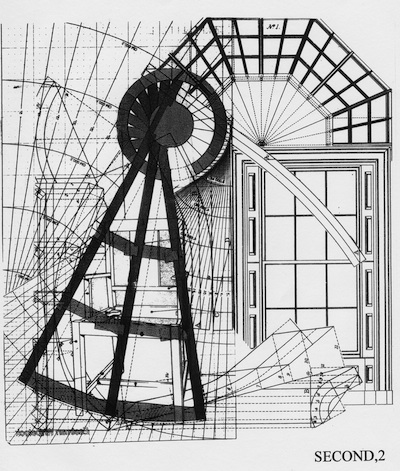

Illustration by Denis Mizzi

2

Alexandroupoli nightlife: “Chaos,” two black doors, “Closed.” “I am Odysseus, son of Laertes” (Homer). Their handles not responsive to being pulled. “Known above all men for crafty designs.” “Artakie,” a cavernous one-room club, its sign reading “Privé,” its décor in black and white, two silver-clad pillars rising from a central well. “And my fame goes up to the heavens.” Three candles are burning atop the bar, it not clear why the electricity is off. “I am at home in sunny Ithaka.” At any rate, the music has been extinguished along with the lights. “There stands a tall mountain, leaf-trembling Neritos, about it other islands lie close to one another.” Around a circular table sit three women. “Doulichion, Same and wooded Zakynthos.” Now three men draw up chairs to take seats in amongst them. “But the island that I call mine lies low and away, last of all upon the dark water.” The relationship of the three men to the three women is obscure. “The other islands face the east and the sunshine.”

“Chaos,” the club visited earlier, now has lit its neon sign. “Ithaka is rugged but a good nurse of men.” Preceding author, a man enters with a black bottle of wine, then quickly reversing his course exits. “For my part I cannot think of any place sweeter on earth to look at.” Within the darkness of “Chaos” the electronic sound system pulsates. “For in truth Kalypso, shining among divinities, held me in her hollow caverns, desiring that I be her husband.” Having also passed several coffee shops with no lights burning, author finally understands why these interiors are darkened: “And so likewise Aiaian Circe the guileful detained me, but never could she persuade my heart.” In a town of but 37,000 residents, it may not be desirable that others know one’s nighttime identity or whereabouts. “So nothing is more sweet in the end than country and parents, even though one live far away from them in a fertile place.”

Along an up-market avenue, the Café Del Mar is also darkened. “In an alien country, far from ones parents.” The Café Daily, however, which is advertising “Honey-Sweet Fruit,” is brightly, even seductively lit up. “Come, I will tell you of my voyage home with its many troubles.” The Barracuda Club, half-lit, has a whole wall filled with video games. “Which Zeus inflicted on me as I came ashore.” A patron is engaged with “RockSkyll,” a brutal Japanese game. Author perambulates Alexandroupoli’s central streets, past bars patronized by middle-aged men, their circular tables covered with green baize for gambling; past a darkened park, its playground equipment painted in outrageously bright red, yellow and blue; past a street fronting the sea, whose waves lash up over the embankment toward a pub called “Aeolus.”

“From Ilion the wind took me and drove me ashore at Ismaros

in the land of the Kikonians. I sacked their city and killed

their people, taking with me their wives and many possessions;

we shared them out, so none might go cheated of his proper

portion. I favored a light-footed escape, and strongly

urged it, but my foolish companions would not listen to me . . .”

“Simplicius, doubtless quoting from a version of Theophrastus’ history of early philosophy, identifies in Anaximander some other apeiron nature, from which come into being all the heavens and the worlds in them. And this source of coming-to-be is that into which destruction too happens, he says, according to necessity, since, he adds in his most poetical description of the matter, they pay penalty and retribution to each other for their injustice according to the assessment of time.

“Meanwhile the Kikonians went and summoned other

Kikonians, their compatriots from the inland country, more

numerous than themselves and better men, well skilled in fighting,

men with horses, but knowing too at need the battle

on foot. These arrived at early morning, like flowers in season

or leaves, and the luck that came our way from Zeus was evil,

to make us unfortunate, and give us hard pains to suffer.”

The wind picks up. Surrealistically the surf gleams under large white streetlights. We pass the “Amis Café.” In the grid of the sidewalk holes have been dug, deep rectangular trenches large enough for men.

“Both sides stood and fought their battle there by the running

ships, and with bronze-headed spears they cast at each other;

as long as it was early and the sacred daylight increased, so long

we stood fast and fought them off, however outnumbered.”

But some, as Diogenes Laertius asseverates (citing Eudemus in his history of astronomy), consider that Thales of Miletus was the first to study the heavenly bodies and foretell eclipses of the sun and solstices. “And when the sun had gone to the time for unyoking of cattle, / then at last the Kikonians turned the Achaians back and beat them, / and out of each ship six of my strong-greaved companions / were killed, but the rest of us fled from Death and Destruction.” For which reason, he adds, both Xenophanes and Herodotus express admiration, and both Heraclitus and Democritus bear witness for him.

“From there we sailed farther, glad to have escaped from Death, but grieving still at heart over the loss of our dear companions.” For when they reproached the great philosopher of Miletus concerning his poverty, says Aristotle, as though philosophy were no use, it is said that he, having seen through study of the heavenly bodies that there would be a large olive-crop, raised a little capital, while it was still winter, and paid deposits on all the olive presses in Miletus and Chios, hiring them cheaply because no one bid against him.

In the rectangular plots, dug in the sidewalk, trees have been planted. We pass the “Alexandrian Coffee Shop,” as ahead of us looms the famous lighthouse of Alexandroupoli, circulating its light high above the city. We pass the “Akropon,” the central square in front of the harbor; we pass the “Step In.” And the voice of Odysseus resumes: “Even then I would not suffer the flight of my oar-swept vessels / until a cry had been made three times for each of my wretched companions, who died there in the plain, killed by the Kikonians. When the appropriate time came there was a sudden rush of requests for the presses; he hired them out on his own terms and so made a large profit. The clock tower reads 5 minutes to 10, an hour slow.

Sunrise panorama, Alexandroupoli. It is principally the sea, sea birds, and other birds that appear in motion. A solitary fishing boat makes its way out the harbor’s mouth onto the milky, pink-blue surface of the early Aegean. In a striped parking lot a hundred birds, all white, are taking their morning stroll. Yellow-helmeted, a green-jacketed motorcyclist enters through the gate and continues down the jetty a quarter of a mile, half a mile, three-quarters of a mile, a mile, to the end of the pier. In the process he scares off a flock of birds, which drift gorgeously across the inner harbor. Now he returns. At the dock a cruise ship waits for what one supposes will be an evening departure for Lindos, in the direction of Samothrake, on to Mytilini, Samos, Kos and perhaps Rhodes. The motorcyclist skirts a trailer truck set to unload its cargo, smaller vans, a red sedan. His passage creates the only noise the length of the causeway. At last he exits through the gates that he had entered. His ride apparently has been for pleasure.

Now, as he proceeds on westward, past cranes unloading ships, other traffic moves eastward. A fishing boat, having left behind the last stones of the jetty, also turns toward the east. A train’s horn sounds, as it arrives from the west to proceed through Alexandroupoli, its white headlight still shining in the late dawn. Eastward down the seaboard avenue heads a red Mercedes truck. Within ten minutes the sun has evolved from a red ball into a golden disk. It was in Ionia that the first completely rational attempt to describe the nature of the world took place (Kirk and Raven, The Presocratic Philosophers). Through the mist it begins to illuminate the outline of Samothrake, imposing but nonetheless vague and mysterious. There, material prosperity and special opportunities for contact with other cultures — with Sardis, for example, by land, with Egypt by sea — derived from the principal tradition of culture and literature that dates from the age of Homer.

We are easing out of the harbor to leave Thrace behind. A string of yellow-orange lights beads the horizon. The surface of the sea is nearly pitch black. All day long Samothrake has been hidden. Then within the space of a century Miletus produced Thales, Anaximander and Anaximenes, each dominated by the assumption of a single primary material, the isolation of which was considered the most important step in any systematic account of reality. Within two hours we will skirt her, according to the map, along her western, least inhabited, flank. This approach was clearly a development out of the genetic or genealogical view of nature as exemplified by the Hesiodic Theogony. In all likelihood we will then sail between Samothrake and Gökçeada, a large Turkish island not far from the Dardanelles. Before long, on our right, Lindos should be visible, visible, that is, if it be not still pitch black.

