Chapter 8: An Oriental Museum

Fred emerged from the subway into the place d’Iéna. Washington confronted him, his thin sword, like the needle of a compass, pointed toward the zenith. The women of the USA had given the statue in memory of France’s aid during the struggle for independence. Turning his back on Washington, Fred entered the Musée Guimet. The tourist season over, he was out of work. In the lobby he found himself at the center of a circular Greek colonnade, surrounded in turn by far eastern objects. At the information desk he picked up a sheet of notes. A private collector had founded the institution, ninety years after the Revolution. At his death he had willed it to the state, which had added its own collections. The curators offered everything under the sun for studying the East: music, lectures, archives. Fred decided to look at the things themselves, first.

Where do I start? he wondered. Why not at the top? he said to himself at the bottom of the stairwell. Looking up, he counted four floors. When he reached the third, however, he saw that the highest was barred. Renovation, no doubt. Turning around, he faced a choice. Straight ahead were the photographs. That was out (Fred wanted the thing itself). To the left was the Calmann Collection (he didn’t know what that was); to the right, Japan. He took a right. As he entered the room, the choices again were staggering. A rational person, said Fred to himself, would seize upon something and look. His eye fell on a printed historical summary of Japan, complete with bibliography. Helpful, he thought, but not for now. Looking in the opposite direction, Fred saw a screen and took a step toward it. He was too close to see it. As he started to step back, a label caught his eye. Should he look at the label or step back? The picture wasn’t so attractive. He read the label. “Little screen,” it said, “with two leaves.” He looked closer, hoping to find the subject. “Cat perched on a table.” That’s what I thought, said Fred to himself. He’d learned his lesson.

After he’d looked at a hundred objects, Fred sat down. What about himself? “Where do I belong in all this?” he asked, half out loud. A passing group of tourists heard him and looked the other way. Apparently this was not the place to talk about serious things. Having seen enough works of fine art, he got up and looked at a photo on the wall. It showed a temple overlooking a vast plain, vague mountains in the distance, over which floated a low band of light clouds. Between the near and the far ground the plain was filled with a city, seemingly quiet and peaceful. That, thought Fred, is a question of perspective. He glanced about, comparing the picture with the aristocratic objects in the room. The picture, he decided, represents more of the life of the city. But is the city really in the picture? Fred had begun to think. At least he knew what the city looked like – or did he? And what did he know of its life? (What did the people think, for example?) The more he thought, the less he knew.

Two other photos flanked the picture of the city: on the left, Asura, “one of the eight guardians of the dry lake.” She seemed to have about eight arms; on the right, “Maitreya (Miroka Bosatsu).” A god or a goddess? Fred wondered; at any rate a single figure in wood. Single, or double? Wood, or plaster? Maitreya, or Miroka? Someone knew. Or did they? (Was this a god, or the artist’s conception of a god?) Where was he? Oh yes, what did the people think? (Or what did they think they thought?)

Fred thought this was enough of Japan for one day. He turned and walked through Korea. In the cases he observed reflections, first of himself, then of himself, Japan and Korea. He was looking for something simpler. He remembered a dream he’d had the night before. A person was skipping over an eye. Am I the skipper? he wondered. The eye had been like a globe. Was the person skipping over the globe? Was he skipping himself? He skipped the rest of Korea and gave Thailand the once-over-lightly. He was looking now for himself. In that case, maybe he should leave the museum. But why not find myself in the museum? He wondered if that were possible. Did he have to find himself in everything he looked at? (Why did he have to find himself at all?) Wasn’t he right here? He was back now where he’d started. Picking up some postcards, he skipped out again into the place d’Iéna.

It was 5:00 o’clock Friday morning. Fred, cross-legged, sat on the floor of his room. “What in the world do you think you’re doing?” said Angela, rolling halfway over the side of the bed.

“I’m meditating.”

“Who do you think you are?”

“A Buddhist monk,” said Fred.

“Oh come on back to bed,” said Angela. He got up and made more tea instead. Angela rolled back over. She had broken his train of thought. Fred took the manual off the desk again. Dharma, it was called, blue with white letters.

