriminate briefly between Catholic and Christian theology and practice.

There are three principal schools of Buddhist doctrine: Mahayana, Theravada and Vajrayana. The Mahayana migrates north from India into Tibet, thence to China, from which it later descends to Vietnam and other Southeast Asian locations. From China it is transmitted further east to Korea and Japan. Theravada devolves from India to Sri Lanka, where it takes root, is codified and thence disseminated to Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia and Laos, as well as to other Southeast Asian locations. Vajrayana is first known in Tibet, where it merges with the shamanistic Bon religion, then in Bhutan, Mongolia, Sikkim and Nepal, to which countries it is later transmitted. The northern Greater Vessel (Mahayana) represents a more severe discipline, as indicated today by the grey robe of the Chinese monk or the black robe of the Japanese; the southern Lesser Vessel (Hinayana, or Theravada) is more lively, as indicated by the orange robe of the Southeast Asian monk, sometimes varied to indicate hierarchy and sect by the red, maroon and brown robes that I have often observed in Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand and Myanmar. I quote now from authorities on the distinction between Theravada and Mahayana:

Jack Maguire: “The Theravada vehicle teaches a rational view of the universe, whereas the Mahayana vehicle presents a more metaphysical vision, including the notion of absolute qualities and bodhisattva powers [i.e., the powers of the not-yet-realized Buddha], which exist on a universal rather than human scale.”

Hans Wolfgang Schumann: “In relation to the world-as-is, Theravada maintains a psychological realism; Mahayana, an idealism. Consequently, Theravada regards suffering as real, Mahayana, as illusory.”

Jack Maguire (again): “Theravada is associated with a reverence for scholarship, wisdom and all-knowingness. Its practice, therefore, can include especially rigorous educational and intellectual training. Mahayana is commonly considered to place more emphasis on intuitive, experiential and imaginative understanding.”

Mahayana Buddhism suggests the severity of Calvinist or Jesuit theology, both intellectually severe, whereas Theravada doctrine, like Christian compassion, is directed toward assisting others through engagement in the world. The Mahayana student, who seeks to become a bodhisattva, postpones his own nirvana.

Of the two sects, Mahayana is the more textual. Its words of wisdom and commentaries may be grouped as follows:

The Sutras, e.g.,

Prajnaparamiti, or the Sutra of wisdom that reaches the other shore

The Heart Sutra

The Diamond Sutra

The Saddharmapundarika, or Lotus, Sutra (the Buddha’s essential teachings)

The Shastras (treatises), or points of doctrine

The Tantras (texts): esoteric teachings

Here the patristic texts of the Roman Catholic Church might be seen as analogous. As the Church Fathers wrote in classical western languages, so the founders of Mahayana doctrine wrote in Sanskrit. The canon of Theravada doctrine, originally recorded in classical Pali, was transmitted in this ancient language to Southeast Asia.

The principal Theravada texts may be grouped as follows:

The Vinaya-pitaka (“The Basket of Order”), which includes the Dhammapada

The Sutra-pitaka (“The Basket of Teachings”), which includes discourses of the Buddha and his disciples, plus over 500 Jataka tales

The Abhidharma (“The Basket of Special Learning”), advanced monastic teachings

These three categories are known as the Tripitaka (“The Three Baskets”). The southern transmission of Theravada doctrine began in 250 B.C. Ashoka, the Indian emperor, through his emissary, the monk Mahinda, converted the king of Sri Lanka; later the Pali texts were transcribed, in 43 B.C., under the threat of extinction by an invasion of non-Buddhists. Much later, from Sri Lanka (Ceylon) they were disseminated.

By the sixth century A.D. the Theravada doctrine appeared in Southeast Asia, principally in Bagan, under King Anawrahta, henceforth throughout Myanmar. But the larger indoctrination of the peoples of the region began in Thailand, where, in the 13th century Sri Lankan missionaries converted the Thai king; thereafter, in Cambodia, and finally in Laos, to which it spread in the 14th century.

