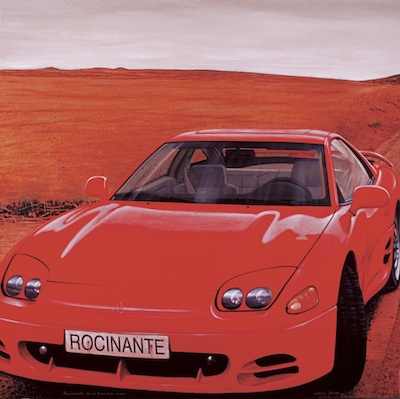

Antoni Miró, “Rocinante de la Mancha” (oil on canvas)

4

Crossing the Guadiana River, on the route from Sevilla to Faro, we enter Portugal. The country rose to European prominence in the 14th century. The landscape darkens into a quiet pastoral beauty. Most notably under King Diniz, who greatly strengthened its defenses by rebuilding a string of castles along the Spanish border. The almond trees are blossoming. Portugal’s first serious foreign adventure was João I’s sortie across the straits of Gibraltar in 1415 to capture Ceuta in Morocco. The topography becomes hillier and rockier. He took with him three of his sons, including the youngest, Dom Henrique. The skies too, in the late afternoon of a day on which sunshine was predicted, have also darkened. It was he, later styled Henry the Navigator, who established the School of Navigation at Sagres. It begins to drizzle. And initiated Portugal’s great maritime exploits. Author overnights in Faro.

Faro was an important Moorish city that was captured by Alfonso III during the dying days of Arab rule in Portugal (Martin Symington, Essential Portugal). Author, arisen early, unable to find a cup of coffee at 7:00 am, has returned to his hotel and taken a seat at his escritorio to read the guidebooks. Faro continued to flourish until 1596, when, under Spanish occupation, it was sacked and burnt by the British; then, in 1755, it was again destroyed, this time by the great earthquake, more famous for having reduced Lisbon to rubble. He peruses too a copy of yesterday’s Portugal News, a weekend newspaper in English. It was originally believed that Revala had slipped over the border from France a matter of hours before his arrest in Lisbon, but it has now been uncovered that he first spent some time in Spain. Author will continue on today by train to Setúbal, a predominantly modern city.

According to the French press the Algerian killer had been detained a week before Christmas for theft in Madrid, only to be released after several days in captivity. Madeira was discovered in 1419 and the Azores in 1427. It was at this time that the man, wanted internationally for three brutal murders, decided to leave Spain and head for Portugal. Gil Eanes rounded Cape Bojador on the West African coast in 1434. Author gazes out across a narrow alleyway at a house covered with blue, green and orange tiles, remnants of the Moorish occupation. Henry died in 1460 but his work continued with Bartolomeu Dias rounding the Cape of Good Hope in 1487. The original stone facings of its windows are intact. “These tiles cover the walls of cottages and palaces alike” (Lonely Planet Guide). Vasco da Gama finally discovered the sea route to India ten years later. On a clothes line: black pants.

At 7:30 am the sky has begun to lighten. Pedro Cabral landed in Brazil in 1500. The morning clouds are a faint pretty gray, touched with the sun’s pink. Portuguese Fernando da Magalaes (Magellan) was captain of the ship that set out in 1519 to circumnavigate the world, though he sailed under a Spanish flag. The birds have awakened; a cock is crowing. The spirit of the era is recorded in Luis de Camõens’s epic poem Os Lusiadas, which jubilantly and magisterially describes Vasco da Gama’s voyage of discovery to India. But there is still no one on the streets of Faro. In 711 the armies of Moorish Africa launched a devastating amphibious attack upon the Iberian Peninsula. Red-haired, freckled and smaller than most boys his age, an eleven-year-old resident of Almada has masterminded a number of law-defying crimes and continues to scare the living daylights out of most adults.

The tide of Islam, which proved irresistible for several centuries, was to leave its indelible influence upon the population and countryside of the Algarve. The police know who he is and where he lives and that he is the perpetrator of crimes such as the theft of a municipal bus, residential burglaries, armed robbery, pick-pocketing and vandalism, yet he still roams and rules the streets of Almada. “The Moors also gave Algarve its name: Al-Gharb, or Western Land.” The last crime that he was known to have committed is the theft of a Mercedes Benz off a showroom floor. “The long struggle to expel the Moors began at the end of the 8th century, but it wasn’t till the 12th that significant gains were made.” The theft of this expensive vehicle was carefully executed. “The Muslims were routed at the Battle of Ourique in 1139.” The boy hid in the showroom and waited for the staff to close for lunch.

