Chapter 12: The Killing of J.F.K.

Drinks served, the flight attendants took their seats again. Kathy gazed down onto the scene below: an ocean liner en route to the New World; in the middle distance, extended banks of cumulus. Four hours had drizzled by since takeoff. Kathy tilted her seat back, tucked a pillow behind her head, and opened a book she’d picked up at the airport.

“It was dark, horribly dark. The lights were shut off all over the park. At 11:00 o’clock the police began to mass opposite the barricade. No one really thought that picnic tables and wastebaskets would stop an invasion of cops, but after what had happened earlier today and Sunday it was sort of reassuring to have something between you and them. A kid in the National Mobilization Committee began to rub Vaseline on his face. He handed me the jar, urging me to do the same, I optimistically declined. A girl wearing a McCarthy button nudged me to ask me for a light. Nervously she said, ‘Should anything happen, stay by me.’ People who had climbed atop the barricade shouted things like ‘Kill the pigs!’ and ‘Hell no, we won’t go!’ The remainder of our contingent, a thousand of us, chanted or milled about. Someone next to me pointed over my shoulder saying, ‘Oh wow, look who dropped in!’ I turned and saw four men in the light of a small trash fire moving toward me with locked arms. Among them were Allen Ginsberg and a small guy in a suede jacket. ‘Beautiful, that’s Jean Genêt,’ said a kid in a University of California tee shirt. The only time I’d ever seen Genêt was on a book jacket. So it seemed strange to have him walking toward me. They stopped fifteen feet from the barricade. Ginsberg sat in the grass and started an OM chant. Others joined in until this side of the barricade resounded in one harmonious voice. A few shouts from the other side excited twenty or thirty people into running. The demonstration marshals yelled out ‘Walk!’ During the next scare we were told to sit down, that no harm could come to us. The first and second alarms caused my stomach to knot up. Before the onslaught I stood there thinking about our sins: about the body of Robert Kennedy, stretched out bleeding before cameras and reporters; about the pictures of Martin Luther King, Jr., on a balcony, men surrounding him, pointing at the invisible assassin; about the war; about politics; about cities burning. Suddenly screaming broke out all along the barricade. Canisters of tear gas exploded. The McCarthy girl tugged on my arm, yelling at me to ‘Come on.’ We ran in the direction of the pond. I could hear the police crashing through the line of tables and trash cans. They were armed with rifles and were screaming, ‘Kill those fuckers! Push them in the pond!’ A cop grabbed my jacket. I fell, and a couple of them started kicking me. ‘We’re leaving! OK, we’re leaving,’ I pleaded, but they wouldn’t stop. Finally one of them picked me up and hurled me into the pond. The girl had been thrown to the ground. She was surrounded by cops, pelting her with clubs. Somehow I managed to pull her away and drag her into the water. She was badly beaten about the head.”

Kathy put the book on the plastic fold-out table in front of her. Pulling a pad of stationery out of her handbag, she started a letter:

July 28, 1976

Dear Elizabeth,

At the moment I’m over the Atlantic. Planes are enchanting and to fly is to be in a fairy tale. In two hours we will land in Dublin, where Mother will be waiting for me with roses. It’s kind of a tradition with us.

I suspect I’ll find two letters waiting for me, one of them from you, telling me about your adventures with Hidio at Disneyland; the other from Santa Fe. I’m really sorry Linda and I couldn’t be friends.

I’ll write you a long letter soon. WRITE ME, and take care.

Love,

Kathy

Kathy spent several days in Dublin with her mother. Together they visited Trinity College, whose library Kathy found especially impressive. “During the Dark Ages,” her mother told her, “Trinity College was a great center of learning.” Another day Kathy returned to the college to hear a public lecture titled “Recent Developments in Cosmology.” “Is the Steady State Theory on its way out?” asked Hermann Bondi. This wasn’t really Kathy’s cup of tea. She shifted restlessly in her seat. As she looked at the clock on the wall, which had stopped moving, she felt a warm hand take hers. It belonged to Michael O’Faolain, her date for this evening. She decided to hear out the bushy-haired instructor from Cambridge.