In a nutshell, according to Theravada doctrine:

The student strives to become an Arhat, or spiritually enlightened person

He seeks self-perfection through moral conduct

Through this process he achieves nirvana

Here we are principally concerned, however, not with the individual soul as much as with the social and political implications of the doctrine. According to an historian of the sect, “Theravada has a long, solid tradition of creating strong, tightly knit, well-functioning monasteries. Throughout history these institutions have been skillful at allying themselves comfortably with the surrounding and political powers without overtly compromising their own integrity.” (We might here compare the political history of the Roman Catholic Church.) According to the same historian, “Mahayana has had a more volatile monastic history, befitting its relatively more complex involvement with the population at large and therefore its greater vulnerability to social and political crosscurrents.” (We might here compare the history of Protestantism.)

Like Christianity, Buddhism is a religion of social responsibility. In this it shares an ethos with Confucianism and diverges from its origins in Vedic Hinduism, which, like Daoism, is a less humanistic vehicle. Like Christianity, Buddhism reinforces Democracy, because both doctrines are personal. Yet in recent centuries its doctrines have been enlisted in support of Buddhist kings. Likewise have modern Christian kings, by promulgating the doctrine of their Divine Right, defined their monarchy. Rather than seeking doctrinal substantiation of Buddhism’s role in this regard, let us return to history and the chronicle of a central country, Thailand, where we find perhaps the most profound Buddhist influence on politics and statehood. We will also glance at Laos so as to fill out our Southeast Asia-Western Europe analogy.

Buddhist doctrine, as we have indicated, progresses slowly across continental Southeast Asia, from West to East (Burma to Thailand to Cambodia). So that we may study its influence upon the most practical human behavior, let us focus upon Thai politics, drawing upon the recent Cambridge History of Thailand (2005) by Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit, the first new comprehensive study of the subject in thirty years. We do not normally think of Buddhism as offering a political theory for governance, much less an actual polity, but in the history of three continental powers we can see Buddhism figuring not only in the development of nationhood (as in Burma), the expansion of empire (as at Angkor) or the resistance to revolutionary tyranny (as in modern Cambodia) but also in the theory of the modern state (as in Thailand).

In 1767 the Burmese conquered Ayuttaya and notoriously leveled the city. “From the 1760s to the 1860s,” Baker and Phongpaichit tell us, “several pretenders emerged to occupy the vacancy left by the obliteration of the city and the dynasty. Among these Pyaya Taksin rose to power, establishing a new capital, Thonburi, surrounded by a swamp that was good for defense, situated opposite an old Chinese trading settlement at Bangkok.” In terms of political theory “He brought back the traditions of the warrior-king and militarized society.” Taksin was a man of humble origins. Tongduang, one of his most successful generals, “was adopted as leader of the old nobles, who resented their own exclusion from office and . . . were disturbed by Taksin’s origins, supporters and ‘abnormal’ rule. . . . In April 1782 they mounted a coup, executed Taksin on the grounds that he had become mad, purged his relatives and followers and then placed Tongduang on the throne as King Rama I.”

“The new regime,” the authors continue, “portrayed itself as a restoration of Ayuttaya tradition in reaction against the abnormalities of Taksin’s interregnum. The capital was moved across the river to Bangkok and built on similar principles to Ayuttaya. . . . Gradually the kingdom expanded through military conquest. Bangkok had emboxed a new outer ring of tributary states in the south, north and east. The chronicler of Rama I boasted: ‘Its kingdom is far more extensive than that of the former Kings of Ayuttaya’ . . . The great households expanded by accumulating wives to produce enough talented sons to sustain the family’s standing in the senior official ranks and enough daughters to build marriage networks within the elite, in support of the king. The royal clan showed the way: Rama I had 42 children by 28 mothers; Rama II, 73 children by 40 mothers; Rama III, 51 children by 37 mothers; Rama 1V, 82 children by 35 mothers; and Rama V, 77 children by 36 mothers. . . .

“The pre-1767 trend towards Buddhist kingship was now realized. Brahmanism was not rejected; court ceremonies were retained; and the site of the new capital was dubbed Rattanakosin, Indra’s jewel, or Krungthep, city of angels. The monarchy was again hidden and mystified. But royal legitimacy did not appeal to any identity between king and god. Rather, the king claimed to be a bodhisattva, a spiritually superhuman being who had accumulated great merit over previous lives, been reincarnated to rule with righteousness and would become a Buddha in the future.” Thus during this period Buddhist kingship was idealized. The new Bangkok monarchy was celebrated as defenders of Buddhism against the destructive (albeit Buddhist) Burmese. “The conquests of Lao and Khmer territories were justified as saving these people from less perfectly Buddhist governance.” By force of example a Buddhist ideology of kingship had been established, one that persists to the present-day.