“The reconquest of Chelb, 50 years later, was a major military operation.” He grabbed hold of the car’s keys and quickly drove off before anyone could react. In 1415 a Portuguese fleet assembled on the river Tagus in Lisbon for a scrupulously planned defeat of the Moors on their home ground. During his joyride through Almada, with police cars trying in vain to establish the whereabouts of the stolen vehicle. Crossing the Strait of Gibraltar, the Armada attacked and seized the North African city of Ceuta. He was involved in an accident with a Fiat Punto. An illustrious member of the expedition was a young nobleman, half Portuguese and half English, the son of the King João I and his wife Filipa, daughter of the Duke of Lancaster. This did not stop the young thief. The king, delighted by the valor of his hitherto bookish son. He calmly switched the license plates of the two vehicles.

Rushed to the Algarve to welcome him back at Tavira. Much to the dismay of the confused onlookers at the scene of the accident. And awarded him the title of the Duke of Viseu. He drove off once again, continuing his tour of Almada. Later he received other titles: Knight of the Order of Christ, Governor of the Algarve. Until he abandoned the Mercedes in the residential area where he lives with his mother. But most remember him as the man who changed the map of the world: Prince Henry the Navigator. At 7:40 am, still in search of a cup of coffee, author is out into the street, where a painter is already at work white-washing the side of a stuccoed building, across from the Jardim Manuel Bivar. A woman is cleaning the windows of a juice shop, but when author knocks on the door, she shakes her head to indicate that it is still too early. The Shell station is open. Might they have something to drink?

Al-Idrisi accepted the king’s summons and soon settled in Palermo, where the pair began a fifteen-year collaboration that would produce one of the masterpieces of medieval geography. They have a soft drink machine, but author does not have enough change. The great silver planisphere was stolen and melted down not long after its completion. But distinctive lapis hand-copied editions of Al-Idrisi’s Map of the World survive, as do some partial sets of associated regional maps, ten for each of the seven traditional world climates. The Café do Coreto is not yet open for business, a woman perusing its horario on the door. Al-Idrisi and his team of scholars depicted the inhabited world as occupying one full hemisphere, or 180 degrees stretching from Korea in the East to the Canary Islands in the West. Author finds a fruit stall open in the Rua da Misericordia, within it a glass case with a can of Coke on a shelf.

These last confirmed islands preceded, in the Islamic imagination, the inky black waters of the Atlantic, feared as the Sea of Darkness. But it is 100 escudos and the merchant has no change for a 500. Ten degrees on each side were allotted to the Encircling Ocean, thought to surround the earth’s landmass. She will take 75 escudos in coins instead; author may pay her the rest, she says in Portuguese, another day. Al-Idrisi drew on a wide range of sources, including the classics of Muslim geography and cartography, for his knowledge of Africa and Asia. Refreshed at last, his thirst for caffeine satisfied, author continues. For information closer to home he relied on his career as a traveling scholar, supplementing his classical education with the accounts of European travelers, merchants, diplomats and members of Roger’s large navy. We pass the second archway of the old walled city, and the Atlantic Ocean appears.

Al-Idrisi’s great geographic compendium, dated January 1154, is extant as well. The sun itself has at last become visible, having emerged from behind the clouds. By order of the king, the work was given the fanciful title, Amusements for Those Who Long to Travers the Horizon. The formerly gray band of clouds above has turned white, orange and gold. Understandably, the Arabs commonly referred to it simply as Kitab Rujar, or the Book of Roger. Behind author there is a sudden whoosh of sound, as the municipal fountain begins to shoot forth at 8:00 o’clock. Al-Idrisi’s Book of Roger offered the medieval West the most comprehensive descriptions to date of the peoples, lands and cultures of the seven climates. The seaside scene, however, is undramatic: over a fence, a single railroad track, beyond which a narrow band of water. This was the case for Africa in particular, a region that Arab sailors, traders and adventurers knew well.