“The fact that the galaxies are racing through space at a fantastic velocity has provided us with a fascinating riddle.” Kathy looked at Michael and tried to recall everything she knew about the origins of the universe. “Which, then, is correct?” asked Bondi rhetorically, “the Big Bang, the Steady State, or the Pulsating Universe?” Michael gave her a kiss on the cheek. “There are periods when all the galaxies fly outward. These are succeeded by periods of recession.” The clock had started to move again. “The mass of the universe collapsed upon itself.” “Let’s go to a pub,” Michael proposed. “The collapse is then followed by an explosion in which new galaxies are formed.” Kathy nodded. “This goes on ad infinitum.”

The lecture finally over, Kathy and Michael settled into a booth for some Irish beer. Irish beer takes some getting used to if you’ve grown up on American beer. Before she knew it, Kathy was drunk. Fluid thoughts swam in her head. “You must be Dylan Thomas,” she barked, directing the accusation at a curly-haired man at the bar. Rather than contradict the misguided Yank, the man recited a snatch of “Under Milkwood.”

Kathy fell into bed with her clothes on, gripping the sides of her mattress to hold the universe together. As her stomach turned flips, the bedroom whipped itself into a vortex.

She caught glimpses of stars expanding into galaxies. Her stomach was tied in a knot. As she fell asleep a tiny voice from somewhere in the room was singing:

At Bailey she drank

More than her love’s share.

The battleships sank,

Her head light as air.

For she outdrank

(Oh she outdrank)

Wellington’s whole army.

Next morning Kathy awoke without memory of the song or the bar. It was Sunday, August 1. Around 3:30 that afternoon, she found herself in Phoenix Park. There among the violets she came across an elderly man in a floppy hat who was pulling weeds. As Kathy approached, he looked up, adjusting the wire-rim glasses which had slipped down his nose.

“Well, well, look who’s come,” he said. “It’s Katie from the Historical Society. Aye, young lady, you can turn right around, for you’ll be getting nothing more from me.” There apparently was some misunderstanding. Kathy tried to explain who in fact she was, but the gardener seemed to be deaf. “I suppose you want to hear more tales of the Easter Risin’,” he said, ignoring Kathy’s puzzlement. “Well, good day to you, miss.” Kathy turned to leave. “Now wait a minute,” said the old man, “don’t you be going off like that, snifflin’ and carryin’ on so.” Kathy shook her head in disbelief. “I’m no encyclopedia,” he complained, “and I’ll not be treated like one.” The old man took a deep breath, looked at Kathy again, and blinked. Kathy decided to stick around after all and see what he had to say.

“The victory,” he began, “didn’t matter at all. It was the battle, the battle. Better to fight than submit. Ah, the poetry of conflict.” Kathy brushed a strand of hair behind her ear. “Oh, I don’t claim to know much first hand, bein’ but a lad o’ nine at the time. But I do remember some things.” He wiped away a dribble of spit that had formed at the corner of his mouth. “Well, there they were, Sunday mornin’,” he continued, “marchin’ down O’Connell Street, headin’ toward the center o’ town. ‘Where ye off to?’ says I to one o’ the lads. ‘Don’t know,’ says he. They was headin’ toward the Post Office, you see.” Kathy smiled. “There was three brave fellows leadin’ the parade that day, wearin’ green uniforms, with great sabers and Sam Browne belts. And two of ’em were poets!” the old man exclaimed. “I had no notion they were poets at the time, poets lookin’ as they do like reg’lar people. And there was James Connolly too, with his large moustache, standin’ between the poets. And on his left, Joseph Mary Plunkett, lookin’ sickly and thin, but marchin’ anyway. He had a big bandage wrapped around his neck. And to his right, Padraic Pearse, handsome figger of a man. And I run up alongside Pearse and says, ‘Where would ye be goin’, sir?’ Pearse looks down at me. ‘There’s work to be done here lad. Be off.’ Aye, that’s what he said.” Kathy smiled again. “So I ran home, and me mother wouldn’t allow me out of the house for the next seven days.” Kathy nodded in sympathy. “When I heard those men were dead, I swore I’d never forget what they looked like.” Again Kathy nodded, but the old man had turned away and was kneeling in the flower bed. “Now, young lady, I’ve a lot of work to be doin’ here. Maybe another time.”

Kathy and her mother took up residence in an old hotel overlooking the Louvre from the quai Voltaire. It was August 4. Their room was comfortable but not especially quiet. You know, reading about places that you’ve never seen is a different enterprise than being in those places. The odor of the Seine in summer, and its description, are two distinct things. As for the tourist, the touch of jagged stone may prove as irreplaceable as a view of the Eiffel Tower. Suppose, for example, a friend describes your favorite meal, or even sends a photograph of the dishes. If you are starving, is that compensation?