Light had started coming in the window. Fred was sitting on the desk now and could see himself in the mirror, could see the book open in his lap. “Absence of thought,” it said, “Absence of action.” He knew it almost by heart. “True emptiness is the substance,” he said. His stomach growled. Fred looked around the room. Angela must have forgotten the bread. There was nothing for breakfast. He put the book down and continued. “True emptiness is the substance. All wonderful things and beings are the functions.” The function of emptiness, he thought. He wanted to stop thinking. True thusness, he thought, is without thought. He emptied his mind to receive it. Something began appearing on the other shore. He sat very still and watched. The light was streaming in the window now. Fred looked out at nothing and saw everything.

Traffic had started up. He could hear it coming and going. Inside everything was still. He thought he could hear Angela breathing and began to count, as the breath moved in and out. He could actually see the breath and realized it must be his breath he was listening to. At 7:00 he stopped. Things had come together. A single car went past. Fred blinked. A diamond appeared in front of his eyes, still, suspended in space. It rose up over his head, rising higher as he stood up. He started counting again. But this time the numbers were different. They had stopped going forward and were standing still. Where was he now? Inside the diamond. “The diamond,” he said. It was something he seemed to have made himself. He named it again, and the world coalesced in front of his face.

Where was he now? He had lost track. The cars were still going by outside, and he could still see the light, but it was coming in a different window. “Where am I?” he repeated. Everything was white. He breathed out, he breathed in. The smell was familiar. He was sitting, but not in the place he’d been before. His rear end was resting on something cold. Finally it dawned on him where he was. Reaching up, he pulled the chain and listened, as the water rushed down through the pipes. Plumbing, he thought with satisfaction, a western luxury. He’d started to think again. He walked back down the hall and into the room.

Angela had started to stir. She looked beautiful, her head on the pillow, her eyelids half open. She’d forgotten to take her pearl earrings off. They’d been a present from Fred, who had only known her a week. As she spoke, she smiled.

“Good morning.”

“Good morning,” said Fred rather stiffly.

“You look funny in that robe,” she said. Fred was in saffron, head to toe.

“I suppose I do,” he replied.

“Take it off and come on back to bed,” she said sleepily. Fred smiled. He took it off and stood naked in front of her.

“The coming of Buddhism to China was an event with far reaching results. After a long and difficult period this teaching established itself, joining with the native traditions.” Fred looked up from the book. He was sitting in the Luxembourg Gardens. He and Angela had had a fight over who was going out for bread. “Because you got up before it was light doesn’t make you a holy man,” she’d said. He looked at the book again. “The fundamental tenets are not metaphysical, or theological, but rather psychological.” It was still early, and cold out. “All life is sorrow. All sorrow is due to desire. Sorrow can only be stopped by stopping desire.” It went on about moral conduct. A couple of rich American expatriates walked by with a poodle. The man wore a camel’s hair coat, the woman a leopard skin jacket. They looked at Fred, who was still unshaven, as though he were a bum. The man opened a pack of Chesterfields and threw the wrapper at Fred’s feet. Everything’s a mess, thought Fred. The sky was cloudy. At least a patch of blue had opened overhead. The white jet of the fountain rose to a height of six feet. Fred continued to read. “All things may be classified into five components. The last is conscious thought.” How, he thought, could he remember all this?

He looked up from the book. The gardens were still green. He liked the little border of red, orange and purple flowers. Some of the trees had changed to gold. Over the stones of the Palace flew the red, white and blue. It fluttered and fluttered, refusing to come to rest. “One thing leads to another. This is called the chain of dependent causation.” Fred thought about his mother and the prospect of going back to see her. A man walked by in black. Fred looked at the print again. “The cycle of birth, death and rebirth is the product of ignorance.” He thought of immigration. Maybe that was the answer. “The illusion is that individuality and permanence exist.”

He shut his eyes for a moment, wondering if he could keep on going. It was cold as hell, and he hadn’t had breakfast. What about Angela? Maybe she’d be gone when he got back. And they’d been planning to celebrate his birthday! He was thirty-three today. “Jesus Christ!” he said, looking at the book. “One goddam thing after another.” It was getting colder every second. “The process of rebirth can only be stopped by achieving Nirvana.” Someone turned the lights on in the Palace. Things were getting historical. Attention had turned to India and the second century. Fred skipped along till he came to the Buddha himself. He was awfully cold. Maybe, he thought, I’ll go back and finish this inside. To hell with Angela. The Buddha passed away, ceasing to be a person. Fred’s fingers were almost frozen. He’d reached the theory of the Bodhisattva and the Maitreya. So that was it. He had difficulty following the chain of thought. Something must be missing here. He had skipped the last paragraph. His feet were almost numb. “Whoever thought this up must have lived in a warmer climate,” he said, closing the book. He put it under his arm, rubbed his hands together, and headed back.

