Chapter 5: Stravinsky Ballet in Two Scenes

“‘America first,’ said Washington.” Kathy read part of a travel poster aloud and speculated: “I bet it’s as cold now as it was then.”

“You mean it’s as cold now as it was when Washington crossed the Delaware?” Elizabeth doubted it. The snow let up as the two window-shopped in town. Lace-up boots, furs and of course skis were on display. Many items were marked half price. Kathy spied a very handsome bracelet that she “had to have.” She and Elizabeth walked back to the lodge. Next semester seemed far away. By the time they had gotten back to the room the snow had started again.

Elizabeth’s parents had taken Kathy and Liz off for a wonderful week in Colorado. They bought computer-type watches for both girls. Linda, alone in Sante Fe (Donald was off in Chicago at an academic conference), had gone to several parties. On the way back from this meeting Donald stopped to see his dying father in Kansas. However, the last night that he was in Chicago Linda received what she thought might be a drunken telegram reaffirming “faith in our love.” Cleaning the house the next day she found a piece of black cloth that Donald had worn as an armband when Igor Stravinsky had died. She recalled a friend once having asked him who it he felt most like. “Stravinsky,” Donald had replied. In the afternoon Linda planned her evening of television entertainment.

For dinner she made lasagna. She was really in the mood for spaghetti, but she hadn’t any. What the hell, she thought, lasagna’s like spaghetti – flattened out with more cheese. After supper she watched TV. This was educational. “As you will recall,” intoned the stately personality, “Benjamin Franklin had departed for France. Here he would be received most cordially.” The voice continued, revealing the plot: “In fact Franklin would become the idol of Paris society.” This was a program Linda could sink her teeth into. Her taste tonight, however, ran more to Italian. An opera by Verdi would have been her preference. When the play was over she turned to another channel, where a show about the martial arts was in progress. In the middle of an ad for America’s numero uno soft drink Donald called. “It’s June in January,” he sang. The levity, however, dropped from his voice as he told Linda that his father couldn’t last much longer.

Lying under the warm quilt Linda imagined what it was like to live in a state of suspended animation. She fell asleep, thinking of frozen vegetables. At 5:30 am the alarm went off. Anticipating an omelet, Linda dragged herself out of bed. Having finished her morning’s work, she decided to spend the afternoon tidying up some papers tucked away at the back of the bedroom closet. When she had pulled it all out she found three boxes of letters, short stories in manuscript and a stack of postcards. Carefully she refilled a box with Donald’s work, occasionally glancing through a story or stopping to read a title: “At the School for Angels,” “From the Hotel Antarctica.” From beneath a heap of sheet music she pulled out the program notes for Donald’s piano sonata:

The entire sonata is a mirror of my brain. The underlying organization of the piece is dualistic. It reveals a war of epic scope, irrationality versus reason, the religious versus the secular, atonal versus tonal. The work expresses love for the melodies of Brahms, Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky because they are based on dualism, that is, diatonic melodies are played off against a restless chromatic background. This is the greatest device of nineteenth-century Romanticism.

Laying the program notes aside, Linda sprawled out on the living-room floor. She recalled what Donald had been like as an undergraduate. When they were juniors she had asked him what he wanted to be. “A Saint,” Donald had said. Everyone else she had known at the time had aspired to be a scientist or lawyer. When Linda returned to sorting papers, she discovered a journal that Donald had kept before their marriage, along with another one she herself had kept at the same time.

Donald Bunge, Journal

September 29, 1968

We slipped into the Victorian house, afraid of disturbing someone, though none of my relatives had been living there for many months. The house smelled of tea and cigars. I showed Linda the dining room table, where Grandma had brought me milkshakes. The kitchen was still as I remembered it. Next to the stove, propped against some apothecary jars, was a farmer’s calendar. On it was a drawing of a quarter moon. The piano I used to practice on stood at the center of Grandma’s study. Through the great windows of the study Linda and I watched an autumn sunset. As we pressed our faces to the glass, two butterflies landed on a lilac bush in the garden.

. . . . .

I made a fire in the fireplace, while Linda fixed us hot cocoa. There before the blaze we undressed. As I kissed her I heard an owl, which must have been perched close to the house. The firelight revealed Linda’s soft breasts. Her marvelously strong back made a graceful arc at the moment of orgasm. Our bodies wet, we lay motionless with exhaustion. She felt as I felt, or seemed to. We both smiled; our thoughts were blank. And yet I knew that blankness is not emptiness.