Thus far Kathy’s exploration of Paris has taken her no further than the hotel bar. A downpour, drenching the city, has prevented her from venturing out. Her appetite for scenery, in short, had not yet been satisfied. In the hotel room she leafs through the pages of French magazines. Her mother suggests a game of cards. They play on into the night, hand after hand, till Kathy is smitten by a dreadful thought. What if she were forced to play gin with her mother forever? The horror, you see, is mathematical, for somewhere, in infinity, the mother and daughter would have to repeat each hand they had ever played, each word they had spoken to one another, every error made. Every repetition, in turn, would be repeated to infinity. Once more Kathy thinks of Professor Bondi. According to the physicist, her fantasy may be a universal fact. In that case, Kathy reflects, only an infinite lapse of memory can make life bearable. Better to forget all this.

The rain continues, washing the bricks of Notre Dame, falling off the darkened, conical towers of the Hôtel de Sens, onto the roofs of taxis, onto the paving stones of Paris. As the city undergoes its cleansing, Kathy soaks herself in a warm bath.

Now everyone who can sleep in Paris is asleep. It is early morning. The rain has stopped. On the right bank a policeman walks alone down the rue de Rivoli. Reaching the Ministère des Finances, he pauses to light a cigarette. Another man steps from the shadows to greet him, but the agent is deaf to his voice. The stranger approaches. The policeman fails to perceive him. For you see, ontologically speaking, the man is without substance. He exists only in fiction, cannot be apprehended (at least not in any normal sense of the word). It is only because you and I are not there that we, through an artifice, are granted omniscience. And what of the policeman? – but let that pass. For the man of the shadows has stepped into the light. Let us listen as he speaks, observe his demeanor, his manner of dress. “Each of us,” he begins, adjusting an eighteenth-century hat, “each of us puts in common himself and his entire power under the supreme direction of the general will.” The voice is resonant and, as the man turns left into the place de la Concorde, it fills the vastness of Paris. “In return, each of us receives, every member, an indivisible part of the whole.” The man has taken off his hat and is now gesturing broadly toward the Assemblée Nationale. “Under bad governments equality is only apparent and illusory; it serves only to keep the poor in their misery, the rich in their usurpations.” Having reached the pont de la Concorde, he gazes toward the Île de la Cité. “Laws are always useful to those who possess and harmful to those who have nothing; therefore it follows” – he loosens the bow of his oversize tie – “that society is advantageous to people only if everyone has something and none has too much.” With this he flings his neck wear into the river below, striding onward toward the rive gauche. His identity is evident, yet no one in Paris hears the voice, no single soul hears the football of . . . Jean- Jacques Rousseau. Not even the people of Paris still awake!

When Kathy awoke, it was not to the sound of voices but to the clatter of a laundry truck, chugging down the rue des Saints Pères. The sound was normal for Paris, but it struck Kathy as uncommon. After a breakfast of petits fours, she and her mother set out for a sightseeing tour of the monuments, lunch in a fine restaurant, visits to several museums. Mid-afternoon, they stopped at a café. Inside, by the window, sat a man with a leather notebook. Kathy observed him. Most of the time he stared out into space, but some of the time he wrote quickly. Words gushed out of his pencil like hot butter. Kathy noticed he spent a lot of time on his pencils. She also noticed he was the only person there drinking rum. Before long, the writer noticed Kathy too. He liked her. He liked her long reddish hair. Probably American, he thought. He looked at his book, and then he looked back at Kathy. That one’s mine, he said to himself, mine if I want her. He put her down on paper. Nervously, Kathy glanced at the famous writer, who kept on writing. His table was littered with pencil shavings, the glass of rum half empty. What did it matter to him? She could stay for a minute. She could stay all day. What did he care? He had her down on paper.

1670. “What should be done with the soldiers whose wounds have won glory for France?” Kathy had spent the evening at the hotel reading guidebooks. “What can be done for the soldiers who have grown old?” She thought she might like to spend a whole day at the Invalides. “Have they been forgotten? Deserted? Did they desert France in war?” Napoleon fascinated Kathy, she didn’t know why exactly. “Should the soldiers be put to work sweeping out churches or ringing bells?” And Louis XIV too. “What kind of work is this for those who spilled blood for France?” She had picked up a thin green book and was looking at the figure on the cover. “A place shall be built for them.” She looked at her mother, but her mother was asleep. “These men are the King’s, and they will be welcomed to his household,” the voice went on. “Welcome, O brave men. Welcome, O sons of France.” Dreamily Kathy thought of Victor Hugo. “Welcome to the Invalides.” She’d fallen asleep, the green book unopened in her lap.