After the great Milesians, however, the attitude was moderated or abandoned. At about the same time we will sail beyond the island of Tenedos, the modern Turkish Vozcada. Xenophanes is here treated among the Ionians, but in fact he does not fit into any general category. Before sunrise we will dip beneath a jutting peninsula of Turkey. Born and brought up in Colophon, and strongly aware of Ionian ideas (more so, apparently, than was Pythagoras), he moved to western Greece and only incidentally took up the details of cosmogony and cosmology. Here we will turn ever farther eastwards, past Mithymna, the second largest city of Lesvos, continuing on to Mytilini, her principal port, where we will finally make landfall. Meanwhile, in Ephesus. On March 10 our large ship has very few passengers, though author’s cabin is occupied by four of them. The individualistic Heraclitus out-stepped the limits of material monism. Seated in the lounge, he contemplates whether or not to stay up for two more hours simply to say that he has peered out into the blackness at Samothrake. While retaining the idea of a basic (though not a cosmogonic) substance, he discovered the most significant unity of things.

Will we be able to discern the mighty peak of Mt. Fengari, where, according to Homer, Poseidon stood and watched the Trojan War? It was a unity which he assumed without question lay in their structure or arrangement. Not far from this peak, at Paleopolis, lies the sanctuary of the Great Gods. Here exists a parallel with Pythagorean theories in the west of the Greek world. “Samothrake,” says the guidebook, “was first settled in about 1000 B.C. by Thracians, who worshipped the Great Gods, a cult of Anatolian origin.” Pythagoreanism in turn produced the reaction of Parmenides, and for a time western schools were all-important. The lounge’s television set is occupied with a Greek soap opera, ignored by most of the passengers. But the materialistic monism of Ionia re-asserted itself, at least to a certain extent. By all, that is, but a single, 30-year-old man, balding, who has taken a seat in front of the TV. In the compromises of some of the post-Parmenidean systems.

“In 700 B.C. the island was colonized by people from Lesvos,” says the guidebook, “who absorbed the Thracian cult into the worship of the Olympian gods.” Even all-powerful Cronus himself was seized by a great fear: he was no longer certain that his rule would endure forever, for he now remembered his father’s curse with horror and worried lest his own children rise against him as he had done against Uranus (Menelaos Stephanides, The Gods of Olympus). On the wall, behind the reception desk stands a four-foot by three-foot photograph of a Byzantine angel, its wings in silver, likewise its crown and tresses. And so he took a horrible decision: he ordered his wife, Rhea, to bring him every child she bore, and each time she did so he swallowed it alive. For the past two minutes the television soap opera has been exchanging reverse shots. In this way he consumed five infants that Rhea bore him: Hera, Demeter and Hestia, Hades and Poseidon. Of a woman in shoulder-length tresses and her boyfriend in black leather jacket.

Rhea was now with child again and at her wits’ end. Alternately the man and woman have been arguing and necking. She could not think what she might do to save the infants. They run into one another’s arms. “The principal deity among the Great Gods,” says the guidebook, “was the Great Mother, Alceros Cybele, long worshipped as a fertility goddess.” Accordingly she sought out her parents, Uranus and Mother Earth, who advised her to give birth to her baby on Crete, in a cave on Mount Dicte, well hidden among the forests. Two girls in their early twenties from Lesvos, met by author on the dock in Alexandroupoli, are ordering snacks. In this sacred cave, Rhea gave birth to her child, entrusting it to the nymphs of the forest who had helped bring the baby into the world. Having been served at the counter, they are now deciding where they should sit. “When the original religion became assimilated into the state religion.” She returned secretly to the palace of Cronus. “The Great Mother merged with the Olympian female deities, Demeter, Aphrodite and Hecate. And began to cry out that she had been seized by birth pangs.

The television screen shows a little girl, a mother figure exhorting her from behind a red veil. “Hecate, the last of these, was a mysterious goddess, associated with darkness.” The two girls from Lesvos, having first seated themselves at some distance, have now settled in directly before the TV set. The fearsome Cronus believed that his wife really was in labor, and he did not fail to remind her once again of his cruel orders: A number of young men, soldiers on furlough, or so it would seem, have also taken seats at two separate tables, between which they converse, their brush cuts bobbing with earnest animation. “Get it over with, woman, I can’t bear your screaming.” These four guys are now joined by four girls. “And bring me the child as soon as it is born.” And with these heartless words he left Rhea’s room.

“One famous visitor to Samothrake, who did not come to be initiated, was St. Paul, who dropped in on route to Philippi.” Three single guys in their late twenties, all looking a little depressed, lounge in desultory fashion, one over a cup of coffee, one over a cigarette, one over a bottle of beer. “Other deities worshipped on Samothrake were the Great Mother’s consort, the virile young Kadmilos, god of the phallus, who was later integrated with the Olympian Hermes.” Two guys, one in white sweater, one in black tee shirt, sit at a table together. “Among the gods at Samothrake were the demonic Kaberoi twins, Dardanos and Aeton, who were later integrated with Castor and Pollux, the sons of Zeus and Leda.” A little boy and a little girl have joined them. “These twins were evoked by mariners to protect them against the perils of the sea.” The little girl is dressed in red, the little boy in green.

As soon as he had gone, Rhea took a stone, wrapped it in cloth so that it could not be seen and a little later presented it to her husband in place of the child. “‘Cloud-gathering Zeus drove the North Wind against our vessels,’” says Homer (Odysseus), as he concludes this stage of his narrative, “‘in a supernatural storm; there huddled under the cloud scuds land and the great water alike.’” Cronos, suspecting nothing, swallowed the stone with satisfaction. “‘Night sprang from heaven.

“Our ships were swept along yawing with the current; the violence

of the wind ripped their sails into three and four pieces. These then,

in fear of Destruction, we took down and stowed in the ships’ hulls,

and rowed them on ourselves until we had made the mainland.

There for two nights and two days together we lay up,

for Pain and Weariness together were eating our hearts out.”

The baby that escaped was none other than Zeus.

We arise before the sun to the pearly waters of the Aegean, silver on green on blue. In those difficult years, when the reign of Cronus had loosed Evil upon the world, the birth of Zeus seems like the birth of Hope. Over the horizon of shaded grey appears rosy-fingered Dawn. And his survival like the beginning of the struggle for a better world. The pink sun suffuses a grey cloudbank, impregnating it with light. All the deities of Crete hastened to the support of this baby that had first seen the light of day in the cave on Mt. Dicte. Eos gives shape to the indeterminate. It was as if something told them that his were the hands that would free the world from bonds. Or, as Homer has it,

“When the fair-haired Dawn in her rounds brought on the third day,

we, setting the masts upright, and hoisting the white sails on them,

sat still, and let the wind and the steersmen hold them steady.”

But the story has only begun, for in Homer’s words spoken by Odysseus:

“I would have come home unscathed to the land of my fathers,

but as I turned the hook of Maleia, the current and the North Wind

beat me off course, and drove me on past Kythera.”

Our story too is but just under way: A bird soars up and out from the coast, as a tiny fisherman’s boat crosses between us and the mountain. The sky continues to warm, like embers, till suddenly in the notch between two little peaks a bright pink begins to glow roseate, then red, the grey cloudbank seeming to catch fire. Illuminated wavelets dance atop the grey-green base of a sea half hidden in cloud, as the lower semicircle of the sun makes its appearance on the horizon. A near ground skein of white pufflets drifts across a beige cloud. A gull flaps to keep up with us, its entire body reddened by the rays of the sun. Next, a staged opening: within a break at the center of the cloud mass the ball of the sun appears, its flame obscured but its rays emitted, yellowing, through the newly penetrated aperture. A bird crosses this field and is instantly turned to gold. Now, as in a second sunrise, the upper aureate semicircle emerges through the opening, as higher yet an even larger hole appears, encircling it a golden fleece of many-textured clouds.

Odysseus leaves home for the Trojan War

Ostensibly to avenge the rape of Helen

But in fact to escape Anticlea and Penelope.

His mother poses the greater problem,

For only with her death can he return.

She dies of longing for Odysseus,

Having spent a lonely life with Laertes,

Who, in the end, withdraws altogether.