Fishing boats, red rimmed, blue hulled, are moored in the shallow bay. And beyond geography, into ethnography, zoology and other fields, The Book of Roger informed its readers of the practice of cannibalism (on the island of Borneo), the intelligence of elephants (in Africa), the caste system (in India) and Buddhist beliefs (in China and elsewhere). A siren sounds; church bells ring. These were doubtless part of the urge to be comprehensive. The source of the siren now becomes visible: an ambulance. Al-Idrisi’s Map of the World became important too for the future of western cartography and navigation, because it drew on the scientific traditions of Caliph Al-Mamun and the researchers at the House of Wisdom and helped to introduce them to a whole new audience. Author, arisen at 5:00, after three hours of failing to find a cup of coffee anywhere on the streets of Faro, heads for the center of town, the old city. It is 8:15.

Western imitations of Arab maps began to appear by the 13th century, including a work of cosmology by the Italian philosopher Brunetto Latini. At last he locates a café devoted to the actual production and serving of cups of coffee. No Dante scholar had noticed the possibility that the Italian poet might have been influenced by Islamic sources, until the prominent Spanish orientalist Miguel Asín Palacios published his invaluable Escatalogía Musulmana en la Divina Comedia (Madrid, 1919). The German Scholastic Albertus Magnus also produced a basic world map around this time. The conclusion reached by Asín Palacios is that Dante derived his conception of the Divine Comedy from the story of the Prophet Muhammad’s transportation on his night journey from the Ka’ba to the temple at Jerusalem and from his ascension to heaven, together with the Islamic legends woven round this story.

It depicts Baghdad and the southern Iraqi city of Basra but not Paris and could only have been based on Muslim sources. A dog on the doorstep growls as author tries to enter. One such clue lies in the marked improvement throughout the 14th century of European depictions of the Indian subcontinent. “Conflict for the Future” (the heading for a letter to the editor in The Portugal News). The coffee and the pastry are both warm. “Sir, It seems to me that Christianity is not so much a religion as a cultural umbrella, under which western values reside.” Likewise western depictions of the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf and Siberia, long known among Arab merchants as Balad Al-Aibir. The dog enters behind another customer, threatening to bite him too. “Its religious content has become bland and dull, no longer a defense against the onslaught of a vigorous, dynamic, demanding Islamic faith.” A veiled woman enters.

These representations attained levels of precision unthinkable without reliable models to copy. The dog does not bother to harass her. “The Muslims are growing stronger, younger and more vociferous in a Christian, aging, liberal Europe, where having a new car is more important than having a new child.” European works also displayed accurate depictions of South Asia and the East coast of Africa long before western travelers had made their way to such remote regions. A woman in her early 30s sits at a table supervising her daughter as she does her homework. The Muslim understanding of Africa and the Indian Ocean was particularly important for the future of European exploration (The House of Wisdom: How the Arabs Transformed Western Civilization). “If we don’t wake up, we will not be able to watch the movies that we like to see.” The ten-year-old has Teletubbies on the back of her jacket.

For in overturning classical notions that the Indian Ocean was landlocked, it showed that circumnavigation of southern Africa was not impossible. “Because the Muslims feel that to do so offends their creed.” The dog looks up menacingly at author, who at last is enjoying a cup of coffee and a pastry. More important for the West than any specific borrowings from the Muslim geographers, however, was the general Arab intellectual legacy. A woman enters in a short haircut. “Women slowly will be pushed back to where they were a hundred years ago, and churches will be replaced by mosques.” The Muslims also offered practical advice, to Vasco da Gama, for example, who was guided to India by a Muslim map and perhaps by a Muslim pilot. The dog growls and heads off after two men in the street. Christopher Columbus also benefitted from the work of the Arabs, from the Latin translation of their mathematical geography.

At 9:04 am we are about to leave Faro by train for Setúbal. Portugal’s greatest calamity struck on All Saints Day, November 1, 1755. Our coach lurches, as another is added. With the candle-lit churches crowded, the earth shook. The clock moves to 9:05. It crumbled ceilings and walls. Our coach lurches again, and we are off. Fast-spreading fires killed between 50 and 60,000 people in Lisbon. Fires are burning at trackside, as old ties are consumed. The epicenter of the quake is thought to have been just off the Algarve coast, possibly between Faro and Tavira. The sun shines serenely on orange tree, lemon tree, stucco facade. Witnesses claimed to have seen a fiery volcano erupt from within the sea just before the first jolt. We bounce again on our way out of town, in view of the sea, the cause of these recent tremors unknown. A nightmarish tidal wave swept as far as four miles inland (another guide).