. . . . .

I watched Linda combing her long thick hair. She thought I was reading. Suddenly her brush came crashing down on the dresser. The next thing I realized she was waving my copy of Wittgenstein at me, telling me, “If you want this back you’ll have to get it.” Well, get it I did. We made love for the fourth time within five hours. Afterwards, she set the alarm on the table beside our canopy bed and put out the tiffany lamp.

. . . . .

This morning, after I’d finished my journal entry, we talked about the prospect of another hard day’s drive. When we walked out to the car together, we found that during the night leaves had filled the front seat of the car. We said our good-bye to the grand old house. I turned on the radio for the weather report. It began to snow, turning, within minutes, into a storm. As we drove through the blizzard Linda scrawled my name on her frosted window.

. . . . .

It has all seemed fantastic, yet here we are. There has been no deceit! She seems beyond deceit, beyond deception. These last few days have been completely without pain. And yet, if Freud is right, Jason seeks death to end his sickness. Everything is like the last puff on a cigarette before the firing squad.

Approaching his twenty-fourth birthday and the completion of his master’s degree Donald was confronted with the inevitable question: what was he to do for a living? There was no job market for the budding young writer. Just as things were looking their darkest, he came into some unexpected money: a three thousand dollar prize from a short story contest. “Eureka! Fat City!” said Donald. With the money he spent the summer visiting the USA: a Zen farm in California, Linda in Washington, DC. He had hoped for Satori. By the end of September he was washing rice bowls. Fatigued and lonely Donald rushed to Linda on bended knee. In three weeks they were married.

Linda Finley, Journal

October 1, 1968

I cried all day. Could not stop the death images coming. Don and I talked for an hour on the phone. He came over early evening and held me for a long time. Stayed till I fell asleep.

October 2, 1968

This morning I found a sonnet Don left me on the coffee table. Such a bright, priceless gift. It assuages my fear.

. . . . .

We aren’t sure what we’ll do after the wedding. We haven’t any idea where we’ll live or how we’ll survive. Donald wants to live in solitude. But even that has its price. I’ve offered to support both of us, so he can write. What he desires and needs. I have no idea what kind of job I can get – secretary? teaching? (I don’t relish either). Whatever happens I must remember Don’s writing. The writing comes first. I want us to be happy and live our lives out together in love.

Linda put the journals back into one of the boxes. Next she came across a notebook Donald had kept in Paris. It too was in the form of a journal. It seemed to date from 1967. Linda took a seat on the sofa.

I spent my first day in Paris walking through a hot frozen album of postcard snapshots. The scattered white buildings. The perfectly diminishing perspectives of pillars and arches. Roman statues and fountains. The three structures in Paris that I fell in love with at once and without reservation were the Grand Palais, the Pont Alexandre III, and the Eiffel Tower. All three come to us from the same decade, and each is a magnificently entertaining example of Art Nouveau.

Linda flipped the pages and came to an entry headed “Illiers”: “The ghost of Proust haunts the place. For some reason I could swear the town as it is now is the same town Proust described. Is Proust still here?

“A walk through Illiers is a journey into my childhood. Everything is exactly as I dreamed it would be: dark storm clouds over fields of unharvested wheat, water lilies, fishermen, berry bushes. It is all Paradise. I look for Proust. I miss him in the landscape. Is he here now? Does he still remember?”

The sunlight had grown faint. Linda switched on a floor lamp near the sofa. As soon as her eyes had grown accustomed to the light she began to drift into the past again, back into the first apartment she had lived in with Donald. She recalled images of the furniture, a brass bed they had later sold when they bought a larger one. She let out a deep breath.

While it was still light enough, Linda decided to go for a walk. She buttoned up her loden coat, pulling a muffler tight around her neck, and set out for Canyon Road, which was once a trail, in use long before the Conquistadores came on the scene. Now local artists and craftspeople kept small shops there. More than a quarter of a century ago Los Ciños Pintores had founded an art colony there.

Fresh snow lay loosely packed on the ground as Linda made her way up the Canyon. In alternate glances she looked at the natural setting and the curio shops. She crisscrossed the street, browsing at the store windows. Enough variety here to please any tourist, she thought: clothing and gifts from Morocco, Turkey and Ecuador; desert cactuses; tropical plants in handcrafted pots; gold and silver jewelry. Sculpture, paintings; furniture; Hopi kachina dolls; Spanish rugs and fabrics; handmade pottery fashioned in small but productive studios.