Penelope has lost her husband by seeking

To bind him in a marriage he rebels against.

For he prefers the magical binding of Circe

To hers, Calypso’s libertine sway to

Circe’s, and so indicates by

Spending seven years with the nymph.

At last he returns, but in disguise.

This time Penelope chooses a stranger,

Making a truly exogamous match.

To regain his wife and insure himself

Against Menelaus’ fate, Odysseus

Brutally slaughters all competition.

Nevertheless, he will leave again.

With Lesvos now in sight, author makes his way onto the deck for further observation. To the west rises her castle, to the east the white buildings of her harbor, mounding on up the mountainside. Forest-encrusted, the mountain itself ascends higher. As Homer continues to double himself in Odysseus, so the god Hermes enters to double them both: “Where are you heading, poor fellow, all alone,” he asks, “and in strange country?” From the vantage of the deck her valleys and small villages are also visible. “Off to see Circe and her herds of swine, no doubt,” he continues. “I warn you, it’s pigs she’s turned your comrades into, and a pig she’ll turn you into, too, when you try to set them free.”

On the shore as we approach gleam individual houses. “But I will save you from the terrible fate she has in store for you.” The sun is now behind us. “Do you see the plant that’s growing from the rock? It will protect a man from any evil. First you must listen, though, while I tell you of all her cunning tricks and how you must respond to them.” As our ship turns, we plow an aquamarine course through the grey seas. “To start with, she will give you porridge in which she has sprinkled some of her magic herbs.” Seagulls are following in our wake. “But they will not take hold on you, thanks to the powers that this plant wields.” As we complete our 180-degree turn, great clefts struck out of the mountain come into prominence. “Next she will strike you with her wand.” The shore looms even closer. “You must draw your sword and threaten to fall on her and kill her.” Individual houses bay out like architectural models. “In her terror, she will first try to soothe you with sweet words, then offer to let you sleep with her.” The ship like a goddess progresses toward the port. “Do not refuse, if you wish to rescue your companions.” Having at last made contact with the dock, we enter into the process of disembarkation. “But before you do so, make her swear a solemn oath by all the gods that she will do you no harm.” Gulls float alongside the descending passengers. “And will not rob you of your manhood when you lie down by her side.” Behind us, beside us, they skim the surface of the sea.

Son of Zeus and Maia (the daughter

Of Atlas), brother to Apollo, whose cattle

He steals the day he’s born. Returning

Home he strings the tortoise shell.

Charmed by the lyre, Apollo forgives him.

Conductor of souls, messenger, he replaces

Iris, displaces Apollo,

Misplaces property; is, like

Odysseus, prudent, cunning, mendacious.

Unlike O., he is also magical.

Gives to Civilized Man his most

Needed instruments: the alphabet,

The numbers, astronomy, music.

To Commercial Man: weights and measures,

Cultivation of the olive tree.

To Poetic Man, who in Arcady

Worshipped him, his sacred things:

Palm tree, minnow, the number 4.

In broad-brimmed hat, wand

Serpent-entwined, sandals wingèd,

He is secret, hidden, invisible.

Among the most important representatives of artistic and intellectual life who worked in Lesvos are (Eleni Palaska-Papasthati): Terpandrus, who transformed the four-string into the seven-string lyre. Having said this, the wing-footed god pulled the plant from out a crevice in the rock. Alcaeus, one of whose great admirers was the Roman poet Horace. Its pure white flowers. Sappho. Had a black root. Legend says that she fell into the sea from the precipitous cliffs of Lefkata Cape, in Leucadia. So tough that no human hand could ever dislodge it. Theophrastus, the father of botany, Plato’s and Aristotle’s disciple. The gods, however, can do all things. Who taught in the Peripatetic School.

In Mytilini we begin with the port. Others say that the earth rests on water (Aristotle, De Caelo). Where a tall yellow crane is unloading gravel from the grey hold of the Alhajjehhend. For this is the most ancient account that we have received, which they say was given by Thales the Milesian, that it stays in place through floating like a log or some other thing (for none of these rests by nature on air, but rather on water). The crane has written on its side, in Greek letters, “Limeniko Tameio Lesboy.” The near-eastern origin of Thales’s cosmology is indicated by his conception (Kirk and Raven) that the earth floats or rests on water. The crane is depositing the gravel, huge scoopful by scoopful, into the bed of a grey truck on whose front is a nude pin-up in black silhouette. The story of Eridu (in its earliest, seventh century B.C. version) says that in the beginning “all land was sea.”

Kalypso gave Odysseus a great ax that was shaped for his palms and headed

with bronze, with a double edge each way, and she fitted inside it

a very beautiful handle of olive wood, well hafted;

then she gave him a well-finished adze, and led the way onward

to the far end of the island where there were trees, tall grown,

alder and black poplar and fir that towered to the heaven

but all gone dry long ago and dead, so they would float lightly.

“Then Marduk built a raft on the surface of the water, and on the raft a reed-hut which became the earth.” The nude is large-breasted, thin-armed, narrow-waisted, amply-buttocked.

But when she had shown Odysseus where the tall trees grew, Kalypso,

shining among divinities, went back to her own house

while he turned to cutting his timbers and quickly finishing his work.

Next to the Alhajjehhend is tied up the Elena.X, her black hull deep in the water. An analogous view is implied in the Psalms of David, where Jahweh “stretched out the earth above the waters,” “founded it upon the seas, and established it upon the floods” (Leviathan is also an analogue of Tiamat).

He threw down twenty in all, and trimmed them well with his bronze ax,

and planed them expertly, and trued them straight to a chalk line.

At that time the shining goddess Kalypso returned, bringing him

an auger, and he bored through them all and pinned them together

with dowels, and then with cords he lashed his raft together.

Against this profusion of parallel material (from the east and south-east) for the waters under the earth there is no comparable Greek material apart from Thales. Across from the grey truck with the nude pin-up is a truck painted half a dozen colors, its hood maroon, its front fenders green and yellow, its doors orange with turquoise panels, its bed deep blue. Above either window, atop a purple sunscreen, stand two white figures of Mickey Michelin. “Sophia” reads the windscreen. Generally, life in Lesbos, despite economic development and tourism, is still keeping many traditional elements and together with them the kind-heartedness and calmness of the good old days (Palaska-Papasthati). Past a dangling heart with eyes and mouth, with two white hands and pink legs, sits, behind the driver’s seat, a mother tiger surrounded by half a dozen cubs. Across from this scene, but still within the commercial harbor, a shop advertises “Texnologos Geoponos.” Along with a display of Dutch flower bulbs and begonias are Stihl Rotomatic chain saws, Yanmar roto-tillers, seeds for dahlia, gladiolus and canna. Next door two woven-seated chairs have been set back to back at an interval of four feet, a stick laid between them, from which squid have been slung to dry.

As we turn the corner, the inner harbor opens up to view. The ship that we had arrived on is still loading for its next departure. A Navy ship, marked “P-99,” is moored behind it, beyond it, in turn, the commercial establishments, restaurants and hotels of Mytilini. A sign on the street reads “Port,” two arrows extending out of it; on one has been lettered “Kalloni,” on the other, “Airport.” We traverse the shade into the sunshine to regard an undistinguished classicized building, in square pilasters and Corinthian capitals, such as one would see in any other part of the western world. “Nomarchia Lesboy” reads a marble inscription at its corner.

If Thales (Kirk and Raven) earned the title of the first Greek philosopher mainly because he abandoned mythological formulations, Anaximander is the first who made a comprehensive and detailed attempt to explain all aspects of the world of man’s experience. A pollarded tree, each of whose stumps has put out a new branch, has had these branches tied together at its summit, making of the tree’s branches a sphere. Eratosthenes says (Strabo, the Casaubon) that the first to follow Homer was Anaximander, and that he was the first to publish a geographical map. We continue on down a sunlit esplanade. After him (says Agathemerus) Hecataeus the Milesian, a much-traveled man, made the map more accurate, so that it became a source of wonder. As we approach the clustered buildings at the harbor’s far end, we come upon a kiosk selling international papers: French, American, British, German, Dutch. The buds of a huge tree behind it are turning to leaves. Anaximander (Kirk and Raven) produced a circular plan in which the known regions of the world formed roughly equal segments. In a small park behind the kiosk has been placed a globe circled by three boys, naked, standing with their backs to the world and holding one another’s hands. His empirical knowledge of geography was based in part on seafarers’ reports, which in Miletus, the commercial center and founder of colonies, would have been both accessible and varied. Atop the sphere rest three pigeons in bronze. The philosopher himself was said to have led a colonizing expedition to Apollonia (the city on the Black Sea). Closer inspection reveals that the three “boys” are actually men, one African, one Caucasian, one Oriental. Otherwise his only known foreign contact was with Sparta.