We are slowing down for our stop in Loulé. The 1755 Lisbon earthquake, Spanish and French invasions. Two lively girls, probably drunk, have entered the train. Which preceded the loss of its largest territorial possession abroad, Brazil. It is not quite clear whether or not they are prostitutes. Resulted in both the disruption of political stability and economic growth. An unforgettable Portuguese king was Sebastian (r. 1557-1578). As well as the reduction of Portugal’s international status as a global power during the 19th century (“Portugal,” from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia). Who is said to have been deeply moved by the Algarve. Shouting and gesticulating, the girls change from seat to seat. After the overthrow of the monarchy in 1910 a democratic but unstable republic was established, then replaced by the “Estado Novo” dictatorship. The scenery and climate reminded him of North Africa.

The girls accost the conductor, who leans into one of them. This compounded the king’s compulsion to conquer Morocco for Christianity. They leave the coach. After the Colonial War and the Carnation Revolution of 1974 the democracy was restored. Now they return, conversing loudly. The country handed over its last overseas provinces (Angola and Mozambique most prominently). One of the girls has much cleavage showing. At the turn of the 19th century political tremors spread throughout Europe from the epicenter of Paris. The conductor follows them into the center of the coach, then returns to the end of the coach to complete his duty, punching tickets. The last territory, Macau, was handed over to China in 1999. The French Revolution worried the authorities in Portugal, who banned radical books and fads. The girls laugh, pleasantly disrupting the stolid bourgeois atmosphere.

The situation so upset the melancholy Portuguese Queen, Maria I, that she handed over power to her son, the Prince Regent, João. The train horn sounds twice. Portugal is a developed country and it has the world’s 19th highest quality of life. In 1807 the royal family fled to Brazil, as Napoleon’s soldiers invaded Portugal. The two girls yell at each other, in increasingly high-pitched tones. It is the 13th most peaceful and the 8th most globalized country in the world. Another 19th century tragedy was a war of brother against brother, literally. One of the girls, bare midriff between her black tight pants and black bustier, screeches at the other. It is a member of the European Union (it joined the then EEC in 1986). Competing with the sound of the train’s horn, which continues to sound at each crossing. During the Reconquista, Christians recovered the Iberian Peninsula from Moorish domination.

Pedro IV, the absentee monarch holding the title of Emperor of Brazil, and his brother, Miguel, called The Usurper, struggled. The girls stand to adjust their clothing. With British help the liberal forces defeated Miguel’s navy off Cape St. Vincent in June 1833. One girl gets up and walks the length of the coach. Then Pedro’s expeditionary force arrived in Eastern Algarve. She turns back smiling, before opening the next coach’s door. And marched all the way to Lisbon. Our coach is filled with the acrid smell of coal smoke. Afonso Henriques officially declared Portugal’s independence when he proclaimed himself King of Portugal on 25 July 1139, after the battle of Ourique. Bloodshed haunted the last few years of the monarchy. He was recognized in 1143 by Alfonso VII, king of León and Castile and in 1197 by Pope Alexander III. The shorter girl is wearing a wide silver necklace.

In 1249 this Reconquista ended with the capture of the Algarve on the southern coast, giving Portugal its present-day borders, with minor exceptions. She now returns from the other coach. On February 1, 1908, the royal family was riding in an open carriage through Lisbon’s immense riverfront plaza, the Terreiro do Paço. A black girl passes, smiling at author by way of reference to the two white girls’ antics. When an assassin in the crowd murdered King Carlos with a shot to the head. In 1348-1349, like the rest of Europe, Portugal was devastated by the Black Death. Laughter breaks out from the white girls, again reunited. Another marksman in the conspiracy killed the heir to the throne, Prince Luiz Felipe. As we arrive at Albufeira, the girls, in their original seats, are cavorting wildly, raucously squabbling, causing other passengers to approach the center of the coach with trepidation.

In 1372 Portugal made an alliance with England, the longest-standing alliance in the world. The conductor returns to quiet the girls down, unsuccessfully. In 1382 the King of Castile, husband of the daughter of the Portuguese King who had died without a male heir, claimed his throne. Another young middle-class woman picks up her bag and leaves the second-class coach. An ensuing popular revolt led to the 1383-1385 crisis. Pulling out of Albufeira, we barely glimpse the beach. A faction of petty noblemen and commoners, led by John of Aviz (later John I), seconded by General Nuno Álvarez Pereira, defeated the Castilians in the battle of Aljubarrota. It is a town of white fishermen’s houses. This celebrated battle is still a symbol of glory and the struggle for independence from neighboring Spain. During the whole course of our travel along the coast we have yet to have a full view of the Atlantic Ocean.