“Under this theory the main purpose of kingship was to help the people ascend the spiritual ladder towards the ultimate goal of nirvana, the release from worldly suffering.” It was the king’s duty “to prevent the decline and eventual eclipse of Buddhism foretold in the classic texts, especially by purifying the sangha and making corrected recensions of those texts. . . . Rama I passed laws to rectify the lapses in monastic discipline during Taksin’s reign. He assembled a council of senior monks to compile a recension of the Tripitaka . . . and commissioned two new versions of the [Buddhist] cosmology. So that people should not practice Buddhism ritualistically but [rather] ‘understand the Thai meaning of each precept,’ he founded a school to re-educate the monks and had several Pali texts translated into Thai. . . . The walls of the wat were painted with murals . . . based on the Jataka tales, which showed how the future Buddha was to achieve spiritual perfection [leading to] enlightenment. . . .

“The king even sponsored annual chanting of one of these tales to teach moral values and dramatize his own authority as a bodhisattva.”

Now we skip ahead to King Mongkut, the brother of Rama III, who in the mid- 19th century instituted progressive changes, many inspired by western developments. “The strategy of Mongkut’s group,” the Cambridge history continues, “was to split the material from the moral. . . . [Mongkut] explicitly rejected the traditional [Traiphun] cosmology and urged children to learn modern science so as to accept a scientific view of the world. [He] embraced the idea that people were not bound by fate but were [instead] capable of improving the world. Thus history was possible.”

King Mongkut himself “began to research and write Siam’s history, commis-sioning a member of his court, Thiphakorawang, to pen a new version of the royal chronicles, which described kings making history rather than reacting to omens and fate. . . . Thiphakorawong’s book for children advised readers to reject Christianity.” In it the courtier argued that “every religion, including Christianity and Buddhism, incorporate[d] miracles and magic from folk beliefs. But [that] once these were removed, Buddhism’s reasoned precepts were more in line with a rational, scientific mentality than the will of Christianity’s god (‘a foolish religion,’ he called it). . . . While in the monkshood between 1824 and 1851 Mongkut [had] formed the Thammayut sect, partly to cleanse Buddhism of the elements that attracted [foreign] criticism, partly as an extension of Rama I’s ambition to a more moral [Buddhist] authority to order society.” At mid-century, however, Thailand faced new pressure to westernize.

“In 1842 Britain humbled China in the Opium Wars, showing the consequences of defying British demands for ‘free trade.’ The impact of the war ruined the Siam-China junk trade and persuaded Siam to look to westerners for a substitute. The British victory also meant that both India and China, sources of much of Siam’s old culture, had fallen under western domination. Increasingly, the elite’s gaze swiveled westwards.” Unlike others in the region who succumbed to bad modern ideas and relinquished their earlier traditions, the Thai monarchy showed the way by an enlightened assimilation of new with old and by reviving those elements in the culture that would benefit the realm even in the face of a necessary modernity. To cite one example, Mongkut returned to ritual as a way of reinforcing the people’s allegiance to the institution of monarchy. Then, in 1868, the king’s son, Chulalongkorn succeeded his father and over his 42-year reign replaced the old political order with the present-day nation-state.

Chulalongkorn began by traveling abroad to study successful forms of govern-ment elsewhere. He witnessed “‘progress’ at first hand in the colonial territories of Singapore, Java, Malaya, Burma and India ‘to select what may be safe models for the future prosperity of this country.’ He sent twenty minor royalty for education in Singapore. He had several European constitutions translated into Thai and found himself most impressed by the French Code Napoleon. . . .” He abolished slavery, equipped his troops with western weapons and paid them a regular salary. He established a bureaucracy. “The resulting structure looked uncannily like the colonial government of a British Indian district.” Nonetheless he adopted this model and fashioned it into an instrument for successful governance. “The old semi-hereditary governing families of the provinces were superseded by central appointees. . . . New official enclaves were built in the old provincial centers. . . . Judicial reform followed.”