We pass another classicized facade from which a flagpole projects. On it flutters the blue European flag with its circle of stars. “Dimotiki Vivliothiki,” the building’s inscription reads. For Anaximander the main opposites in cosmogony were the hot substance and the cold substance, flame or fire and mist or air. We turn to promenade the commercial street. Thus he distinguished himself from Thales. Set back one block behind the harbor street and parallel to it. For whom water had been the sole primary substance.

Anaximander (Augustine) thought that things were born not from one substance, as Thales thought from water, but each from its own particular principles. A tourist shop is displaying postcards, one of which identifies as the Archangel Michael the silver figure whom author had observed behind the ship’s reception desk. These principles of individual things he believed to be infinite. This unpaved street is all business: And to give birth to innumerable worlds and whatsoever arises within them. Fish shops offer this morning’s catch, each variety labeled in Greek. (He believed, says Censorinus, that originally men were conceived inside fish-like creatures.) Huge cheeses fill the window of a grocery store, beans in reinforced plastic bags on the street outside it; beside them, a red plastic bucket of olives, a blue scoop for lifting them out; beside them, potatoes, onions and greens. And those worlds, he thought, are now dissolved, now born again. A bookstore displays school supplies: texts, notebooks and pens; encyclopedic books about Egypt, fish and primitive man. According to the age to which each is able to survive. In a refrigerated case a bakery is offering special Greek sweets.

Next door a home appliance store has set out on a table modern electric irons, all in white, but trimmed in sea green, leaf green, sea blue, cloud grey. It is clear (Kirk and Raven) that if Anaximander thought that the sea would dry up once and for all this would be a serious betrayal of the principle that things are punished because of their injustice: for land would have encroached upon sea without suffering retribution. Across the street a white-jacketed butcher is cutting meat for an obstreperous matron. Our interpretation of Fragment 112 as an assertion of cosmic stability may, however, be wrong. Sausages hang from hooks before him, as he labors to satisfy her requirements. Could the drying up of the earth be the prelude to re-absorption into the Indefinite? A plucked chicken hangs by its yellow feet. This it could not be, since if the earth were destroyed by drought such an event would implicitly qualify the Indefinite itself as dry and fiery, thus contradicting its very nature. Two doors down a bridal store is showing a dark-skinned manikin with long, curly black tresses dressed in a white gown.

The principle of the fragment could, nonetheless, be preserved if the diminution of the sea were only one part of a cyclical process: At a jeweler’s shop one window has been devoted to enormous fabric butterflies, painted in extravagant colors. When the sea is dry a “great winter” (to use Aristotle’s term, which he may have derived from earlier theories) begins, but eventually the other extreme is reached wherein all the earth is overrun by sea and turns into slime. Black, silver and turquoise; yellow-green, with purple antennae, orange spiraled eyes, and magenta legs. That this is what Anaximander thought is made more probable by the work of Xenophanes, another Ionian of the next generation, who postulated cycles of the earth drying out and turning into slime. Sunlit side alleys flow into the narrow, darkened shopping street. Xenophanes was impressed by fossils of plant and animal life embedded in rocks far from the present sea and deduced that the earth was once mud. Coffee beans are being roasted on the street and circulated by an electric swivel. But he argued not that the sea will dry up even more but that everything will turn back into mud. A photographic studio is showing romantic scenes: Men will be destroyed. Lovers embracing on a sandy beach. Then, he says, the cycle will continue: Santorini by night. The land will dry out. Venice by day. And men will be produced anew.

Many important scholars, writers and artists (Palaska-Papasthati) were born in Lesvos: A girl stands in a shoe shop doorway, smiling. Such as Stratis Myrivilis. Here alleyways communicate as well with the harbor. Argyris Eftaliotis. They are lined with more shops and small cafés. Yiorgos Iakovidis. Repairs are being undertaken, a new neon sign installed. Stratis Eleftheriadis. As well as new construction. And Theophilos. At the point that we have reached the whole street has been torn up, so that men may work beneath its surface.

A huge black crane is picking up the cylindrical concrete sections of a new drainage system from a green-bedded truck. Anaximander says (Pseudo-Plutarch) that the earth is cylindrical in shape, and that its depth is a third of its width. A yellow backhoe with blue hydraulic arms breaks the trench open. Its shape is curved, round, similar to the drum of a column. We continue on down the shopping street, which has metamorphosed into a new district. Of its flat surfaces we walk on one, while the other is on the opposite side of the earth. We have reached the town’s clock tower and turn into a passageway that leads back into the harbor.

It is curiously demure, even secretive, for we have entered into a residential area, its houses interspersed with shops selling computers, stationery, ladies underwear. Still others are cluttered with centuries of accumulation. Suddenly we arrive at an entertainment district of pool halls and video game parlors. A second turning brings us back to a view of the harbor. Another right takes us by the major cafés that line its western end: “Hot Spot,” “Marush,” “Papa Gallino.” On the sidewalk a little girl in a blue skirt embroidered with silver stars, a yellow long-sleeved blouse with creamy gauze supersleeves is stripping multi-colored confetti from her body. The heavenly bodies come into being as a circle of fire separated from the fire of this world and enclosed by air (Hippolytus interpreting Anaximander). As author passes her, the little girl smiles broadly, revealing two missing front teeth. The heavenly bodies show themselves through breathing-holes, certain pipe-like passages. Now she swirls her skirts and begins to dance. Accordingly eclipses occur when these passages are blocked up. Along the waterfront a clown, his yellow shirt covered with blue and red stars, gazes out. The moon is seen now waxing, now waning. He has been sculpted in plaster of Paris. According to the blocking or opening of the channels. About his chest a sign advertises “Karnivali.” Fully three-dimensional. The circle of the sun is 27 times the size of the earth, that of the moon 18 times. His back side nonetheless duplicates his front side. The sun is highest, the circles of the fixed stars lowest. Except that his front face smiles and his back face frowns. On both sides dancing figures advertise the Carnival.

“‘Let’s give her a shout, whoever she is,’ one of them suggested,” says Homer’s famed narrator, Odysseus. In a rather desultory public space stands a statue of Sappho. “They called out and she ceased her singing and came to open the door.” On its marble base someone has penciled in black, “Stop Fasism [sic].” “It was Circe herself, the lovely but imposing goddess.” The figure of Sappho faces out toward another figure, this one a goofily cartoon-like papier-mâché sculpture, his head a quarter the height of his body. “She invited them in.” He represents a middle-aged Greek workman. “All entered except Eurylochus, who feared some evil.” In his left hand he holds a bottle, in his right a cup. “Politely she begged them to be seated.” Dressed in a blue smock, he kneels barefooted on the plaza, a sign about his neck. “And offered them a porridge of cheese and honey mixed with flour and wine.” “Karnivali Demoi Mytilinis,” it reads. “But into it she slipped some magic herbs.”

Author takes seat outdoors at the “Kirke,” the figure in question represented in a whited face, with black eye shadow, black eye liner underlined in red. “Eurylochus waited in vain for his companions.” Her hair, wild and full, is depicted in strokes of fiery red and black. “When he realized some great harm must have come to them, he took to his heels, hoping that at least he himself could be saved.” Her portrait has been painted on a piece of driftwood and tacked above the café’s three-paned door. “By the time he reached the ship he was half dead from terror, trembling so violently that not a single word would pass from his lips.” On the building’s pink side hangs a black slate, on which have been chalked in white Greek letters the words “Kiriaki,” “Kolasi,” “Parte Maski.” A double of the witch has been outlined in blue. “Anxiously we pressed him, till at last he found his voice again.”