As Linda kept on walking her nose got cold. She tried warming it up by blowing on it, cupping her hands over her mouth and exhaling warm breath. It seemed to work. Each time her nose got cold again, she cupped her hands again. The sky was overcast with puffy snow clouds. Still the air was clear. Linda admired the vivid colors. They must have something to do with the atmosphere, she thought. As she was admiring the clarity a little grey-haired man hurried toward her on the sidewalk. He was looking behind him. Before Linda could step aside to avoid him, he bumped his arm against hers, dropping one of his books into the street. Startled, they looked at one another. As both bent over to pick up the book, their heads collided. “Oh, I’m sorry,” the little man said. “How silly,” Linda replied. She bent over, this time by herself, and picked it up. Handing it to him she glimpsed the title: Four Quartets. The little man seemed very embarrassed. Putting the book back under his arm, he glanced at his wristwatch. “Holy shit. I’m late,” he cried, forgetting Linda as he rushed off.

Near the end of Canyon Road she stopped to stare at a small yard filled with snow. Someone (children from the size of the footprints) had stamped out “Kathy + Ron.” As she watched the kids, who ignored her, Linda recalled an evening long ago. It had been early winter, the first snowfall. She had just come back from a late seminar. In the large quad in front of their graduate housing, she had written with her feet, “LINDA LOVES DON.” She had had to pull Donald out of his chair to make him look out the window.

. . . . .

It’s 11:00 pm. Linda is fixing herself a cup of café au lait. Fuck, she says to herself, feeling unsatisfied after an afternoon in the cold and a dark evening. She thinks about her sex life, diverting herself with self-made images of all the different positions and situations she’s fucked in. What an odd sentence, Get fucked, she says to herself. I guess love-making isn’t the same as fucking. But how could “get fucked” mean anything bad? It’s all screwed up!

At 12:15 she goes to bed. She thinks of a story Donald once told her. It’s about the second time Donald had gone to visit Stravinsky. Right after he’d gotten his B.A. he went to California. When he arrived at the front door two Slavic maids were polishing two large door knockers. Donald asked if Mr. Stravinsky were home. They told him he had left for New York. Disparaged, he mentioned the great distance he’d come. One of the women sympathized: “What can you do? What can you do? Nothink. Nothink,” she said. Pulling the satin quilt up to her chin, Linda began to cry.

Kathy and Liz had a busy day on the slopes. Elizabeth came close to breaking an ankle, and Kathy had a close call with a postal employee on vacation. After supper with Liz’s folks, they retired to their room, reading magazines as they listened to the radio. Liz discovered Buckminster Fuller by way of an old Rolling Stone. “He seems to be in favor of getting the maximum from the minimum,” she told Kathy. “Do you suppose that’s how Russian novels are written?” Kathy wondered. “By making a lot out of a little?” “Not exactly,” Liz replied.

Later on they decided to monitor each other’s sleep. Liz was already feeling drowsy, so Kathy would observe her, watching for rapid eye movements. In about an hour Liz’s eyes began to move under the lids. Kathy jostled her. “What was it about?” she asked.

“I was fucking,” said Liz.

“Who?” Kathy asked.

“Donald Bunge,” said Liz. “And we, and we were doing it in his office. No, it was outside! We did it both in his office and outside. Wow!” She blinked slowly. “Let me go back to sleep.”

“Sure, Elizabeth, sure.”

Still, Kathy couldn’t just let Liz wallow in wishful delight. Dreams are private, she thought. But, she felt cheated too. So, as Liz was finding the place where she’d left off, Kathy tried to annoy her by reading aloud. She began with an old issue of The New York Review of Books,which had a review of Gershwin’s Reader’s Digest. It was entitled “The Final Days of Louis XVI.” This had more effect on Liz than Kathy realized.

Elizabeth’s determination helped her back to sleep. Trying, however, to conjure Donald up again, she saw herself instead in the act of reading an antique manuscript. As she concentrated, the word at the top of the first page came into focus. “January,” it said. She continued to look. Sentences emerged, the way a secret message does when held in the right light. “Damn! This is remarkable,” she thought. “Let’s see. That’s a date. It says “January 20*.” What’s that by the twentieth? An asterisk.” As Elizabeth dreamt, the words dissolved into narrative.