When he opened the door to his room, he could hardly believe his eyes. Angela was gone, but everything was spotless. A week’s worth of dishes had been washed, the bed was made, the furniture all arranged symmetrically. At the center of the desk was a note: “Gone to look for work. Love, Angela.” On the bed were two essays, by Angela herself, one for each pillow. On the left, where she slept, “Tu Fu: China’s Gentlest Poet.” On the right, “Li Ho: His Wildest Imagination.” When Fred had picked up Angela in front of the Opéra, he thought she was a whore. She’d turned out to be a student at “Langues O” (The Institute for Oriental Languages).

Fred sat down in his overstuffed chair, an essay in each hand. Feeling had started returning to his feet. On the table beside him lay a biography of Raymond Roussel, open to a passage which described the author’s writing habits. It seems each day he had locked himself in a room with the curtains drawn, fearing that the light from his pen, should it escape, would circle the globe instantaneously and incite a Chinese horde to besiege the western world. Angela had marked the passage with a red felt-tipped pen. Fred tried to comfort himself with an image of the horde having to slow down at least as it climbed over the Great Wall. His anxiety had brought his temperature back up to normal. Putting Li Ho down on top of Ray Roussel, Fred turned to the first page of Tu Fu.

Here was a Chinaman more to his way of thinking. “A large proportion of the poems,” Angela had written, “have war and violence as their central theme.” Fred loved history. Apparently Tu Fu did too. He seemed as nervous a character as Fred. “My anxiety,” the poet said, “rises to inundate even the mountains, with mad swells utterly impossible to abate.” “That’s poetry,” said Fred. Tu Fu also had something akin to what Angela called Fred’s “Bourbon palate.” “Neither of us,” he’d written, “shall refuse to drain many cups. When the dawn comes, we’ll remember our worldly entanglements, wipe our tears, and part – east and west.” Thinking of Angela’s hasty departure, Fred grew a little nervous. His stomach growled. Putting the essay aside, he wondered what to do for lunch. They still didn’t have any bread.

Low on dough, he nonetheless decided to have a decent meal at that Vietnamese restaurant in the rue Dante. “What the hell,” he said, “you only live once.” He would start with the Chui Gio, then Mang Cua, followed by Bun Cha. He’d top it off with some Vit Xao Dua. Annoyed by the length of time the first course was taking, Fred remembered the postcards he’d left in his pocket. He’d bought four: a Gandhâra Bodhisattva and three Buddhas, one from Tibet, one from Burma, one from Japan. He put the Bodhisattva on top of the deck. Like magic the Chui Gio appeared. The grey schist of the statue stood out suavely against an eternal blue background. With the Man Cua he had a blue Tibetan Buddha, surrounded with the rainbow for a halo. “Om,” said Fred approvingly. On closer inspection, however the detail seemed rather fuzzy. A lacquered wood statue from Burma was next, set off by an emerald background. This was more like it. Aware of the danger of sacrilege, Fred glanced about the restaurant, pulling the card in close to his plate of Bun Cha. Fortunately, two rich Saigonese doctors were the only patrons there. Probably Catholic, Fred said to himself. The figure from Japan was nothing but wood, set against a pure white background.