A nearly naked, full-figured female, dressed in triangular panties and a slim bra, has been sketched in pink beside the door, two ghosts on either side of her indicated in yellow. “He told us that while out scouting they had come to a tall palace where a terrible witch dwelled, and that his comrades had simply vanished the moment they entered.” Within the café we glimpse decorations for Carnival. Back outside, seated at a table set with a full carafe of wine, a red-haired, middle-aged woman in black leather jacket pauses to slap a passing boy teasingly. Out of her bag she withdraws more party ornaments, arises and enters the club. From the central point in the ceiling, visible once more as the door opens, descend net-like skeins of crepe paper, orange interwoven with blue, to which have been attached hearts in the shape of arrows or phalluses. To another net of black and yellow paper pink phallic hearts have been attached.

“As soon as I heard this I buckled on my sword, picked up my bow and ordered Eurylochus to come along and point me out the way.” At the end of the chamber hangs a ceramic mask, doubled in the mirror to whose frame it has been nailed. “But instead of obeying he threw himself at my feet and started begging not to go:

“Illustrious, do not take me against my will there. Leave me

here, for I know you will never yourself return, nor bring back

any companions of yours. Let us rather make haste, and with those

who are left, escape, for still we may avoid the day of evil.”

In the past, Lesvos universally considered the wedding an important and festive event (Palaska-Papastathi).

So he spoke, and I answered again in turn and said to him:

In many villages they covered the bride’s head with a red cloth.

“Eurylochos, you may stay here eating and drinking, even

where you are and beside the hollow black ship.” Whereon they cut

the cake and offered it to the guests. “Only I shall go.” To the groom’s

house the bride was required to convey a large circular

baking pan of baklava that she had made herself.

“A strong compulsion is upon me.” Here she was required to cut

from its center a round piece and present it to her mother-in-law.

And so I spoke and started up from the ship and the seashore.

From the Dutch edition of Lesbos: History, Folklore, Archaeology, Excursions (the only version available at the news stand) author learns that several important events in the Homeric epos occurred here. In the early years of the Trojan War, says its author, Odysseus slew the king Philomelidis of Lesbos, an island that Achilles had also visited a number of times, once to carry off his prized Briseis. The seven brides that Odysseus, in Iliad IX’s embassy to Achilles, tells the sulking hero that Agamemnon will give him as reward for returning to battle, are also identified as coming from Lesbos, where the Greek commander himself had presumably established a foothold. When Achilles contemptuously dismisses the offer that Odysseus has conveyed (he says that he can find a bride for himself), he may be arguing that his status on Lesbos is superior to Agamemnon’s. The island, then, is thoroughly Homeric, and one which the Chian poet doubtless knew like the back of his hand. Moreover, the Dutch guide tells us, recent archaeological finds at Thermi, not far from Lesvos’ capital, are remarkably similar to finds in the vicinity of Troy.

In a miniature imitation of Homer’s Telemakhiad (the first four books of his Odyssey) and of the greater circuit of Odysseus himself (from Ithaka to Troy and back), author conceives two outings from Mytilini, the first a short trip today on foot to Loutra and back, the second a much longer trip by bus, day after tomorrow, to Kasteli near the top of the Oros Olympos. Without a map in hand he will venture forth from the limitations, dangers and pleasures of the urban scene onto the coast and, later, into the island’s interior.

Early philosophers up to the time of Socrates, who attended the lectures of Archelaus, a pupil of Anaxagoras, treated numbers and motions, and the origin from which everything arises and to which everything returns; they eagerly inquired into the size of the stars, the distances between them, and the heavens. But Socrates was the first who called philosophy down from the sky, placed it in cities, even brought it into people’s homes, thereby forcing them to examine life and conduct, good and bad things (Cicero, The Tusculan Disputations).

“After the death of Alexander the Great, at the end of the third century B.C.,” says another guide, “Lesbos fell under the sway of the Ptolemies. In 88 B.C. the Egyptian hegemony gave way to the Roman. As for cultural history, in the fourth century B.C. the Peripatetic School, given its impetus by Theophrastus, forwarded scientific study, in particular plant biology, but also philosophy, especially in the fields of metaphysics, logic, ethics and rhetoric. Alcaeus was born in Mytilene, Sappho in Erissos. The latter set up a school in Mytilene, where young women were instructed in music, poetry and good manners. Plato called her the tenth muse. Much later Aristotle and Epicurus here continued Theophrastus’ initiative and offered formal philosophical instruction.”

Taking the coastal road out of Mytilini, author arrives within minutes at a hillside park, quite wild and charming, and continues along this route, which offers occasional views of a sea today breathtakingly blue. In a small cove a swimmer challenges its icy waters. As the road degrades into gravelly sand what appears to be a restaurant arises on the cliff to our left. Mounting many high steps, we arrive instead at an Orthodox Greek chapel, decorated with charmingly primitive murals. Foregoing a climb into the adjacent fortress, author returns to the road in the knowledge that eventually he will arrive at the north harbor, for he has studied Lesvos’ geography, even if he has not brought along a map. Before long, after passing a number of handsome but inexplicably deserted houses, he winds down a narrow path into the drabber, commercial harbor at Panagiouda.

Along smaller roads he tends inward, hoping that his sense of direction will eventually return him to Mytilini. So remarkable, then, were the life and death of Socrates that he left behind many followers of his philosophy, who competed in their eagerness to discuss moral questions, wherein the topic is the highest good by which a human being can become blessed. Suddenly he comes upon a great surprise: a taverna in honor of Hermes. So various were the views that the Socratics held about this end that — though it seems hard to believe about followers of one teacher — some, such as Aristippus, said that the highest good is pleasure, and others, such as Antisthenes, that it is virtue (Augustine, The City of God). All is liveliness and hospitality, the clientele entirely native. As he grew older, one of the nymphs of Sicily bore to Hermes a son. At 2:30 in the afternoon the tables are full, the walls too filled with native art: Daphnis, as he was called, fell in love with Lyce, another nymph, who feared that she might lose this lover-god of hers. Sepia photos are gradually blackening and whitening into modern photographs. “Dearest love,” said Daphnis, “I swear before the gods that I would let you blind me with your own hands, if ever I should leave you for the sake of another woman.” Colorful paintings are also in evidence; one shows a man on a hospital bed resuscitated by a transfusion of ouzo, which drains from an upside-down bottle. Henceforth Daphnis fell in love with a princess who offered him the magic herb of forgetfulness. The taverna’s owner seats author at a table alone and serves him a glass of ouzo. When he partook of it, he of course forgot Lyce. He causes him to be served magnanimous portions of native dishes.

Returning to her, his eyes opened wide in terror, and as they did so, pains began to shoot through them. Soon the agony was unbearable, and so instinctively he closed his eyes. When he opened them again, he found that he could no longer see. Like Homer himself, he had been blinded.

On the second day, in search of greater perspective on Mytilini we mount a hill and follow a narrow route in the direction of Kalloni. Aristotle is important in the history of Greek philosophy not only for his own philosophy but also for his view of the history of philosophy. It is Sunday and also the day of Karnivali. A young man conversing with a group of women has painted his face half red, half white. His study and criticism of his predecessors provides important support for his own views. Children are decked out in appropriated versions of Mickey Mouse and other Disney characters. He argues both (i) that his predecessors have gone wrong by neglecting some distinction that he has made clear, and (ii) that his own views are often simply clearer formulations of points that his predecessors had already grasped incompletely and inarticulately (Terrence Irwin, Classical Philosophy).

As we continue to mount higher a squadron of yellow jackets, teenagers dressed in black pants and black shirts with yellow horizontal stripes across their shoulders, midriffs and thighs, swarms by. The Stoics (says Diogenes Laertius) compare philosophy to an animal, likening the logical part to the bones and sinews, the ethical part to the flesh, and the natural part to the soul. Atop their heads waggle antennae in red or gold. Or again they compare it to an egg. If not a festive, there is certainly an expectant, air to the scene. For them the shell is the logical, the albumen the ethical, and the yoke the natural part. Author falls in behind the yellow jackets, as their wings, made of mesh, encircled in black plastic, flutter slightly in the wind. Or, they compare it to a productive field, of which the surrounding wall is the logical, the fruit the ethical, and the land or trees the natural part.

Within a hundred yards he has arrived at a congestion of people in various costumes: clowns with white hair and stovepipe hats, their white silk pants ornamented with black musical notes; another group of entertaining figures, their right pant legs in red, their left in yellow, their hats in yellow and red, their shirts in blue and orange. Or they compare it to a city that is excellently fortified and governed in accord with reason. Kids it seems are assembling in anticipation of a parade and have congregated before descending the hill. Some of them say that no part is separate from another, but rather the parts are all equally mixed together. Another passel of youth is dressed as butchers, red and blue painted stripes running vertically down their faces. Yet another group has donned anachronistic outfits of ruffles in yellow, blue and pink. Several thirteen-year-old girls have adorned themselves as hippies, their cheeks painted with green peace signs and red hearts, their long hair drawn back and colorfully tied in ponytails.