“Welcome honored soldiers, your kings think highly of you whenever you go into battle, whenever you kill and are killed for France.” The words continue to ring, but it is July 1839. A cabinetmaker, one of Victor Hugo’s neighbors, pays him a visit. He has come for advice on a matter of utmost importance. The great poet declares himself an amateur in the connoisseurship of furniture, but nonetheless agrees to accompany the man to his little shop in the rue des Tourelles. As he enters the room, Hugo finds it crowded with a huge ebony box, eight feet long, three feet wide. It is the coffin destined for the emperor himself. Standing before it in the silence, Hugo contemplates its quiet dimensions. When the lid, he thinks, is closed upon this coffin, no human eye shall ever look in it again. The poet takes great care to offer what advice he can. Chiefly he recommends a change in the materials of the lettering. “An Egyptian tomb, a Greek sarcophagus,” he explains, “should be blazoned not with copper but with gold.”

Dear Elizabeth,

Paris is like a fossil and I feel like an archaeologist. To live here must be like living in an enormous ruin or museum. If you ever come to Paris here’s some advice: (1) before you pick a hotel, decide what district you want to live in, (2) buy a pocket dictionary. And (3) read a travel guide before you get there.

Today I walked over to the Invalides and visited the whole thing – where Napoleon is buried, as well as a church, the other church, where they have all his junk. On the way out I was stopped by a Swedish sailor who spoke to me in French. All the time he talked he stared at my chest. You would of thought this guy had been at sea for years and years.

You remember my friend Mary? Well, she’s moved from New York to Chicago and will be going to the Art Institute there in the fall.

Donald says he’ll meet me at O’Hare. I’m looking forward to that. And Oh, I may not be back in time to pay my half of the rent. Could you pay it? Of course I’ll pay you back, when I get to Santa Fe.

Much love,

Kathy

By now it was evident what Donald had to do: he could stay in his life or step outside and get the picture. He opened the door of his Mustang, leaving Mi Tu asleep on the back seat. He sat down under a tree and thought about Linda’s parting words: “After the divorce things’ll be different.” He was beginning to see it all. His life had been a succession of facades. And who was he fooling? He was fooling himself. He had wanted to be a great American writer; and he was good, damn good. But he wasn’t good enough. Who was he kidding? He’d been lying to himself. At first they’d been harmless lies, but soon the whole thing had got out of hand. Now he was caught, caught in the teeth of his own neurosis, lured like Faust to the depths of Hell. The dream world, this underworld he now inhabited, must be broken out of. “You have to wake up!” He was muttering to himself. “You must rise from the vault and shatter the fantasy. Identify the victim’s body and perform the post mortem.” I’ll survive the separation, he said to himself. And then, like a tide, the old promises ebbed back over him. What would it be like without Linda? What of their promise to grow old together, loving each other? Again Donald was afraid.

Outside Memphis, with Mi Tu still asleep on the back seat, he pulled over again to give his mind a rest. The car jolted against a curb, waking her up. She’d been dreaming of officials who’d stopped to search her for a visa. “Where is this, Donald?” she asked, wiping the sleep from her eyes.

“The Arkansas-Tennessee border.”

“Oh, Tennessee. You must show me the bluegrass.”

“You must be thinking of Kentucky.”

“I suppose so,” she said, looking out the window. As Donald got out of the car, a truck bearing a load of melons, passed within three feet. Mi Tu watched the truck as it vanished down the road. “Our literature and art,” she said pensively, “are basically for the worker, the people who pick the fruit and drive the truck.” Donald watched as a hawk circled overhead, searching for field mice. He’d lost interest in polemics. Taking Mi Tu’s hand, he placed it on his cheek.

“Mi Tu, what do you feel?” he asked.

“Nothing but your skin.” He placed her hand on the hood of the car.

“What do you feel now?”

“Warm metal.”

“When I ask you to feel something, Mi Tu, you think I mean to grasp it sensuously. That’s because you equate thought with action. There’s no difference for you between the way you feel this car and the way you touch me. You’re committing a mistake Marx warned us of. For me, Mi Tu, thought is feeling.”