This overlapping of old and new systems was typically Thai. As a cultural property it might be regarded as the impulse that underlies the successful fusion today of kingship with constitutional government. Like the Thai conception of borders, which represent a no man’s land of overlapping interests rather than a western geographical precision, two overlapping systems are seen as superior to a single, more rigorous system. Compromise is built into the Thai gene pool, it would seem. But not all new ideas could be resisted or readily assimilated. The French, or those returning from education in France, for example, introduced to Thailand the western concept of historical claims to sovereignty. Though attractive to modernizing Thais, the French also caused difficulties by insisting upon their historical claims to Thai territory.

Chulalongkorn instituted a system whereby “all men were now the king’s men. Almost everyone stood in the same relationship to the state for tax and military service.” In a parallel development, all Thais were reinvented as members of the same race. When he went abroad “Mongkut had signed himself Krung Sayam; Chulalongkorn signed himself Sayamin (Siam + Indra). During his 1872 visit to India, Chulalongkorn described himself as ‘King of Siam and Sovereign of Laos and Malay.’” Thus Chulalongkorn blended Thailand, Malay, Laos and the Shan territories together: “‘The Thai, the Lao and the Shan,’ he said, ‘all consider themselves peoples of the same race. They all respect me as their supreme sovereign, the protector of their well being’. . .

“Under the Nationality Act of 1913 everyone born inside Thailand’s borders could claim Thai nationality.” This solution to the problem of ethnic diversity within a unified body politic proved highly influential upon the modern Malay redefinition of race, statehood and citizenship. “The Thai definition had laid claim to representing a social reality of people unified by language and by ethnic origin.” The concept of race, however, as a politically unifying marker, is a dangerous modern precedent, as Western Europeans and others have learned. Just as Chulalongkorn had included ethnic Shans within his new Siam, so another nation might include Thailand’s ethnic populations within her own borders. Thus a potential conflict with Thailand’s neighbors was created, even the possibility of a retrocession of territory according to race.

Let us pause here for a brief digression on the subject of Laos, the last of the Southeast Asian countries in our survey. Like the smaller European countries, such as Holland, Belgium or Switzerland, Laos is squeezed between two larger powers. (As the European countries are squeezed between France and Germany, so the Southeast Asian countries are squeezed between Thailand and Vietnam). Like Switzerland, Laos is landlocked and so historically has proven relatively inaccessible, partly because the Mekong, after it heads upstream from Cambodia, becomes non-navigable. Like Belgium, Laos shares a dialectical form of one of its neighbor’s languages (Flemish is a dialect of Dutch, as Lao, of Thai). Unlike Holland, Laos has never experienced power.

Due to its relative powerlessness Laos has been subject to a mixed hegemony; like Belgium and Switzerland it has various ethnicities (Belgium consisting of Walloon, French and Flemish populations, Switzerland, of Italian-, French-, Romansh- and Schweizerdeutsch-speaking contingents). Like that of Switzerland and Belgium, the very identity of Laos has required reaching internal accord among factions.

In a recent book, The Mekong, Osborne observes of 19th-century Laos’s “states”:

A small state along the upper reaches of the Mekong might be ruled by a “king” or a “prince” but still owe allegiance to one, two or even three more powerful rulers.

When [the French explorers] reached Luang Prabang, they found a state that accepted no fewer than three suzerains, the rulers of Bangkok, of Peking and of Mandalay.

There is, of course, a great difference between a multiethnic state and a state subject to foreign suzerains. The push-and-pull of ethnicities, even in modern-day Southeast Asia, like the often dramatic problems that define the domestic politics of the Middle East, can create disquieting instabilities. From a broader perspective, however, the fluctuations of populace and power in Laos or Cambodia are merely facts of life.

We have considered various political transformations that occurred during the modernization of Thailand: the establishment of a Buddhist state; its refinement and aggiornamento in the hands of successive, progressive monarchs; the king’s reestablish-ment of traditional ritual practices designed to insure the integrity of the kingdom. We turn now to the Thais’s concern for their ancient civilization. Since the start of the Bangkok period the court had been bent on retrieving the culture of the late Ayuttaya era, especially dramatic performances based on stories from the Ramakien (an adaptation of the Indian Ramayana) and the Inao tales (originally from Indonesia). Each successive monarch composed dramas based on episodes from these works.