Others put the logical part first, the natural part second, and the ethical part third. At the tables of coffee houses set along the sidewalk sit middle-aged men playing with their worry beads. Zeno (in his treatise On Rational Discourse) along with Chrysippus, Archedemus and Eudromus are of this party. We have now risen high enough to attain to a village ambiance, the outsider ever more strictly excluded from these ritual clans. Diogenes of Ptolemais, though, starts with the ethical part. A group of kids have been costumed as brightly wrapped presents, their bodies metamorphosed into cubes, from which dangle their spindly arms and legs. Apollodorus puts the ethical parts second. It is 4:30. The sun is shining brightly. It is pleasantly warm. Whereas both Panaetius and Posidonius start with the natural part. The parade, it would seem, is about to begin, about to head for the town’s central plaza.

By contrast with such a profusion of color, we arrive before long at a muted grey-and-white building, closed for the day, its sign reading “Gypsum Technique of Phidias.” The prank that the infant Hermes played on Apollo was hardly his last, for this young god simply could not stay out of trouble. In its window are pristine statues of the Nike of Samothrace, of Hermes with the Infant Dionysus. Once he took Poseidon’s trident and hid it; another time he stole Ares’ sword; once he even dared to abscond with his father’s scepter. Imitations of classical Greek models are interspersed with imitations of eighteenth-century concoctions: If Zeus hadn’t found it almost immediately, who knows on whom he would have vented his anger. Of Aphrodite bathing, or sculptural representations of details from Renaissance paintings, such as Botticelli’s “Venus on the Half-Shell.” Whatever good will Aphrodite may have shown toward those that honored her, she was relentlessly severe with those who did not respect her and dared to scorn her powers. Interspersed amongst these are representations of Christ at The Last Supper, a bas-relief of Leonardo’s famous mural. The handsome Narcissus suffered harsh punishment for treating her in this way. Mary, bland, with an even blander infant Jesus. Among gods and men alike, he was the only one in whose heart the arrows of Aphrodite’s son could not find their mark and make it throb with love. Except for a gold wand entwined by serpents and with wings atop it, held by Hermes, there is not a trace of color anywhere to be seen.

We continue to mount higher but now at a reduced rate of ascent. We seem to have reached the suburban outskirts of the hillside city of Mytilini. “Interamerican,” reads a sign lettered in red on white. A young Greek man in Levi jacket and black pants heads downhill toward town, Walkman receivers in both ears. We pass a farmer’s lonely cottage. Suddenly we have exited from the civilized world.

Socrates: A hill rises on our right. Suppose that someone knows the way to Larissa. Its craggy outer layer cut away to reveal rouge and red substrata. Or anywhere else that you like. On its slopes a flock of scraggly sheep graze on scrubby vegetation hardily surviving among its beige, brown and volcanic black outcrop. When he goes there, and guides others, will he not guide well and correctly?

Meno: Of course. A road sign indicates that we are heading in the direction of the Petrified Forest.

Socrates: Now what if someone has a correct belief about which is the road, without having been there and without knowing it from experience? Some consider the forest to be 1000 years old. Will he not also guide others correctly?

Meno: Yes, he will. But others, who have studied the matter empirically, believe it to 20,000,000 years old.

Socrates: And presumably as long as he has a correct belief on the points that the other knows, he will be just as good a guide, will he not, thinking true things, but without wisdom.

Meno: Just as good.

Socrates: Then true belief is as good a guide to correctness in action as wisdom.

(Plato, the Meno)

Socrates: The scene, as it has become more and more rural. What again are we to say about acquiring wisdom? Has taken on the characteristic odor of the Greek landscape, one that mingles sage and sheep dung. If the body is admitted as a partner in the inquiry, is it a hindrance or not? At a turning of the road we come upon the lengthy text of an anti-American graffito, followed by the red sickle-and-hammer, applied to a white base. For instance, have sight and hearing any truth for human beings? The timeless cliff looming to the right of us belies the sign’s factitious intensity. Or is what the poets are always telling us right, that we neither hear nor see anything accurately? As we have left the town behind and entered these more provincial precincts, the olive tree has evolved from individual saplings into groupings of mature trees into full-fledged ancient groves. But if these bodily senses are neither accurate nor clear, the other senses hardly will be, since they are inferior to them. Or don’t you think so? Amongst them almonds are bursting into bloom.

Simmias: I do think so. Author crosses the road to gain a closer view of the next political graffito, as it unfolds around the bend.

Socrates: Then when does the soul reach truth? It seems to assert that President Clinton, in his Greek foreign policy, is “a liar.” For if it undertakes to examine anything in company with the body, clearly it is deceived by the body. Around yet another bend the mountainside has been slashed away dramatically.

Simmias: True. Three goats consider which direction they should head in.

Socrates: And I suppose that the soul reasons best when none of these things, namely sight, hearing, pain or pleasure, distresses it. The ascent has become considerably steeper. But in as far as possible when by itself it lets the body go and as far as possible has no dealings or contact with it, but aims merely at being. We look down from the inadequate modern road into a much earlier road, smaller again by two-thirds.

Simmias: Certainly.

(Plato, the Phaedo)

Heracleitus says that for those who are awake the world is one and common (Plutarch, On Superstition). We have reached a grouping of modern buildings, one labeled “Alou Systems.” But that when anyone goes to sleep, he enters a private world. The company seems to fabricate aluminum houses and other structures. For the superstitious person, however, there is no common world. Another building is labeled “Kasouras.” For he neither uses his intelligence when he is awake. A third, part of the second, “Strip Club Zephiros.” Nor frees himself from his agitation when he goes to sleep. Behind it rise huge cliffs, cut away by nature: But rather his reason is dreaming. Rust, beige, darker brown and white. And his fear is awake. In a huge declivity filled with wrecked cars and abandoned trucks. He finds neither escape nor relief. Three men are at work repairing a backhoe.

Author braves the parking lot to arrive at another imposing cliff, hacked away by nature. To one side of it, on a milder rise, black and white goats stand at various intervals in amongst sage bushes. Higher up, beneath an olive tree, two of them gaze down on author, who now crosses the road to examine the local options more carefully. The Strip Club, however, proves to be impenetrable: locked doors, mirrored surfaces, a blank exterior.

Beside the thoroughfare a shrine has been erected in memory, it seems, of two children. The nature of the crocodile is this (Herodotus). Within its glassed space sits an icon of Mary and Christ. During the four winter months it eats nothing. A ceramic rose. It has four feet and lives both on land and in the water. A jar one-third filled with honey. For it lays eggs and hatches them out on the riverbank and spends most of the day on dry land. And a cigarette lighter. But it spends the whole night in the river, since the water is warmer than the air and the dew. Outside the enclosed space. Of all the mortal creatures we know, this one grows from the smallest beginnings to the greatest length. On a little ledge. For its eggs are not much bigger than those of the goose. Sit two clumps of cloth flowers. And the young crocodile is in proportion to its egg. Arranged with real sprigs of greenery. But when it grows, it reaches twenty-eight feet and more.

From this point author decides to take a different road, one that heads on up the mountainside. Slowly he pursues his way, clambering over marble outcrop within the roadbed itself. The treacherous footing has been made somewhat safer by a downpour of cement that looks as though a river of milk had solidified. In a culvert below road machinery has been abandoned, along with a tour bus. Likewise, a concrete industrial structure, still in place but ravaged, presumably part of a former stone quarry.

At the summit of the hill ahead stands a man accompanied by his dog. We continue on up this unpaved way past shelves of shale, olive green and beige, which project out toward us from the cliff face. As we emerge at the crest of a ridge the baby blue Aegean opens out to offer a view of the Turkish coastline, where its waters have turned an increasingly whitish, lighter blue.

We have arrived at what appears to be a prison, the house standing before it perhaps that of the jail keeper. By now we have traveled at least a couple of kilometers from town, most of it in steep ascent. Below us the rooftops of Mytilini are at last visible. The wind, as it blows in our direction, wafts with it the intermittent sounds of carnivalesque activity.