That night in Memphis Mi Tu and Donald made love. The next morning they set out early, but both the traffic and the roads were bad and by late afternoon they decided to stop in St. Louis. Donald went out for some food, leaving Mi Tu alone in the motel room. She combed her thick black hair with its grey flecks and thought of China. There’s no turning back now, she said to herself. She had left the People’s Republic for good. Self-criticism had got the best of her, or rather she had got the best of it. In China she was doomed to a part. In America she could be at the heart of the beast, tearing at its throat from within. It would be the ultimate form of self-transcendence. Donald returned with soft drinks and a sausage pizza. Tomorrow morning, Friday, they would set out again for Chicago.

It is Friday night. This is New York City. At 6th and 42nd a man hails a cab. It speeds toward the Lower East Side. Having reached his destination, the man is met by two figures. Together they quickly ascend four flights of stairs to a studio apartment. There, the phone rings. The largest of the three, a woman of twenty-five, picks it up. “Hello. Yes, we’re ready.” She puts the receiver down and grimly smiles at the men. The three of them seat themselves at a table in the center of the room. It has a map and three pads of legal paper on it. The shorter of the two men steps to the stove to put on a pot of coffee. The woman and the other man jot down something on their legal pads. All three drink coffee now and speak quietly to one another.

It is late Friday night. A maintenance crew at Kennedy is cleaning out an empty 747. The last workman to leave the plane reaches into his jacket and conceals three packages under three seats.

To Kathy the idea of changing planes after a six-hour flight from Paris was not particularly pleasing. It was Saturday evening. She was scheduled into Kennedy at 8:45. There she would change for Chicago ninety minutes later.

At 8:48 American flight 122 touches down. Kathy’s aboard. In St. Mark’s Place a woman and two men emerge from a building minutes apart. Arriving at three prearranged points they meet three taxis, each setting of for Kennedy. Kathy is getting off her plane. She is walking around the terminal, looking for an early Sunday New York Times. She finds a copy and sits now in a coffee shop, sipping her first orange juice in several weeks. She sees where The New York Philharmonic is presenting a complete Mahler cycle this week. Donald will throw a fit when he hears about this, she says to herself. Pushing the Times aside, Kathy pulls out a novel from her purse. She opens to the fourteenth chapter:

“The two lovers were on the point of speaking but said nothing. Suddenly they fell sobbing into one another’s arms. They hugged each other’s bodies with an all-inclusive passion, their faces, hot with tears, pressed against one another. The tears streamed down their necks and flowed without cease into the darkness of the room. It was the end of everything, an end to their loving. There were to be no gentle kisses, all was lost. From now on, nothing could be the same.”

Kathy boards the plane for Chicago at 10:10. The passengers have all been checked for weapons, the monitors pronouncing them clean. A tall woman takes her seat next to Kathy over one of the wings. A short man takes a seat at the rear of the plane. The other man sits next to the cockpit.

“Ladies and Gentlemen, on behalf of the crew I’d like to welcome you aboard flight 789 non-stop to Chicago. Please notice as your flight attendants demonstrate the use of the oxygen mask. Should the need arise, it will fall from above; by pulling down on the cord oxygen will be released. There are two exits over the wings, two forward, two aft. Please be sure now that your seat is in the upright position and that your seat belt is fastened. Please observe the no smoking sign. After takeoff smoking is permitted for those in the smoking sections. Trans World hopes you have a pleasant trip.”

Poised at the head of the runway, the engines suddenly rattle the wings of the huge conveyance. The craft picks up momentum, the landing gear retracts, and the great metallic hulk is airborne. Kathy lays her head on a yellow pillow, puts her seat back, and dozes off.

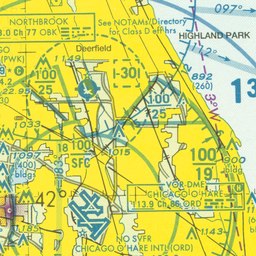

The 747 approaches O’Hare. Kathy has opened her eyes. The hands of the woman next to her are beaded with fine drops of sweat. The woman looks to the back of the plane and drops her arm in the aisle. She looks to the front of the plane and raises it. As Kathy rearranges her pillow, the tall woman reaches under the seat and withdraws a snub-nose 38. No one has observed her.