Furthermore, Mongkut and Chulalongkorn had promoted the writing of history, “an important matter to be known clearly and accurately through study and teaching, as a discipline for evaluating ideas and actions as right or wrong, as good or bad, as a means to inculcate love of one’s nation,” the later king had said. Chulalongkorn emphasized that Thai history revealed the importance of the Buddhist model of kingship. “The Siamese king,” he asserts, “rules according to Buddhist morality.”

“Hence in Siam there has never been such a political event where the people were against the king. Contrary to what happened in Europe, Siamese kings have led the people so that both they and the country might be prosperous and happy; the people would never be pleased to have western institutions. They have more faith in the king than in any members of parliament, because they believe that the king more than anybody else practices justice and loves the people.”

“In the past,” he continues, “the king provided protection allowing the people to pursue the Buddhist path towards nibbana.” Now the king’s role was to bring progress.

“The Thai way of government is like a father over a son,” says Chulalongkorn. (We note the similarity with Chinese theory.) The result is a king “of the people,” he says, adapting the words of Abraham Lincoln, and “for the people,” he adds, “who derives his power from the people’s love.” Chulalongkorn, like Elizabeth I of England, identified the source of the monarch’s power as the love of the people. The Siamese elite, seeking principles of modernization, however, emphasized another strain of Chulalongkorn’s thought: by embracing the ideas of progress and history, “the technologies of mapping, colonial bureaucracy, law codes and military conscription,” thereby setting up a dialectic between progressive and conservative principles.

Moreover, the new men and women of early twentieth-century Siam “took up the ideas of nation, state and progress and recast them. They challenged the definition of the nation as those loyal to the king. They demanded that ‘progress’ be more widely shared. They redefined the purpose of the nation-state as the well-being of the nation’s members.” There followed political disruptions that subverted the institution of monarchy, as in the revolution of June 1932. But monarchy was to return, again under the influence of Buddhist ideology, which came to be associated with the cultivation and extension of good government and an educational system that had grown out of it. Other advantages of a monarchy based upon Buddhist thought came to be recognized.

For example, Buddhism was seen as a force for the resistance of Communism. “Equipped with bigger budgets and better means of communication, the militarized nation state believed that it could realize the imagined unity of a homogenous nation of Thai-speaking, loyal, development-pursuing Buddhist peasants throughout the national boundaries. . . . In December 1945 Prince Dhani Nivat . . . delivered a lecture on Siamese kingship attended by the young King Ananada Mahidol and his family. Dhani constructed a Sukhothai model of a naturally elected king who follows the ten royal virtues and “justifies himself as the king of Righteousness.” Royalists sought to support a return to the theory popular at the start of the Bangkok era.

According to this conception, kingship had been regarded as more representative than constitutional government. “Representatives of the people,” said one such Royalist, “are elected individually by groups of people, and they do not represent the whole people, as only the king can.” In other words, the Thais, though democratic in their form of government, came to be persuaded that power should come from the top downward. “Sarit declared that ‘The King and Nation are one and indivisible.’ He switched national day from the day of the 1932 Revolution to the King’s birthday. . . . He resumed the custom of presenting kathin robes to monks in the capital and later in the provinces. He revived the glittering royal barge processions. . . . He presented Buddha images, tablets and amulets to wat and offices during provincial tours.”

Buddhist principles

The Four Noble Truths

All life is suffering

The cause of suffering is desire

Suffering can be ended

The way to end suffering is the Noble Eightfold Path

The Eightfold Path

Right understanding

Right thought

Right speech

Right action

Right livelihood

Right effort

Right mindfulness

Right meditation

Buddhist practice (The Ten Paramis, or Virtues towards Perfection)

dana (virtue in alms-giving)

sita (morality)

nekkhamma (renunciation)

panna (wisdom)

viriya (perseverance)

khanti (forbearance)

sacca (truthfulness)

adhitthana (determination)

metta (all-embracing love)

upekka (equanimity)