This hillside has certainly been cut away by man. Blocks of rock as yet unfinished have been piled alongside the roadway, rust-red dirt still clinging to them. We pass a large sentry’s stand, once occupied perhaps by the quarry’s foreman. Scattered amidst the landscape: a tank for gasoline, an abandoned truck tire, a rusty piece of machinery, a conveyor belt.

Improbably, as we have traversed this desolate route, a fair number of cars have been passing us, all driven by single men in their late twenties, or early thirties. The road has swerved to the left and now rises to another crest of the mountain, which offers a view to the north of the waters of the Aegean as they extend toward Thrace.

We approach the city dump. Bordering our route are loads of construction detritus, randomly deposited. At a fork in the road author waits to see which way the next car will turn. A military personnel carrier appears and turns to the left. Prudently author turns to the right. Within a few hundred yards we are offered a view down into the city’s power plant, its smoke stacks striped alternately red and white. Below in the valley, scattered across a sun-raked slope, several dozen sheep are grazing, all either black or white.

Our general view of the sea has become more comprehensive, interrupted only by a knoll topped with pine, chestnut and plane trees. Across this vast panoply, against the Aegean’s mild blue, but a single freighter, its hull black, its superstructure white, can be discerned. After an interval of five minutes the military vehicle that had passed us reemerges on a brand new black asphalt ribbon far below. Ahead, on our narrow path, appears a cemetery, beyond which the tip of the fortress seen on yesterday’s outing.

It would seem that we have reached, if not strictly speaking the city limits, at least its confines, for we begin a descent along “Odos Ag. Kiriakos” (St. Kiriakos Road), arriving finally at the grounds of the cemetery, within which is set a large Greek Orthodox church. The plot is crammed with unornamented, modern sarcophagi, for the most part raised above the ground. On many tombs flowers have been arranged, or merely left behind. Having averted the gaze of two mourners, author decorously exits by the cemetery’s side gate, so as to begin a more direct descent into the city’s streets.

The most precipitous downward motion begins at the very edge of town. Cautiously we negotiate another road, turn right past a flowering apple tree, and begin an even steeper descent into a narrow alleyway. Here the houses, some stuccoed, are modern, none more than thirty or forty years old, all impeccably neat and clean. In red-and-black ruffled costume, wearing red lipstick, her pigtails wrapped in black gauze, a little girl steps out into the street to regard the passing phenomenon. On the marble porch of her well-appointed house sit two motorcycles. Across the street stands a pork butcher’s shop, the heads of several swine hung outside by their snouts. We have entered Odos Diafanos and arrive at a lemon tree, its fruit nearly ripe. Beyond it, before an olive, beige and white-pilastered house front, a cherry tree is blossoming.

Socrates: The lovers of sounds and sights, I said, delight in beautiful tones, colors and shapes, and in everything manufactured out of these, but their thought is incapable of taking delight in the nature of the beautiful itself.

Glaucon: Yes, that is so. Having descended another two or three blocks, we pause at a café to imbibe a cup of the sweetened, semi-liquid Greek coffee.

Socrates: And on the other hand, few there are who are able to approach the beautiful itself and see it in itself. The proprietress seats us before a tinted photo of three men in a gondola serenading two blond girls in full evening dress, who in turn are seated on a Venetian terrace.

Glaucon: Few indeed.

Socrates: And so if someone recognizes beautiful things, but neither recognizes beauty itself nor is able to follow when someone tries to guide him to the knowledge of it, his life is but a dream. For is not dreaming, whether asleep or awake just this: thinking that what is similar to something else is not merely similar, but is the very thing it is similar to?

(Plato, The Republic)

Having finished his coffee, author decides to reverse his course and head upward again in search of the ancient theater. As we remount Odos Ag. Kiriakia, we pass a great prickly patch of cactus. Behind staggered ramparts we glimpse another Greek Orthodox church, this one newly building. Through roadside cypresses it rises above us. To the other side of the road, again through cypresses, we look out over the water. Leaving this rather large and handsome church behind, we continue our steep ascent, re-encountering the smaller, older church whose grounds had housed the cemetery. This time we turn down another road to reach the theater’s precinct. Once again the road mounts higher, once again the Aegean opens out before us, now muted and greyed by corduroy cloud cover recently formed.

The gravelly path continues to rise, higher and higher. For the ancient Greeks, at least for Lesbos’ inhabitants, the theatrical experience was preceded by a bout of considerable athleticism. Doubtless this contributed to the eventual catharsis. When we arrive at the gate to the theater, however, we find it barred. The third man is proved in the following way:

For his final descent author chooses a path down a needle-strewn slope. We cut behind the new church onto a graveled way, in the hope that it will lead back into town. For suppose that what is predicated truly of some plurality of things is also something other than and apart from the things of which it is predicated, being separate from them. Beside the road an orange Volkswagen bus has been overturned, pushed farther off the road, then riddled with bullets. This is why, according to them, there is such a thing as man-itself. Ground cover along this peripatetic way is uniformly green. Because the man is predicated truly of the particular men. Here, sounds of the city’s Carnival activity easily reach the ear. These consisting of an evident plurality. We sway back and forth along a path that devolves into double tire ruts. And therefore other than the particular men. Fleetingly, from time to time, we glimpse the buildings of the city below, the outline of its harbor. Now, if this is so, there will be a third man, for if the man being predicated is other than the things of which it is predicated and subsists on its own, then the man is predicated both of the Idea and of the particular. At last we exit from this philosophically calm precinct into an avenue, where we come upon the town’s aquarium. In the same way, there will also be a fourth man predicated on this third man, of the particulars and of the Idea, and similarly also a fifth, and so on to infinity (Alexander, Commentary on The Metaphysics).

We are still quite high above the city proper. Beneath us, in the courtyard of a public school, kids are playing soccer on a green asphalt apron. As we continue, a broad sidewalk materializes, its steps, in lieu of a street, leading us in a more regular way down the hillside. The established houses bordering it are a century old, attractive, if somewhat conservatively painted in grey, beige and blue. No sign of life is visible behind their carefully curtained and shuttered windows. As author speaks these words three boisterous sixteen-year-old girls, gaudily attired in knee-slit jeans and bandanas, confront him, wielding baseball bats. Mockingly they shout at him, then, with a laughing compliment, head on up the street.

We have reached a new level of antiquity, follow an only slightly sloping course and enter into Odos Theocritou. Through a grate on her window an older woman in a blue dress looks down quizzically at author. By twists and turns we arrive at the town’s cathedral, atop whose spire is affixed a three-dimensional cross, a cross, that is, with four arms. In its courtyard bronze busts of patriarchs sit atop marble pedestals. Within the church the sound of a cantor is audible. A service in progress, author declines to enter the sanctuary. We conclude in the market street, where on this holiday only a fishwife, a florist and a baker are open for business.

As we turn and head back toward the Hotel Sappho, in the alleyway we encounter a red-faced, red-tailed girl in a black overcoat. Above her head she raises a red trident.

We are departing from Mytilini on a “long distance” bus destined for Kasteli. “Since you are a friend,” said Telemachos to Mentes (Athene in disguise), “I will tell you all our woes.” We are leaving behind the music club called “Kirke,” the grey destroyer P-99 moored in the harbor, its sailors lounging on deck. “This would be a happy house, if only my father could be here.” We are winding our way out of town on a route that leads to the airport. “Yet he is lost because the gods were envious of his exploits.” At a fork in the road we diverge to take a more inland course. “Even if I knew that he had fallen at Troy, among his comrades, it would be some consolation.” We pass a liquor store called “New Wave.” “For then at least a monument could be raised to him and I could revere his memory.” Another right turn sends us yet farther inland, past a large institutional building whose name goes by too quickly for recognition.

Our route is taking us along a road behind the road that had earlier taken author past the strip tease club. “But he has disappeared ingloriously and left me with a host of bitter troubles.” We head directly for a cleft in the mountain. “For it is not only the loss of my father that I lament but all these fortune hunters whom you see flocking to our house.” The way begins to narrow and wind through an olive grove. “They are the sons of the noblemen of Zakynthos, Kephallenia, Doulichion and Ithaka, all competing for my mother’s hand in marriage.” Momentarily we descend to a view of the sea. “They abuse our hospitality and eat us out of house and home.” But within a few minutes we have reached the crest of this mountain, from which we peer out over a large bay, the Kolpos Geras. “They will not budge from here until my mother chooses one of them.” By hairpin turns we begin our descent, but as we descend the turnings become ever more gentle. “Our fortune is draining away before our eyes.” The day is blond and serene. “And on top of that they threatened my life.” As we approach each curve the driver honks to warn off on-coming but as yet invisible vehicles.