The wheels of the jet scream on the runway. The accomplice at the front of the plane takes a stewardess by the arm. He tucks a hunting knife neatly under her chin. With three quick strides he reaches the cockpit door, which he opens with a duplicate key. Speaking to the back of the captain’s neck, he informs him, “There has been a slight delay.” The captain looks at the stewardess. “Please pass that on to the passengers,” the man calmly adds. From her vantage point the stewardess observes an armed woman step into the aisle at the middle of the plane. She nods at the captain, who complies with the man’s request.

Now the man holds a revolver at the captain’s head. “Radio and tell them there are people on this plane who will kill if demands are not met.” The cabin lights go on. The 747 pulls into the terminal, but no baggage truck comes to meet it. Relatives and friends wait anxiously in the airline lounge. The door of the plane has not yet opened. A security team arrives to clear the lounge. Curiosity sours into serious concern.

It is 12:59 local time. Negotiations have been completed through the control tower. The plane’s crew and half its passengers will be leaving in 60 seconds for Latin America. At the head of one aisle the tall woman stands with her 38 drawn. At the head of the other aisle her accomplice holds a machine gun. They stare together at a silent, motionless sea of humanity. Suddenly, in row 7 a woman of forty breaks into hysterics, falling from her seat. The man keeps his cool, gesturing to a flight attendant to soothe her.

Now the other man emerges from the cockpit, the muzzle of his revolver pressed against the stewardess’s heart. He waves quickly to the others. He is frantic. Something has gone wrong. Grabbing the stewardess by the arm, he wheels her about. She loses balance and falls to the floor of the compartment. Dropping the revolver, the man draws the knife from his pocket. Twisting her wrist, he lays the hand of the stewardess palm up on the nearest armrest. Without consulting either accomplice he brings down his knife with the force of a bludgeon, severing her index finger. A scream ensues. Blood spurts into the lap of a passenger, who shies away in terror. The man with the knife, still holding her, forces the stewardess to her feet. Stepping directly to the compartment door, he flings it open, pushing the stewardess into the corridor, where police have trained their rifles on the door. They hesitate to fire. The door slams shut. The stewardess collapses on the corridor floor.

The woman with the 38 is perceptibly shaken. She begins to make plans of her own. As the man with the knife speaks heatedly with his make accomplice, she makes her way to the middle of the plane. Looking over the passengers, who avert their gaze, her eyes fall on Kathy. The tall woman grabs her by the wrist, jerking her into the aisle. With a hammerlock, she holds Kathy in front of her, leading her toward the men. “What the hell are you doing?” asks the man with the machine gun.

“I’m leaving,” she replies, blasting him with her 38 in the face. The other man stands motionless. The tall woman opens the door, holding her gun to Kathy’s head. “Back off, you fuckers!” she yells at the cops. “I want a car out front. I want it full of gas.”

Donald and Mi Tu are opening the door to the main entrance of O’Hare. They notice people standing on their tiptoes. There’s a television crew interviewing someone. They walk past the commotion on toward the TWA counter. A woman emerges from a door holding Kathy at gunpoint. She approaches. Recognizing Kathy, Donald ignores the shouted advice of policemen and advances to meet her. The woman shows her gun. “Kathy,” Donald screams as he rushes toward her. The woman’s gun arm stiffens. Drawing a bead, she fires a shot at Donald. Donald dives at her feet. The bullet misses him only to strike Mi Tu, standing directly behind him. It lodges in her heart. Donald has the woman by her foot. She kicks. Her shoe flies off. The policemen draw to fire, but before a volley of three shots hits her, she lets Donald have it in the forehead.

Mi Tu and Donald sprawl lifelessly on the floor. A television camera has videotaped the scene. Kathy, having shaken away at the first shot, stands to one side, breathless. Her wits returned, she rushed to Donald, dropping to one knees beside him. “My God, my dear God,” she weeps.

* * * * * * * * * *

Donald’s widow, still at her parents’ home in Beeville, watches the morning news aghast.

* * * * * * * * * *

January 1977: Santa Fe

Sorting through the closet for Donald’s relics, Linda comes across a photograph of Igor Stravinsky. She holds it up at arm’s length, recalling the day the great composer died in New York City. At the moment of his passing, Nature in her fury had unleashed an horrendous storm.

Underneath the photo she finds a journal of her own, one she’d misplaced several years ago. As she sets it on her lap it falls open to an entry made November 22, 1963: “They killed the President today.”