Protestant theology

“The protestant view of the relationship between man and God is based on a series of antitheses defined in St. Paul’s Epistles: between law and gospel, flesh and spirit, works and faith, nature and grace, bondage and freedom, the first and the second Adam. It can be set out in a simplified form as follows. God created the first man, Adam, in his own image, a being in whom reason and will were perfectly integrated, who was free to exercise his reason and will as he chose, and capable of perfect obedience to God. God knew that Adam would exercise his choice wrongly, that he would fail the test of obedience, yet he allowed him full responsibility. Adam’s original sin, his disobedience to God represented by eating the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, has had calamitous consequences for the human race. Fallen man’s nature has become utterly depraved and corrupt. He is a mass of sin. He retains some vestiges of his original reason, but whereas Adam could freely and of his own efforts follow the dictates of his reason, the reason and will of fallen man are so vitiated that he can of his own efforts only choose to sin. Because of his sin man is condemned by God to a double death, the mortality of the body and the eternal damnation of the soul. Unaided, man is incapable of righteousness; he is in bondage to the law which demands righteousness but which he cannot fulfill. Hence he is justly condemned by God, since the corruption of his nature which makes righteousness impossible is the responsibility of the first man who freely disobeyed God.

“God’s justice, which punishes man for the sin of disobedience, is matched by his mercy, which forgives man. Yet his justice demands satisfaction. This is achieved through the mediation of God’s created gift to man, his Son, the second Adam, whose perfect obedience cancels the disobedience of the first Adam, and who gives himself as a sacrifice, thereby taking on himself man’s sin and redeeming him from damnation. The disobedience of the first Adam brought man death; the obedience of the second Adam brings man eternal life. Just as Christ takes on man’s sin, though he is himself sinless, so he imputes to man his righteousness, though fallen man is himself incapable of righteousness. God accepts Christ’s imputed righteousness or merits as man’s, and thus grants man salvation. This process of redemption, whereby man is released from sin and death and the impossible demands of the law, is the promise of the gospel.

“Man’s salvation is thus achieved not by his own efforts but by God’s grace. He is justified (i.e. accepted by God as righteous through Christ although in himself he is unrighteous) by faith alone, sole fide. [This is the crucial doctrine of Protestantism: Luther's conversion depended on his understanding of the phrase ‘the just shall live by faith,’ Romans 1:17.] Faith does not mean simply intellectual assent to the Christian creed, but trust that God will fulfill his promise. The man who is justified by faith is chosen by God for salvation: he is one of the elect. His faith is a gift of God. He is now adopted by God and regenerate, freed from his corrupt nature; through this change in his nature he has assurance that he is one of the elect. He is granted perseverance by God so that he can continue in a state of grace. The sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper are signs of God’s promise of salvation to him. The justified man through God’s grace cannot help producing good works and living a sanctified life, and hence he has evidence that he is of the elect. However, good works are the result not the cause of justification. Works contribute nothing to justification; works without faith do not justify a man, but faith without works is an impossibility.”

Having distinguished between the form of the above summaries (the first three in the form of lists, the last in the form of a narrative and theological commentary), I would like now to turn to a more general comparison of Buddhism and Christianity with the aim of illuminating similarities and differences between Buddhist and Christian states. Among the latter we include those western nations that regard the form of their government as a “Democracy,” for though they may see their governing principles as deriving from the rational philosophies of The Enlightenment, we all know the extent to which they are also motivated by Christian faith, however lax its current dispensation.

Let me begin with a number of rough-and-ready distinctions:

-

Doctrinal Buddhism: anatman (no-Soul vs. the Christian Soul); meditation (cp. Christian prayer); annica (impermanence); nirvana (cp. salvation)

-

Cultural Buddhism: religious iconography in sculpture, architecture, painting (contrast Protestantism and Islam; cp. Catholicism)

-

Political Buddhism: the devoted, selfless leader in whose wisdom we seek the proper course of political action or leadership thereto

-

Doctrinal Christianity: The Trinity, the teachings of Christ, The Crucifixion

-

Cultural Christianity: the medieval and Renaissance tradition

-

Political Christianity: Christians vs. infidels; The Christian Prince and his virtues; Church polity as proto-democracy; altruism; idealism

Having glossed the foregoing outlines, let me turn to other generalizations that may help us better to understand the similarities between Buddhism and Christianity. Both are systems of belief that have far exceeded their origins, in Bodh Gaya and Nazareth. Buddhism spreads, first, throughout India, then abroad, principally through its proselytizing force. Christianity and Islam also spread abroad by proselytizing force, and both have a history of even greater dissemination than Buddhism, often through the conversion of conquered populations and the pursuit of Empire.