JANUARY 20* The Historical Society met again this month, under singular circumstances. First, the meeting was by invitation only; secondly, not everyone was invited; finally, our gathering took place in a retreat for the insane. Those invited, at the suggestion of the president, agreed to take separate coaches. The weather was monstrous. Icy roads made our travel hazardous. One could not conceive more dismal surroundings than those in which we assembled this morning.1

. . . . .

On the way to the asylum I read an interesting article. The work, which is entitled “The Dialogue of Unreason,” maintains that deranged language can only be confronted by the absence of language. In other words, if someone were to converse with you in a deeply confused way, you should simply ignore him. This struck me as curious, for I myself have a friend, a philosopher, whose utterances have never made any sense to me at all. Yet, because he cannot speak, should I be silent?

. . . . .

The caretaker led us down a narrow, windowless corridor, which smelled like burnt sulphur. “Current practices,” he said, looking back at us over his shoulder, “do not allow the use of chains and dungeons. Take, for example, Monsieur Louis.” He paused in front of a large oak door, looking into our faces somewhat apprehensively. “This, of course, is highly irregular . . . .” He hesitated. Then, as though overcoming a final inhibition, he added, “However, seeing that you are scholars . . .” He opened the door on a man whom we recognized at once.

“It pleases me,” said Monsieur Louis, “to see that you have accepted my invitation.” Several of the members traded astonished looks. There had been no invitation. “As you can see,” continued the King, “from my depleted condition, I have been deprived of certain comforts which would make your visit more enjoyable. These are indeed trying times. But please be seated. Forgive me if I seem a bad host.” The slightly overweight gentleman made sure everyone had a chair. “If only I had access to my wines,” he continued. “Well, let’s not dwell on these deprivations. May I offer you tea?”

“I think that would be agreeable,” said the chairman, accepting on behalf of the other members. “Were Cléry here,” said Monsieur Louis, “he would of course attend to the serving of the tea. But, as I am without servants, the serving will be done by me. It’s strange that someone” – he glanced at those of us seated on his right – “who was once served by a nation is now served by himself.” Professor Higginbottom placed his arm on my chair and whispered, “If only he were master of himself!”

“Monsieur?” Monsieur turned toward us, “you have something to say? Did I overhear conversation?” Higginbottom leaned further forward. “Right,” he said. “I was saying I’d be more than glad to serve tea.” Monsieur Louis smiled at the professor’s effort to dispose of a sticky situation. “You are too kind,” he said. “However, it is not my habit to call upon my visitors to serve themselves. My captivity has forced me to accept many things. But bad manners are not among them.” He made tea and offered bread.

Someone tossed a bit of leftover crust into a small lit fireplace. The host grimaced. “I was once informed,” he said, “by a certain grandmother that since little boys cannot make a loaf they should not waste one. It is a shame in times such as these to waste food.” His brow wrinkled. “That of course is merely the opinion of a ‘tyrant.’ At least this is how I am addressed in the streets.” He walked over to a desk cluttered with papers – newsclippings and the like. “Here” – he held up a broadside – “I’m referred to as a ‘perjurer’ and ‘a monarch unworthy of the throne.’” He waved the sheet of paper for us all to see. “This one” – he picked up a clipping and held it above his head – “calls me an enemy of the public! How, sirs,” he continued, seating himself again, “am I to respond to these ingratitudes, when I myself am spat upon, when my wife is told her heart would be ‘excellent stewed’?”he sighed, pausing to scan the faces of the members, who were all regarding him intently. “Gentlemen, the substance of my intention was clear from the beginning. My opinions were and always will be consistent with the public weal.” He paused again, his eyes fluttering for a brief moment.

“As for the departure of the royal family from Paris, I can offer you nothing new. It was not our aim to abandon the French people. I have explained before the purpose of our removal to Montmédy. That location was the most propitious for the disarming of neighboring countries. Had I demonstrated my liberty, the allied powers would have had no cause to avenge me.” Once more Monsieur Louis sighed heavily. “The result would have been a great saving in blood and tears.” Having enunciated these last words, the poor man, possessed by unspeakable evil, collapsed against the back of his chair and fell silent.