Albufeira’s pock-marked cliffs rim a roomy beach, says the guide book, but we cannot see either. The Treaty of Tordesillas, intended to resolve the dispute that had been created following the return of Christopher Columbus. On a sunny summer day, says the guidebook, the tractor hauling fishing boats must maneuver among the sunbathers in bikinis and impromptu soccer games. Was signed on 7 June 1494 and divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between Portugal and Spain along a meridian. Two sheets, hanging on a line above a white cottage. West of the Cape Verde islands by 370 leagues (off the west coast of Africa). Are catching the early-morning, late-winter sun. In 1498 Vasco da Gama finally reached India and brought economic prosperity to Portugal and its then population of 1.5 million residents. It is still only 9:30 am, the girls continuing to laugh tumultuously.

Albufeira’s cliff-top position and labyrinthine street layout had military significance during the mid 13th century. Rocky outcrop fills most of the fields as we pass under the modern highway and continue on up the coast. Entrenched in this easily defensible spot, the Moors were able to hold out against the main drive by King Alfonso III to expel them from Portugal. Now almond trees break out in glorious white blossoms. In 1500 Pedro Álvarez Cabral discovered Brazil and claimed it for Portugal. They appear as though herded together in small fields defined by low stone walls. Ten years later, Alfonso de Albuquerque conquered Goa, in India, Ormuz, in the Persian Strait, and Malacca, now a state in Malaysia. Suddenly the landscape changes drastically into a large, broad plain. Thus the Portuguese empire at once held dominion over commerce in the Indian Ocean and the whole South Atlantic.

We are slowing for our next stop, Tunes, but seven minutes away according to the red neon scroll of information. The Portuguese sailors set out to reach Eastern Asia by sailing eastward from Europe. The conductor having failed to subdue the two girls, three more staid middle-aged passengers get up and leave the coach. Landing in such places as Taiwan, Japan, the island of Timor. Both the girls stand up. They may have been the first Europeans to discover Australia and New Zealand. They lean out the coach window to yell at departing passengers. The Treaty of Zaragoza, signed on 22 April 1529 between Portugal and Spain, specified the antemeridian to the line of demarcation specified in the Treaty of Tordesillas. Finally they get up and leave the coach themselves, voluntarily. The sudden end of seven centuries of monarchy brought a great deal of confusion and crisis to Portugal.

The white houses of Tunes rise from the seashore up a gently sloping hillside. All these facts. The town is too small to be listed in the guide. Made Portugal the world’s major economic, military and political power from the 15th century to the beginning of the 16th. During the next hour we are scheduled to pass through many more small towns and villages. Presidents and prime ministers, trying to give direction to the new republic, hopped into and out of office with discouraging frequency. From Fronteira to Setúbal will be another hour and a half, but with far less frequent stops. In 1916 Portugal went from bad to worse. The screeching of the girls can be heard from the next coach down. When the Germans threatened the African territories, Portugal entered World War I on the allied side. Our eight-minute stop in Tunes is almost over, our coach having acquired three or four new passengers.

Portugal’s independence was interrupted between 1580 and 1640. With all the problems compounded, democracy never stood a chance. Because the heirless King Sebastian died in the battle of Alcácer Quibir in Morocco. Our train must back out of Tunes. Philip II of Spain claimed his throne and so became Philip I of Portugal. A revolution in 1926 put the country in the hands of a strongman, General António Oscar de Fragoso Carmona. The girls return, at least to the passageway between the two cars, where they toss pieces of metal onto the floor. Although Portugal did not lose its formal independence, it was governed by the same monarch who governed Spain. We have changed tracks and stopped again. Briefly forming a union of kingdoms, as a personal union. Some six years later his brilliant finance minister, António de Oliveira Salazar, took over the reins.

The shorter girl sticks her head into our coach. The joining of the two crowns deprived Portugal of a separate foreign policy. Two other girls in our coach have begun to laugh at the antics of the two crazy girls. And led to involvement in the Eighty Years War being fought in Europe at the time between Spain and the Netherlands. After Frontiera we will continue on to Ermidas-Sado. After more than 30 years of being dictator. Then to Alcácer do Sal. Salazar was felled by a stroke. Monte Novo Palma, which we will reach at 12:09 (author reading from the train schedule). In 1968. And arrive finally in Setúbal at 12:43. War led to a deterioration of the relations with Portugal’s oldest ally, England, and to the loss of Hormuz. Our departure from Tunes has been delayed unconscionably, enlivened only by the crazy girls having at last joined author in the composition of his narrative by speaking into his tape recorder.