He was really in the mood for China. The tea arrived in a willow ware cup. When he’d finished, he turned it over: “Made in Japan,” it said. This only whetted his appetite for the real thing. Fred paid and headed toward the river. When he’d reached the quay he glanced at Notre Dame. She was facing east but looking west. Fred headed on downriver. The quai St.-Michel gave way to the quai Voltaire. At the pont de la Concorde he crossed over. Ahead of him lay the place de la Concorde, in the center of which rose the obelisk of Luxor, covered with hieroglyphics. Fred was sure there wasn’t one Parisian in a million who could read it, yet everyone seemed to get the general idea. Beyond the place the rue Royale led up to the Madeleine, now a cumbersomely decorated Catholic church. On top of the Naval Ministry a flag flew droopily. Behind his back on the left bank stood the National Assembly, its Greek colonnade a reflection of the Madeleine’s, or rather vice versa. They set it up that way, thought Fred. A large Minerva in black skirt was giving the number 1 sign. There’s certainly nothing silly about the facade of the Assemblée, thought Fred. He crossed the bridge and turned into the Cours la Reine. He passed the Petit Palais and the Grand Palais and took a seat in the Cours Albert Premier for a moment’s rest. The sun was out. The skies were almost blue again. After the cold spell the leaves looked as though they were all about to drop at once. The chestnut trees, as in a formal garden, were evenly spaced. Each leaf, green on the inside, had a border of yellow. As Fred got up to continue, a bird left the branches of every other tree, beginning its flight south.

When he’d reached the place de l’Alma, the avenue du Président Wilson opened like a door, curving up the hill toward the Musée Guimet. The vista was shrouded in mist. Still, thought Fred, I’m getting closer. Sunlight broke through between the buildings. On the left he passed the Museum of Modern Art; on the right, the Musée Galliera, where they were showing Chinese Communist paintings. Entering the Guimet, he strode across the sun-streaked colonnade, until the vision of a Chinese woman, dressed in red and black, arrested his progress. (See Revelations, thought Fred). She was sitting at the information desk. “Which way to the china?” he inquired. “Calmann collection,” she replied. “Third floor.”

Standing in the center of the room, Fred bowed to each of the cases. A guard in blue with yellowish skin yawned and closed his eyes. On the eastern wall three porcelain horses in beige, brown and green were assembled about a vase. Fred stepped forward. Staring into the vase’s cavity, he emptied his mind. Hot from mounting the stairs, he was soothed by the cool T’ang colors, recalling a vision he had had the night before: a large white horse, its arteries and veins standing out in red and blue. He noticed that two of the horses were also looking into the vase, the beige one covered with a blanket of animal skins, the brown one bareback. On a level above them stood the green one, astride it a man, his right hand on the saddle horn, his left cupped to his mouth. Fred stepped closer till the reflection of his face in the plate glass covered the horse and its rider. He thought of Angela, recalling the way that her long brown hair had fallen across her breasts the night before. He stepped back from the figures, leaving them in the same state of fixed repose he’d found them in.

Next he turned his attention to a group of statuettes. The five figures formed a triangle, two of them seeming to step forward as if to meet him. This was reality and illusion. One was dressed in the colors of spring; the other wore the robes of fall. In a corner of the tympanum a girl in a headdress held a drum but refrained from beating it. In the opposite corner a young man strummed the strings of a green lute. At the center a queen-like figure appeared in an ocher gown, its white border continuous with the white flesh of her chest. Her face was pale, her eyes all but closed, the faintest of rouges imbuing her cheeks. Her brows and lips arched in a divinatory mien, an enormous blade-like roach flaring from her head to surmount a lunar coif. As Fred stood and looked, some distance from the glass, his reflection contained the figurine, which floated mid-way between his head and waist. “Pottery,” he said. He’d pronounced the word viva voce. The guard looked up. Sliding toward the exit, Fred thought of Angela.

Soon he found himself in the middle of Pakistan, standing in front of the Gandhâra Bodhisattva itself. “The work combines western art and eastern thought,” said the label. In the face of this mustachioed little man Fred saw the likeness of himself. Streamers flew from the figure’s stone headbands, flattening out against an oval dish, which appeared behind the head. Fred sat down on a bench and stared at the figure’s navel. Animal earrings complemented the human amulet around its neck, on which a man and woman were seated at a table across from one another. As Fred studied the sensuous curve of the garments, he felt something graze his arm. Another figure, this one in a saffron sari, had seated herself on the bench. Fred blinked and continued to gaze at the navel, but the air had grown perfumed. He sensed that the face next to him had turned toward his. Turning himself, he looked at the girl. A golden pin glistened above a delicate nostril; a mark of saturated rose glowed between her brows. He blinked and looked again. She was offering her profile, gazing now herself at a Bodhisattva on the other side of the room. Its hands were in its lap, palms extended upward. Fred looked about the room. His eyes fell on the form of Kali, her hair flaming skyward, one leg folded, the other reposed on the body of a miniature man. A single strand of jewels coiled about her neck, leading Fred’s eye downward as it passed between enormous rounded breasts on its way past her navel to a garment wrapped about her loins. Something happened. Fred felt an absence. Turning again, he saw that the saffron robe and its occupant had vanished. Passing through the space that she had occupied, his eye fell to the middle of a flaming circle, inside which Shiva danced. Of his six visible limbs only one came to rest, touching the place of the enchaining of souls.