What sort of cruel joke is this? For what reason had we come? Is this simply an eccentric amusement? These were a few of the questions I entertained as I reflected on the spectacle before us. Only toward the end of our stay did things begin to fall into place. Yet there were no answers to my questions, only impressions, impressions and facts. That most of our academic knowledge is arrived at by the assimilation of words from a page has long been an unquestioned axiom of my life as a scholar, for whom the pursuit of truth is confined to books. In this my colleagues concur. It is the rational processes of learning that we value; the irrational we disregard, if not disdain, however much we must confront it in our day-to-day experience. Surely the true function of the mind is to suppress it, to suppress it and control it. History – or so I have been taught – is an orderly, on-going process. When water is applied to the paddle of a wheel, it moves. So do men traverse a temporal distance, influenced by forces which, collectively, we term “history.”

Our gathering today placed this teaching in jeopardy.

Induced, no doubt by the reflections of the Monarch, one of our party raised again the topic of The Flight of the Royal Family. Nodding with approval, my bald and graying companions gave ear once more, as the demented King consented to narrate the matter. “Very well,” he said, as he cleared his throat, “I trust you will not mind if I have occasion to refer to my notes and journals. At present I’m in fact engaged in writing a chronicle. It will bear the title, ‘From Riches to Rags.’ I’m told such an undertaking will fetch a handsome sum.” Shuffling the papers on his desk, Monsieur Louis muttered to himself, “Where is it then? Where could it be now?” Lifting a single finger, he placed it on the manuscript. Settling in the chair, he cleared his throat again and began. His voice resumed its former tone of authority.

“It was the thirtieth of June, 1791. At 11:00 o’clock on that night a glass coach waited in the rue de l’Echelle. Mme de Tourgel, my son, and my daughter were in that coach. My son was clothed as a little girl. He lay under Madame’s gown at the bottom of the carriage. Their coachman was a Swedish nobleman, one Michael Fersen. They were to be joined by the Queen and myself. An hour passed before this rendezvous occurred. In her gypsy hat the Queen, with her misguided courier, roamed the environs of the pont Royal, until Luck discovered us (though the Queen aided Lady Fortune by using her imagination to inquire the way of passers-by).

“The crack of a whip signified our departure sometime after midnight. Small animals fled before us in our path. During this journey I went by the name of Durand and was attired as a valet de chamber. Mme de Tourgel journeyed in the guise of the Baronne de Korff, while the Queen played the role of governess to the Baronne’s two girls. Three gardes du corps accompanied us as “servants.” Before we reached Étoges the next morning, I can assure you many doubts and fears beset me. Gazing upon the passing moonlit landscape, recollections of prior events occurred to me, taking the form of dreadful apparitions; my wife and children running terrified through the halls of Versailles; the slaughtered gardes du corps; crowds of half clothed women demanding my return to Paris; people armed with pikes shouting “Vive la Nation!”; heads of the slain guards; the key to the city of Paris. I imagined three thousand voices, as they cried for bread and the Queen’s liver. All these things, all from the Fall, from October of ’89. The thought of them, as I said, preoccupied me during our departure from Paris on that early June morning.

“Yes, we fled,” said Monsieur Louis, reflectively, sipping his tea. “For you see, in October of ’89 we were left little choice but to return to Paris. I agreed then to take up residence in the Louvre. The mob, wishing to tear the Queen to pieces, escorted us to Paris, singing their insults and curses the entire way. ‘String the nobles from the lampposts,’ they cried. ‘The baker, the baker’s wife, the baker’s little son, all to Paris they come.’ Bringing up the rear of that procession was a veritable army of Parisians. At that time our retinue included the Princesse de Chimay, the ladies of the bed-chamber, other servants, plus a hundred deputies. I made it clear to the people that I would go to Paris, but I wouldn’t be separated from my wife and family.

“The advance guard, having left Versailles several hours before us, paused at Sèvres. There they forced a hairdresser to powder and fix the heads of the slain guards. When we arrived at the Hôtel de Ville, there were no arrangements to accommodate us. My wife’s eyes were filled with tears, and she could hardly speak, after that awful journey. Normally the journey from Versailles to Paris would have taken but two hours. That day it required four.” Louis paused to adjust his wig, which had slipped midway down his forehead. “A few days passed. It was decided that the Queen’s presence in Paris needed proving. With that aim in mind she was invited to a play. To which invitation she replied, “The sight of the heads of loyal guards should not be followed by celebrations.” Louis patted his wig, gently, with both hands, causing a little puff of powder to rise over his head.