It has been an hour’s journey, through Kerameia, Ippeio, Asomatos, but finally we arrive at our destination, a friendly little town situated near the intersection of three roads. Author is the last to get off the bus. In the small triangular town plaza stand a vegetable and fruit market; a trophy store; and two outlets, side by side, for cigarettes and candy. Across the way, in the post office courtyard, an orange tree displays its ripening fruit. At the next house down a eucalyptus spreads its branches out over the street.

Traffic through the square is rather brisk on this holiday, the second day of Karnivali. A boy in a purple work shirt trots upward on a grey nag. An old woman, in brown sweater and blue babushka, strolls back down the hill toward us. Most people, though, are driving through the plaza in their own cars: Opel Astra, Nissan van, Renault coupe, Volkswagen pickup. As author has stood observing these passersby, a dozen cats have also traversed the square, each careful of his or her territorial prerogatives.

Now a taxicab arrives from Mytilini to deposit four of its five occupants, which include two children. Perhaps on this holiday a family in the mountains has been visiting its relatives in the harbor. At any rate, all are still in a festive mood. Two twenty-year-olds arrive on a motorbike to mount the hill quickly, the first in yellow windbreaker, the second in red and blue. Author takes seat across street at a small café, where a white tablecloth has been spread, ornamented with two blue butterflies. Closer inspection reveals that the “cloth” is made of paper. He changes seats for an uphill view of the town. Rising slightly above this restaurant’s porch is the terrace of an ice cream parlor. On a tree painted pale green to a level of three feet a sign has been attached that depicts a vanilla ice cream cone with an ampersand above it.

“Flushed with indignation, Athena answered sharply:” Not everything that appears is true. “‘Telemachos, you are no longer a child but a full-grown man.’” First, even if perception, at least of its proper objects, is not false, still, appearance is not the same as perception. “‘If only Odysseus, with his matchless cunning and bold strength, would arrive unannounced to stand here in the doorway with shield and helmet, bearing two spears, just as I once remembered him!’” Furthermore, perception itself raises many puzzling questions, such as these: “‘Let me, however, first ask you.’” “Are magnitudes and colors such as they appear to observers from a distance or such as they appear to observers close at hand?” “‘Why don’t you call the people of the island to a meeting and tell them what you are suffering at these suitors’ hands.’” “Are they such as they appear to healthy people or such as they appear to sick people?” “‘Then order these drones to pack their bags and go back to where they came from.’” “Are things heavier if they appear so to feeble people or if they appear so to vigorous people?” “‘Call on the gods as witnesses that if they do not leave the palace they will come to a sorry end.’” “Are things true if they appear so to people asleep or if they appear to people awake?” “‘And another thing:’” It is evident that they do not really think the appearances of the dreamer are true. “‘If you know what’s good for you, take the trouble to find out whether your father is alive or dead.’”

Author’s bread and salad arrive, along with a glass into which a folded napkin has been inserted. On the table sits a saltcellar, one-third full. Beneath the ice cream cone on the shop’s sign read in Greek letters the words “Gluka” and “Utopia.” When the salad arrives, it consists of a mixture of greens, heavily seasoned with oil, vinegar and salt; two slices of carrot, two peppers, and a pickle; plus several delicious small black olives. Before long three small fish make their appearance, hot from the grill, one full of roe.

“Athena continues: ‘Take twenty good oarsmen and your fastest ship and set off for Pylos to find old Nestor.’” Certainly no one who is in Libya and one night supposes in a dream that he is in Athens sets off for the Odeion. “‘If he knows nothing, at least he will give you good advice.’” (Aristotle, The Metaphysics.) “‘Next make your way to Menelaos, in Sparta, for he was the last man to return from Troy; surely he will have some news for you.’” Furthermore, as for the future, Plato says: “‘If you hear that your father is alive, be patient and await him, for he will return.’” “The belief of a doctor and an ignorant person surely do not have equal authority.” “‘But if you learn that he is dead, then raise his tomb-mound high and offer funeral sacrifices; when that is done, make sure that you get rid of these hangers-on.’” For instance, about whether someone is or is not going to be healthy. “‘You’re a grown man now, Telemachos, and either by stealth or direct action you must find a means to do away with them all.’”

Across the way a man on a white-and-blue Honda motorbike stops, enters the fruit and grocery store and exits bearing two bottles of Fanta and one of ouzo. As he remounts his bike, the back of his sweatshirt reads “Heroic Giants / Dodgers.” Paying his bill, author leaves the café and begins his climb up the red-and-grey cobblestone street, past a second café, then quickly past a third. “New Democracy,” announces a poster, a picture of the party’s candidate in the storefront. Within a few more yards another political party advertises its candidate.

We have reached a second plaza, this one more complex, made irregular by the terrain. “2000,” says its planned graffito, “ A Good Time,” underneath it a five-pointed star. In this square all the shops are closed for the holiday, which makes investigation through their windows easier. At the barber’s, author observes, the customer sits in a chair before an ornate dresser of nineteenth-century vintage. Within this tiny emporium there can be no question of entertaining two customers at once. From a second story’s narrow window a comely woman looks down upon author, half concealing herself behind its curtain.

“Having spoken these words the goddess transformed herself into an eagle and soared into the heavens.” The ascent continues, more arduously. “Telemachos stared up at her in wonder.” Finally we arrive at the level of the clock on the Greek Orthodox church. “He knew now that it was not a king called Mentes who had spoken with him, but rather Athena herself, and this filled him with new strength and courage. He would follow to the letter the advice that the goddess had given him.” As we rise above the ancient tiled roofs, the roadway narrows to the width of a footpath, paved in cement.

“Phemios was still singing and they were all listening in silence.” We look down into a forested gully, out over the flat rooftops of the town, past a valley on toward the mountain, seen almost entire as it rises above the inlet sea. “His song told of the Achaeans’ return from Troy.” We find ourselves in the “Road of the 18th of November,” so narrow, at its turning, that we can almost touch the buildings on both sides of it at once. “Hearing this song from her chamber, Penelope came down the stairs, accompanied by two serving girls, her eyes filled with tears.”

“Phemios,” she said, “since you know many other actions of mortals

and gods, sing for the suitors one of those, and let them in silence

go on drinking their wine, but please leave off singing this sad

song, since an unforgettable sorrow comes over me, beyond all others,

so dear a head do I long for whenever you remind me of my husband.”

A young man drives by on his yellow Suzuki bike, exercising it as though it were an animal. “In answer the thoughtful Telemachos asked her:

“Why, my mother, do you begrudge this excellent singer

his pleasing himself as the thought drives him? It is not the poets

who are to blame, it is Zeus who is to blame. And there is

nothing wrong in his singing the sad return of the Danaans.

So let your heart and let your spirit be hardened to listen.”

We have reached the mountainside outskirts of the town and begin to rise higher still. In the breeze the leaves of a grove of olive trees turn their silvery sides toward author. Their trunks are wizened and complex. On his yellow steed the boy returns. “When this peerless woman had left them, the suitors became noisy. ‘Stop!’ roared Telemachos through the hubbub of their conversation. ‘I will have you here no longer. Tomorrow I will call my people to a meeting and tell them what has been going on within these walls!’”

At last we have reached a height at which only a donkey observes us, though we have by no means climbed as high as the mountaintop. Here the road begins its descent. Before a substantial house have been parked two red vehicles, one of recent vintage. A little farther along and we pass two motorbikes, in identical red, one a “Virago,” the other a Honda “Melody.” The sidewalk itself is red, paved in rust colored tiles but with yellow ones interspersed. As we return into the town’s original square we notice a second grocery store, a new house, the latter still under construction. This wall of the ice cream parlor, like the tree that stands before it, has also been painted pistachio.

Author takes a seat opposite one of the two cigarette-candy stores to rest for a moment. With no bus available for his return to Mytilini today, he must soon begin his descent of the mountainside, the first stage in the long walk ahead of him.

↔