When he got back to his room there was another note from Angela, this time nailed to the door: “Found work. Sailing for Beijing tonight. I’ll miss you.” On the floor of the hallway lay The History of China. It was a present from Angela. Finishing off a bottle of Lacrima Christi, Fred cried himself to sleep.

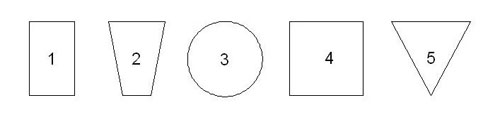

When he woke up, he recognized another day. It couldn’t be all that bad, he consoled himself. He considered having a cup of tea, but that would remind him of Angela. Instead, he went out for coffee, heading down the rue de Rennes. When he reached the boulevard St.-Germain, he stopped to buy a magazine and settled into a seat at the Café aux Deux Magots. He sat on the eastern sidewalk, the sun shining brightly in his face. The waiter bowed, left, and returned with a cup of coffee. The sugar lumps were wrapped in a paper with red and black designs. One Chinese man with an O on his chest was talking to another with an o inside an O. Feeling empty himself, Fred opened up his magazine: “How to Read Fate and Character in Facial Features according to the Method of Ancient Chinese.” The article began with an illustration of five basic faces:

Number 1, it said, was the head of state. Number 2 represented the artist. Number 3 exhibited a total lack of ambition. Number 4 was a stubborn, implacable person; number 5, the intellectual or dreamer.

Fred scratched his square jaw and realized that he’d forgotten to shave. Two Chinese girls went by, one rectangular, one triangular. A French girl with a white circular face went by in a blue Mao jacket, rouge on her cheeks. A square-faced African went by in a black shirt, white pants and red jacket. The article went on to analyze the faces of famous people: Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, Sheila and Li Hung Chiang, “the Bismarck of Asia.” Two German tourists next to Fred got up and left. Henry Kissinger, Brigitte Bardot and a Japanese Samurai were under discussion. A small, sensitive French woman with trapezoidal features went by. Jean-Paul Belmondo was analyzed, the author finding resemblances between the actor’s mug and the comic masks of the ancient Chinese theater. Jackie Onassis, Lincoln and Golda Meir were taken up. Two Oriental girls went by dressed like French girls. One had frizzy hair and wore a pale blue smock. One bore a slight resemblance to Michelle Morgan. Jackie Onassis, the article said, was an amorous woman, in need of a permanent masculine presence. Her large nose indicated that she was very rich. Lincoln, it said, had the appearance of a president of war. Golda Meir had a fish’s mouth, like Brigitte Bardot. Both, the author said, had overcome barriers in order to find success.

It was all lost on Fred, who couldn’t stop thinking of Angela. What in the world had made her take a job in Beijing? He’d probably never see her again. He picked up the sugar wrapper and remembered he hadn’t read the essay on Li Ho. Having paid the Mandarin price for his coffee, he went back to his room.

Li Ho was an altogether different story. Like Tu Fu he was obsessed with history but had tried, it seemed, to escape from it all by mounting into the air and viewing the earth from an astronomical perspective. Fred skimmed the essay, looking for some reflection of Angela’s state of mind. The poet, according to her account, was possessed by a dark angel, though he put all the colors of the rainbow into his poems. The colors didn’t always match, Angela said: “Emerald fire,” “blood-red towering peaks,” for example. Her essay concluded with a dramatic statement. “Poetry’s crazy,” she said. “History’s what counts.” She had ended by praising Li Ho’s sense of the tyrannical power of time and events. Fred felt sorry for Li, but sorrier still for himself. What had Angela meant by leaving? It didn’t make sense. As he maundered, he noticed The History of China. Putting the book under his arm, he set off for the river. He wanted time to think it all over. He’d give history one more try.