“After our return from Versailles, everyone responded as if I had been dead, were now rejuvenated and restored, restored to the people of France. The consensus had it that by leaving Versailles I would attend to matters of state and insure that good be done. It appeared then that the day was saved. Lafayette again became a royalist. The insurrection had ended. Oh, what false hopes these were!” His eyes had begun to tear. “The weight of deceived hope burdened my departure from Paris.” Images of June 1791 invaded his mind. “October” –October 1789 – “held promise,” he said in a chastened voice. “June’s promise was escape. In October I accepted from the Mayor of Paris the key to the city, at which time I recall saying” – Monsieur Louis glanced up from his notes and spoke the words from memory – “‘It always gives me pleasure and confidence to be among the good people of Paris.’ Afterwards” – the narrative resumed – “afterwards, in a loud voice, Bailly, the Mayor, repeated my words –slightly altered – to a cheering crowd. The Mayor’s rendition left out the word ‘confidence.’ Whereupon the Queen took occasion to correct him: ‘The people of Paris,’ she said, ‘have no doubt the King’s return pleases him. It is, however, important that they know he comes with confidence.’” For a flickering instant, Monsieur Louis’ cheek blushed with rouge. Quickly his pallor returned. With a scarcely audible sigh he concluded: “If I came to Paris with confidence in October, then in June I left it dubious.” He drained his cup of tea.

“After October my duties as the first servant of the law were defined for me. I was expected to sign treaties when authorized by the Assembly. I was to make declarations of war and direct military forces. The coining of money was also among my delegated tasks. I could freely choose my ministers and dismiss them. Finally, it was in my power to oppose any laws passed by the three legislative assemblies. And yet, toward the end this power proved but an illusion. Soon it became clear what the assembly wanted. They did not wish to rule through me, they wished to rule me!In a list from that epoch” – he gestured toward his papers, the scholars nodding – “my name appears . . . last; ‘the Nation,’ it reads, ‘the Law’” – he paused, his hands arrested in mid-air – “‘the King.’ Effectively,” he said sadly, “the King of France did not exist.” Again the scholars nodded.

“Oh yes, there were shouts of ‘Long live the King,’ as I swore to uphold the Constitution. And ’tis true, the Queen – enthusiastically! – held our son at arm’s length before an elated National Assembly. But don’t forget” – he tapped the palm of his left hand with a rigid right index finger – “do not forget what the people sang at the Festival of Federation.” Humming a tone, he set the measure:

‘Our deputies you should have seen

Some of them very sulky,

Draggle-tack and bulky,

From bathing with a muddy Queen.’

Several members had lit large cigars. All continued to listen attentively.

“‘Why,’ my son once asked, ‘why are people angry with you Papá? Papá, how have you hurt them?’ I told him people must not be blamed for their hatred, explaining that a few wicked men were responsible. To which he replied, ‘Papá, did they not love you?’ Only children see truly the inconstancy of the world. A pity that manhood destroys such simple childish reasoning. And when I signed the decree imposing the oath to Nation, Law and King on the clergy, I thought again about my son’s questions. Forced into that position, I should rather have been King of Metz than King of France.”

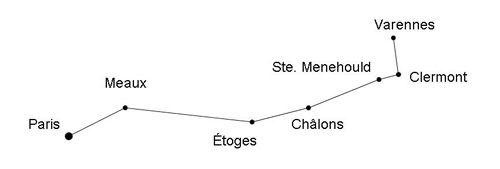

Our host’s account had diverged, as it were, from the intended path and stood in need of some direction. Through the grey smoke the voice of one of our members emerged: “Could you, sir, please give us more details of The Flight itself?” Monsieur Louis indicated his willingness and stepped up to a small blackboard, where he sketched the following map:

I reminded Monsieur Louis that in his previous comments he had reached Étoges. With the completion of the scheme he continued.

“Nothing happened to us the morning we reached Étoges. In the afternoon we had reached Châlons. There, our horses refreshed, I became impatient and left the carriage, accompanied by the Queen. No sooner had we walked once about the coach than two townsmen addressed us. They seemed pleasant enough. Yet this short chat quickly drew a small crowd of well-intenders. As we made ready to leave, a small boy handed me a gift for the Dauphin, to be presented upon our next meeting. It amounted to a box of dominoes, though no ordinary dominoes were these, but fashioned instead from bits of polished marble taken from the walls of the Bastille. It was a curious relic of the Revolution. On the lid of the box an inscription read: ‘Stones resurrected from arbitrary injustice.’ I found this unusually touching.