From 1595 to 1663 the Dutch-Portuguese War primarily involved the Dutch companies invading many Portuguese colonies and commercial interests. Simple Portuguese author had learned to understand a little of on the Amazon. In Brazil, Africa, India and the Far East. But this babble is incomprehensible. Resulting in the loss of the Portuguese Indian Sea trade monopoly. And, unfortunately, impossible for author to transcribe. His successor, Dr. Marcelo Caetano, began tentative plans to relax government control. The first girl speaks again into his tape recorder, the second commenting on what she has said. Portugal began a slow but inexorable decline hastened by the independence in 1822 of the country’s largest colonial possession, Brazil, where in 1807, the Prince Regent João VI, under threat of Napoleonic invasion, had shipped himself off to, establishing in Rio the capital of the Empire.

♥

Having reached Setúbal, with its donkey rides and hot-air balloon trips, author sets out instead across a beautiful park, with its blue tables and yellow plastic chairs arranged outdoors, beneath blue Pepsi-Cola and yellow Lipton iced tea advertisements. “An industrial town,” the Michelin guide calls it, “a port and a tourist center,” mostly for visitors from nearby Lisbon. The well-tended grass is green, the trees are tall, the people seem happy. “The town’s commercial activities are various:” In the park author encounters five high-school girls, four of them sitting on a bench together, one leaning in behind them, all giggling over a romance magazine. “Cement, paper pulp, automobiles, chemicals, fish and shipbuilding.” We have left Spain for good. “And development of the salt marshes on either bank of the Sado.” Out of the Parque do Bómfim we enter into what appears to be Avenida Alexandre Herculano.

“‘Shtoo-bahl,’” the Lonely Planet tells us, “is how the town’s name is pronounced.” It is a gorgeous, mild, sunny afternoon. “The human occupation in the municipality’s territory remounts to pre-history [sic],” the Costa Azul brochure tells us in its tortured English, “having been found in several places from times since Neolithic [sic].” A makeshift structure on the ground floor of an old house represents itself as “Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus,” “Igreja” being the Portuguese word for “church.” “The urban nucleus is intensively occupied since Iron Age [sic] and registers a special increment with the Romans, who take possession of an important commercial entrepôt, animated by [sic] the Mediterranean peoples, in contact, along the river, with mining centers in Alentego.” The English Institute, a three-story building, next to a video game emporium called “Teenager,” is flying the flag of England,

Author relinquishes the guide books for more direct observation, interspersed (again) with another kind of observation by Peter Godfrey-Smith, in his Theory and Reality. here from Chapter 15, “Explanation,” beginning with Section 13.1, “Knowing Why.”

Heading toward the Old City. What does science do for us? We quickly come upon Romanesque battlements. In Chapter 12 I argued for a version of Scientific Realism. Which descend down a modern, graffiti-covered stairway. According to which one aim of science is to describe the real structure of the world. We examine a building that turns out to be a church. But it is also common to think that science tells us why things happen. Neither our map nor the building itself offers us its name. We learn from science not just what goes on but why it does. Its interior is quite extraordinary: Science apparently seeks to explain as well as describe.. Columns, twisted ropes of stone, ascend 30 feet to ogival arches. So we seem to face a new question. Above the altar the white walls of the nave are covered in diamond-shaped tiles, black and white. In what sense does science give us an understanding of phenomena.

We return into the sun-bathed modern plaza, whose walls are covered with graffiti: As opposed to mere descriptions of what there is and what happens? Large messages in gray (outlined in pink); in blue (outlined in white and black); in (un-outlined) silver. The idea that science aims at explaining why things happen has aroused suspicion in philosophers. “Misaki,” reads one. And it has also raised suspicion in scientists themselves. “Viso: No Name Boys,” reads a second. Such distrust is reasonably common within strong empiricist views. “Miguel War City,” a third. Empiricists have seen science, most fundamentally, as a system of rules for predicting experience. With no street signs to help and our map on too large a scale, it is impossible to know where we are. When explanation is put forward as an extra goal for science. “Paris 2000,” reads a new shop’s sign. Scientific empiricists get nervous.