He found a bench down by the river under the Palais du Louvre. The sun was shining warmly, and it made him feel lazy. Opening the book, he realized he couldn’t possibly read it all today, but he turned to the table of contents anyway. The first chapter took up “The Chinese Earth.” Quite a mouthful, Fred thought. Though, he reflected, I suppose it’s a natural place to begin. The wind was kicking up leaves around his feet. “The Expansion of a Pioneer Race,” read the title of Chapter II. Sounds like America, he thought. When he studied the map, however, he saw what the author meant. People were pleasurably strolling alongside the river. “Feudalism and Chivalry.” A beautiful Chinese girl went by, her head held high, shoes and lips bright red. Heading west, she looked down at Fred.

The water of the Seine was sparkling in the sun, turning pieces of caught debris into brilliant specks of light. The next chapter took up the sages of former times. Fred was feeling quite warm now and took off his coat. He leaned back, closed his eyes, and listened to two old men who had sat down next to him. A third old man approached, addressing the other two as “fishermen.” He too sat down on the bench, making four of them all together. Fred opened his eyes and looked at the contents page again. “By Iron and by Fire.” An enormous tree spread its branches far out over the waters. The old men talked on, about America vis-à-vis France. A noisy machine started up on the opposite bank. Chapter VI took up someone called “The Chinese Caesar.” Fred glanced at the dates, looking up from the book, past the tree, in time to see a barge poke its way upstream under the pont Royal. The next chapter dealt with the question of empire, the one after that with the Pax Sinica. A mottled pigeon, more white than grey, fluttered down in front of Fred. It picked over seeds that someone else had left behind. A heavily loaded barge passed downstream, a handsome pleasure boat in its wake. “Europa,” said the large white letters on its side. A man in a yellow shirt was washing the deck. The old men continued to converse. The sun had declined behind a large branch of the tree.

“The Triumph of Letters.” Fred perked up, thumbing the pages for signs of Tu Fu and Li Ho. Apparently they hadn’t yet arrived on the scene. A black pigeon joined the marbled pigeon. Together they picked up the grain. Another old man had arrived, wearing dark glasses. There wasn’t room for him on the bench, so he stood as he talked to the others. The next chapter took up “The Road of Silk.” Fred was amazed by the flood of names and events. An enormous bateau mouche passed by, heading downriver. Fred could almost hear the tour guide pointing out details to German tourists clustered in the prow.

Fred closed the book, leaving his thumb inside. Two lovers had seated themselves on the cobblestones. Fred thought of Angela. Together three old men arrived and took turns shaking hands with the ones already there. One of them had a brilliant red leaf in his hand. The sun had fallen further now and flickered through the leaves. The water, set in motion by the passage of the boats, was splashing with light. Chapter X took up the Revelation of the Buddha. Fred ticked the page and read a sentence or two. A boat from the boat-school passed on its way downstream. The light had changed now so as to catch in the still-green leaves of a tree on the opposite bank. Fred observed a small dark figure walking over the pont Royal from north to south. Framed by the bridge’s portal, the lovers embraced, entwining their arms. The girl reclined on the stones, her long orange hair the color of leaves overhead. A Japanese girl in a bright red sweater descended the steps from the street and walked past Fred’s bench, heading upstream.

Chapter XII took up the splendor and decadence of the Han. As the sun set on the opposite bank, it quickly grew colder. The chapter touched on the glories of art. Fred noticed the name of another Parisian museum concerned with the Orient. The text dealt with the epic of three realms, the great invasions, the low empire, and other matters. A young man had sat down near the base of the tree on the other bank. It dwarfed him. He gazed out, watching the boats go by. One made a huge furrow on the surface of the river. A girl in maroon boots went by and caught Fred’s eye. As he looked back at the river, the furrow had healed. A boat called “The Danube” followed, making another.