“Tense moments, however, awaited the remainder of our journey. Outside Châlons mounted troops were to have met us. No troops were to be found. We waited nervously there till eight of the evening. Moving along we reached Clermont, whose streets were lit by the torches of rioters. As we passed slowly through the center of the village, we at last glimpsed the troops. The unruly mob had prevented them from mounting their horses. Recognizing me, a faithful soldier approached the carriage. ‘Make haste! You have been betrayed,’ he said cautiously. This news did not set well with us at all. With great anxiety we proceeded. However, despite the disturbance, as our coach bore us toward Varennes, I slept soundly.

“I had the strangest dream. I was sitting on a floor somewhere writing a word over and over. First I would write the letter z, next t, then y, and finally x. When I had finished, I proceeded to write them again. I’m not sure, but I think the word described something. As I continued to write, an elderly man came into the room, carrying with him a small bundle of twigs. He sat next to me, dropping the sticks, picking them up, and dropping them again. The gentleman appeared to be of foreign origin. From his manners I judged him to be Chinese. When I inquired what it was he was doing, he replied, ‘Looking for patterns.’ I expressed a wish to see some. ‘Will any of the patterns do?’ he queried. ‘Yes,’ I said, ‘but is it possible to see them all?’ ‘Very well,’ he replied, ‘Here’s one for you. The King of France wears a wig.’ ‘What does that refer to?’ I puzzled. ‘I haven’t the slightest,’ he answered, smiling.

“Somewhere outside Varennes our carriage was violently halted. The jolt awakened everyone instantly. My first thought was that all was lost. It turned out that we had merely stopped to meet a courier who would take us to fresh horses. I would say we reached the entrance to Varennes at about 11:00 o’clock. Our men escorted us to a chateau where it was said horses awaited us. When we entered the village our carriage was beset by armed men again bearing torches. ‘Halt! Halt!’ Their cries surrounded us. They insisted the occupants of the carriage identify themselves. ‘Madame de Korff and her family,’ we said. ‘What in the world is the meaning of this?’ ‘Remove yourself or we shall kill you’ was their terse reply.

“Under duress we entered the mayor’s house. The mayor, who by profession dealt in candles, was dressed in nightcap and dressing-gown. In vain I tried to appear inconspicuous, for you see, in these small quarters hung a portrait bearing, as chance would have it, a striking resemblance to one of the travelers. My identity revealed, the citizens threw themselves at my feet. ‘I cannot permit you to pass,’ said the Mayor. ‘Pray return to Paris. Do not abandon your people.’

“The following morning I was presented the decree of the Assembly, delivered by an aide-de-camp to Lafayette. Though he showed me respect and courtesy, he fulfilled his duty by arresting me. To no avail did I point out there was no King to be arrested – the French, you see, no longer had a King.”

. . . . .

No sooner had we thanked Monsieur Louis and begun to take our leave than he turned on his heel, apparently having lost all interest in his visitors. As I left the room, I noticed him seated at the desk, his wig slightly askew, completely absorbed in his papers. When we had reached the hallway, the caretaker said to me in a whisper, “Poor devil, thinks it’s Christmas. Louis XVI wrote out his will at Christmas. So he writes a will. Unlike the real King, however, Monsieur Louis writes one every day.”

. . . . .

Reconstructing the special meeting of our Society has caused me to reach two important conclusions for the understanding of his history. First, to bring particular facts together into intellectual universals is not to reveal a logic of events. Nor does such a process indicate that civilization is progressing toward fulfillment. Second, there can be no mechanics of history, because it is precisely the unreasonableness of things which makes them so.

1 Editor’s note: The following narrative draws heavily upon unpublished papers of E.M. Hardwigg in the collection of Mme Jules Roy. The editor would like here to record his graditude to Mme Roy for the many kindnesses she extended in the course of the research. He is also indebted to the staff of the Bibliotèque Nationale, especially to Mlles Jannick and Aubépine for their indefatigable assistance in the restoration of many mutilated texts. Professor Hardwigg’s geological adventures are well known. Nonetheless, the editor feels it appropriate her to note the fact that much of the professor’s hypothesis concerning the earth’s interior was formulated on a ship which never left her dock.