“Mickey,” reads another shop, selling tobacco. There is a complicated relationship. “Tutto Chicco,” a third, selling children’s clothes. Between this problem of explanation and the problem of analyzing confirmation and evidence. We have skirted a square with a modest monument “To the Dead of the Great War.” The hope has often been to treat these problems separately. We are heading toward a more important square, a pink building rising behind it, on whose front a sign reads, “Mercado do Livramento.” Understanding evidence is problem 1. This section of town is both old and new. Understanding explanation is problem 2. Some buildings are boarded up, others have just been built. Here we assume that we have already chosen our scientific theories. We continue on down a broad boulevard. At least for now. Past a little plaza with a name, past a park without one. The street, like most in Setúbal, has no sign.

We want to work out how our theories provide explanations. We have reached an expanse of cobblestoned sidewalks. In principle, we can make such a distinction. At cafés, tables and chairs have been set out in the sun. But there is a close connection between the issues. Over a charcoal fire a woman is grilling fish. The solution to problem 2 may affect how we solve problem 1. At last we reach a large rond point but again are at a loss to identify it. Theories are often preferred by scientists, because they seem to yield good explanations of puzzling phenomena. A traffic sign directs one to “Palmela,” to “Alcácer,” to “Lisboa.” In Chapter 3 explanatory inference was defined as inference from data. A police car stops before zebra stripes to let author cross over them, he with his tape recorder held before his mouth. To a hypothesis that would explain the data. We skirt much older buildings roofed in tiles.

This seems to be more prevalent in science than the philosophical idea of inductive inference. Their windows are small. (I. e., inference from particular cases to generalizations.) Lines for laundry have been strung from poles attached to their balconies. This suggests that there is a close relation between the problem of analyzing “explanation” and the problem of analyzing “evidence.” At “Mercearia Americo,” potatoes, piled in bins, seem to have been sorted by color: yellow, rose, brown. There is a large literature on explanation. Author steps to the front of a bar, planning to enter it. But these issues will get a whirlwind treatment here. Its door is open, music issuing from within. One reason is that I think the philosophy of science. He is told, however, that the place is closed. Has approached the problem of explanation in a mistaken way. At the risk of getting lost, author turns in again toward the old town.

Empiricist philosophers, I said above, have sometimes been distrustful of the idea that science explains things. Ancient two-story houses, with dormered windows representing a third story, sit jowl by jowl. Logical positivism is an example. All the houses are decorated in complicated Moorish tiles. The idea of explanation was sometimes associated by the positivists with the idea of achieving deep metaphysical insight into the world. We make a U-turn into a street whose stone dwellings have been painted a rosy brown, a rich cream, a Utrillo yellow, a light gray and a light turquoise. An idea that they would have nothing to do with. Most are flaked and peeled. But the logical positivists and logical empiricists did make peace with the idea that science explains. We come to Restaurante Vasco da Gama, a man outside in a gray/black/light gray striped sweater, smoking a cigarette as he flips a fish on a grill.

They did this by construing “explanation” in a low-key way that fitted into their empiricist picture. Cobblestone sidewalks and cobblestone streets are made of the same small size stones. This was the dominant philosophical theory about scientific explanation for a good part of the 20th century. We turn into a large plaza, in which the distinctively small cobblestones continue underfoot. The view is now dead, but its rise and fall are instructive. Five older men are talking at once, seated in green 7-Up chairs. The covering law theory of explanation was first developed in detail by Carl Hempel and Paul Oppenheim. “Os Piratas” reads a graffito at the corner of the square. In a paper (1948) that became a centerpiece of logical empiricist philosophy. We move continuously now from one small plaza to the next. A younger crowd is seated in yellow chairs before a sign reading “Snack Comi Cala.”

Let us begin with some terminology. Next door to it is “Café Arco-Iris,” not a single customer at its red tables and chairs. In talking about how explanation works. Three women in their early 30s are conversing before the open front door of a Mitsubishi agency showing off-road vehicles. The explanandum is whatever is being explained. The two women have identical, dyed, shoulder-length red hair and are both wearing leather jackets and tight black pants. The explanans is the thing that is doing the explaining. We reach an alleyway whose gray walls, rising to brown and pink, have been gouged by trucks and other vehicles. If we ask “why X?” then X is the explanandum. In our meandering we mindlessly exit the old part of town for a modern scene. If we answer “because Y,” then Y is the explanans. We read signs over the sidewalk for “Esso Lubri-Centro,” “Rent-a-Car,” “Ford Setu-Auto” and “Alucar.”