Both religions center upon a soteriological figure, who comes to us bathed in light, and to whom the believer submits his prayer or meditation. Both focus upon suffering and a program for man’s release therefrom. Both emphasize the desirability of freedom, in Buddhism, freedom from samsara, in Christianity, freedom from the Old Testament law. Both are concerned with spirit: but whereas Buddhism defines itself in terms of a set of principles and a spiritual practice, Christianity defines itself in terms of a story of sacrifice and redemption and threatens the sinner with a terrible eschatology.

Whereas Buddhism is concerned with reconciling man with death, Christianity promotes the expectation of eternal life (though in this respect both religions also partake of one another’s doctrines). Whereas Buddhism focuses upon man’s own efforts at spiritual transcendence, Protestant Christianity focuses upon his salvation through God’s grace. On the other hand Catholicism, unlike Protestant Christianity, promotes justifi-cation through works; likewise, Buddhism emphasizes the accumulation of “merit” through works and ties the achievement of nirvana to discipline.

Unlike Christ who died young, nailed to a cross, the Buddha died in a state of nirvana, having attained to sanctity at the age of 80.

Buddhism’s meditative strategies represent a retreat from the world. Though the medieval monastic tradition of Christianity offers a parallel, Christianity’s model more commonly represents an active engagement with the world. In inactivity the Buddhist finds his nirvana; in works, or in God’s grace, the Christian finds his.

How then explain the efficacy of the Buddhist king in Thailand? Perhaps by recourse to the Christian theory of the two ways: the via contemplativa and the via activa. For the Thai king, from the wisdom acquired through meditation, takes action.

In so doing has his Buddhist theory of political action surpassed the Christian principles of prayer and engagement, or are the two systems analogous? Perhaps it would be best for me to leave such judgments to the audience.

Let us turn finally to the more complex question of Christianity’s effect on the political development of Western Europe in relation to Buddhism’s effect on the political development of Southeast Asia. First, Christianity:

Was Europe less humane under the Romans and the Goths than under the Holy Roman Empire and subsequent sovereign Christian states, in Iberia, in the British Isles, in France, Germany, Italy and the smaller nations? Though one might like to think so, the history of the crusades, of the religious wars of the Renaissance and the 17th century, of the Napoleonic conquests, of the atrocities of World Wars I and II certainly cast doubt upon such a generalization. They also question whether the pacific teachings of Christ eventuate politically and militarily in peace rather than war.

On the other side of the equation, let us consider Buddhism’s role in the world, here in the light of an exchange between a questioner and a famous Thai teacher:

Q: The provinces that surround your temple have been deeply involved in the traditionalist vs. communist political struggle common to Southeast Asia. Do you see a role for monks or teachers like yourself in this struggle?

A: One way that the Buddha’s teaching has survived for 2500 years is by monks not taking sides in politics. The Dharma is above politics. Our temple is a refuge from the battleground, just as the Dharma is a refuge from the battleground of desires. Both sides in these fights may have legitimate complaints, but the true peace is an inner one that can only come through the Dharma. For monks and lay people alike, security comes from the Dharma, from wisdom which sees the impermanence of all things in the world.

(“Recollections of an Interview with Achaan Jumnien at Wat Sukontawas, Surrathani, Thailand,” by Jack Kornfield, in Living Dharma)

Because it focuses upon the individual (or so we have said), Buddhism lends itself to the institution of Democracy. In this it is similar to Christianity. But because, like Christianity, Buddhism, also has, we might say, an authoritarian streak, historically it has lent itself to the institution of kingship, especially in Myanmar, Thailand and Cambodia, countries in which the king is regarded as a Buddha, as an avatar of Vishnu.

But we might also reformulate these generalizations so as to argue that the double European traditions of Catholicism and Protestantism lend themselves, first, to the power of pope and king, later, to the power of the people; that the double Southeast Asian traditions of (a) individual salvation (b) through a figure of authority have made the tradition of rule by a Buddhist king more plausible and effective.