Fred followed the drift of the chapters on through to the end, meditating as well on recent history. He thought of ticking a page that mentioned Li Po, but the subject made him think of Angela. Two of the old men on the bench got up and left. Only one now remained. Fred looked at him, welcoming the chance to talk. The old man asked if he were Breton. Fred said yes. The conversation took up provincial life in France. Soon France was being compared with other countries. The old man spoke of life before the war and after; of Adolph Hitler, Napoleon, Charles de Gaulle; of America, and the future of Europe; of Russia; of China, before and after the Revolution. Fred should have guessed that he was in for a monologue. Finally the man turned to the question of his own pension. Fred gazed over his shoulder and watched, as the boats and the girls and the dogs on leashes kept going by. It had gotten cold. He thanked the old man for his conversation, got up and left. Walking upstream, he crossed the river and headed home.

“As for the Bodhisattva and the Buddha, they have secondary cause as their character.” Fred was reading again. “The cause of understanding as their nature.” He’d had a good night’s sleep for a change, but now he was feeling horny. “Direct cause as their substance.” He imagined Angela sitting on the deck of a slow boat to China. “The Four Broad vows as their power.” He still couldn’t figure why Angela had left. “To hell with her,” said Fred. He vowed he’d find himself another broad. “To hell with Nirvana,” he said.

That night Fred had had a puzzling dream. It consisted of nothing but the number 23. Two three, he said to himself. Then he remembered Angela. She was twenty-three. But that didn’t seem to explain it. The dream wasn’t about Angela. “Two and three,” he said, adding them together. He tried subtracting one from the other. He multiplied the two, reversed them, everything he could think of. It was all very puzzling.

What’s the best place to pick up a broad? he wondered. In front of the Opéra? It was Sunday morning. Not much action Sunday morning. He looked at the desk. Alongside Dharma lay his Michelin Guide. He had it almost memorized. “Wait!” he said, opening the guide: “Isolated Points of Interest!” He scanned the page for some place open on Sunday. The Père-Lachaise cemetery? No, that wouldn’t do. (It reminded Fred of Jim Morrison.) The Marché aux Puces? He scratched his head. Running his finger down the column he came to an item at the bottom: the Musée Guimet! “Of course,” he said, recalling the reading room. Why sit around here? He put on his coat and set out for the subway.

Fred entered the Métro under a sign that read “Place Maubert-Mutualité.” “La Mutu,” he muttered, glancing at a female student getting on the train. He sat down across from her, reading her eyes for signs of incipient love. She blinked and looked down at the floor. The first stop was Cluny. Fred felt distinctly middle-aged. At Sèvres-Babylon the train stopped, jerking forwards and backwards. Here we go again, he said to himself, as they headed off. At Lamotte-Picquet he followed a sign reading “correspondance” to a line that led to the place Charles de Gaulle. The new train crossed the river over the pont de Bir-Hakeim. (It reminded Fred of Last Tango in Paris.) Again he thought of Angela. Maybe it was just as well she’d left.

Settling into a chair at a long table, Fred opened a book on Oriental philosophy. “India, China, Japan,” the subtitle read. He looked around the room. It was filled with scholars. An ugly Indian girl in thick glasses was translating Chinese manuscripts into a western language. A Japanese student sat across from her, his face almost hidden by a stack of reference books. An English gentleman, wearing a hound’s tooth jacket, was using children’s crayons to color Xerox copies of Persian manuscripts.

Over the librarian’s desk sat the Buddha. Behind his head light streamed in from the East. Over his shoulder the expensive grillwork of balconies on a large apartment building were visible. The statue had once been freshly painted gold, but the curatorial staff had allowed dust to accumulate on its head, shoulders, legs and open palms. Fred pushed the book aside. There weren’t any girls in the room worth looking at. He shut his eyes. Breathing in and out, he began to count to himself. One, two. Three, four. When he reached ten, he opened his eyes again. A blond girl of twenty had entered the room and taken a seat. Fred closed his eyes and counted again. When he reached twenty, he opened them once more, in time to see a sixty-year-old black matron taking a seat across from him. He closed his eyes and counted again. Twenty-one, twenty-two. Fred liked the even numbers better. Twenty-three, twenty-four. Again he thought of Angela. Twenty-seven, twenty-eight. He’d begun to slow down. Twenty-nine, thirty. Again he heard footsteps and opened his eyes, directing his gaze at the table top. Someone, pulling out the chair on his left, was taking a seat.

At first, all Fred could see was her long black hair, flecked here and there with a strand of white. It reached almost down to the floor. Then, as she pulled it back behind her ears, he saw her profile. She was Chinese. Though there was nothing in front of her on the table, still she was smiling, smiling it seemed at the empty table top. Fred continued staring out, sensing her presence by means of peripheral vision. She was very close. As he looked ahead, he sensed a change in the atmosphere. His eyes began to fall involuntarily, until they reached a point at the edge of the table. She, it seemed, was now also looking at the edge, which served to connect them in time and space. Fred moved slightly in his chair, placing his feet more firmly and resting his forearms on the table. As he did so he sensed another movement. In the corner of his eye he noticed the woman placing her forearms on the table. Fred felt an urge to count again. Thirty-one, he said to himself, moving his lips and breathing in. Thirty-two, he said to himself, letting the breath escape. Thirty-three, he whispered, drawing in his breath. He’d inflated his lungs to their fullest extent. At the height of the breath, he noticed another movement. The woman had now withdrawn her right forearm and turned her body so as to face him in contrapposto. She was looking directly at him. “Thirty-four,” he said out loud, releasing his breath and looking directly at her. “Quarante,” she said. “Forty,” Fred repeated, translating into English.

The clock struck twelve, time for the museum’s midday closing. The librarian rose from his desk and asked that the scholars leave. “She” and Fred for an instant gazed into one another’s eyes. Then, getting up, they left the room together.

“Fred,” said Fred, by way of introduction, as they passed through the open grillwork into the hall.

“Mi Tu,” she said in turn. They descended the stairway together. “J’ai faim,” she said (I’m hungry), looking at Fred.

“Me too,” said Fred. He looked at her and smiled. Leaving the museum, they turned to the right. Soon they had reached the place Victor Hugo, where they looked for a restaurant open on Sunday. Finding a brasserie, they shared a sandwich. As they sat side by side, Fred took Mi Tu’s right hand, holding it in his left. When they finished eating, he kissed her. A black man in a green suit walked past the restaurant window. On the back of his jacket a red and yellow patch said “Black is Beautiful.” A French girl walked by wearing a Boy Scouts of America shirt. She looked at Fred and Mi Tu with disdain. As they got up to leave, Fred turned to Mi Tu.

“What do you want to do?” he asked.

“Have you seen the show of Communist painting?” Fred wanted to answer, “Yes.” He had something else in mind. He paused. Mi Tu looked him in the eye.

“No,” he said. Before he knew it, they were approaching the museum. Forty, said Fred to himself, as they walked along under the autumn trees. Forty minus twenty-three is seventeen. It was Fred’s favorite number.

They entered the Galliera by way of a luxuriant garden filled with emerald grass. Continuing through a circular court, they passed by works of decadent art on their way to the main entrance. In the exhibition hall the ceiling and walls were draped in green. Before the pictures stood an introductory text in large white letters. Standing together to read it, Fred noticed that Mi Tu began at the bottom, where friendship between the French and Chinese was spoken of. The next to last paragraph mentioned the class struggle. Fred followed Mi Tu’s eyes upward. They passed Mao, Lin Piao and The Great Cultural Revolution, arriving at last at the district of Hu. Fred looked at the text. “These people come from Northern China,” he said.

“Moi aussi” (me too), she said. It proved a fitting confirmation of what Fred suspected.

Together they toured the collection of works by the peasant artists. From one point of view the pictures were quite good; from another point of view they were quite bad. “They represent a lot of work,” said Fred. Mi Tu smiled. At least she has a sense of humor. Everyone was happy and working. Having, himself, lived in a state of unemployment, Fred got part of the message. “I’ve been out of work,” he said, “for a whole month. What do I have to do? Move to China?” Mi Tu gave him a friendly smile.

The people in the pictures, Fred noticed, all looked very happy. He looked at Mi Tu; she was smiling again. Fred had never seen so many smiles. The animals were healthy, the trucks were all full, the anvils hot, people were attending meetings at night, kids were learning their lessons, adults were working together, soldiers were fighting side by side. The people’s hearts were all in unison. So what if the pictures were done by amateurs. Fred looked at Mi Tu. They’d reached the end of the show. He wanted to give her another kiss. As they stepped out the door, he looked at her. “Where,” he asked, “do we go from here?”

“Where do you want to go?” she asked in reply.