The basic ideas of the covering law theory are simple. Author admires a building in olive and pink, an orange tree before it. Most fundamentally, to explain something is to show how to derive it in a logical argument. We pass a Chinese restaurant with double golden-dragon columns against a red background. The explanandum will be the conclusion of the argument; the premises are the explanans. Its red outer doors have been opened to reveal carved mahogany inner doors with glass panels. A good explanation must first of all be a persuasive logical argument, but, in addition, the premises must contain at least one statement of a valid law of nature. Among the blue tiles set against a yellow background, on an ancient building, one depicts a lutanist, another, a violinist, both angelic in their poses. The law must make a real contribution to the argument; it cannot be something merely tacked on.

At the lower reaches of the building stylized graffiti have been carefully traced in white on black (“Frente”), in black on white (“Todos”), in white on black (“Diferentes”). Some explanations (both in science and in everyday life) are of particular events, whereas others are directed at general phenomena or regularities. Beneath these three words reads a slogan (“Todos Igual”), beneath them all a unifying rubric (“Anti-Racista”). For example, we might try to explain the particular fact that the U.S. stock market crashed in 1929 in terms of economic laws operating against the background conditions of the day. We circle back to the obelisk commemorating World War I soldiers. And we can also explain patterns. “Classic” reads the name of an auto showroom, referring to a red Mazda. Newton is sometimes seen as explaining Kepler’s laws of planetary motion in terms of the more basic laws of mechanics.

New graffiti: In combination with assumptions about the layout of the solar system. “No Gods, No Masters, Fuck Religion,” reads one; “Witches Rule,” another. In both cases, the covering law theory sees these explanations as expressed in terms of arguments from premises to conclusions. Two kids of fourteen have rested their skateboards on marble slabs set atop the circular masonry at the base of a Crucifix surmounting a column. Some of the arguments that express explanations will be deductively valid. As one kid talks on his cell phone, the other, in a Calvin Klein sweatshirt, flips his skateboard upright, then plants both his feet on it. But this is not required in all cases. Author crosses the plaza diagonally, down a ramp past a graffito reading “Follow the Leaders.” The covering law theory was intended to allow that some good explanations could be expressed as non-deductive arguments (in the broad sense).

We exit into a much smaller space. 13.3 Causation, Unification, and More. Before what appear to be two churches, side by side, one painted pink, white and blue, the other white, we continue on down to “Rua Balneário Dr. Paula Borba.” Did the dinosaurs become extinct 65 million years ago? This street has been swept clean. Here again, our request for an explanation seems to amount to a request for information about what caused the extinction. It is almost graffiti-less. Although that conclusion seems compelling. Till we reach the end of the alley. It has not been universally accepted. Where an ancient inscription reads: And it raises many further problems. “Merda,” the final “a” circled. At this point the biggest question is, What is causation? It leads us to two facing apartment towers, four stories tall, between which stands a third residential block. The idea of causation is extremely controversial in philosophy.

Rather than return at once to his original destination, author instead wanders among high rise housing units and a large space defined by arches. For many philosophers, causation is a suspicious metaphysical concept that we do best to avoid when trying to understand science. Apparently made of concrete, but perhaps the remnants of some older construction, say an arena. The suspicion is, again, common within the empiricist tradition. From this vantage point. It derives from the work of Hume. We survey a large field. The suspicion is directed especially at the idea of causation as a sort of hidden connection between things. Overgrown with high grass, beyond which lies another housing project. Unobservable but essential to the operation of the universe. We skirt a school, where kids, having just been released, are roughhousing in the courtyard. Empiricists try to understand things without assuming hidden connections.

At the entrance to a long white building a man, his reading glasses on a chain about his neck, steps through the portal accompanied by a much younger woman. The rise of scientific realism in the latter part of the 20th century led to some easing of this anxiety. A black woman of 30 steps back into the establishment. But many philosophers would be pleased to see an adequate account of science that did not get entangled with issues of causation. Author glances in through its portal to find a very large restaurant, rather informal, designed perhaps for the working class residents of these housing projects. Despite this unease, toward the end of the 20th century, the main proposal about explanation being discussed was the idea that explaining something is giving information about how it was caused. A young man stops his red car at curbside, rolls down the window, and comments on author’s commentary.

Sophisticated analyses were developed that sought by using probability theory to clarify this basic idea. Author turns to study a professional graffito: “Tróia è de todos / as.” It might seem initially that this view of explanation is most directly applied to those of particular events (such as the extinction of the dinosaurs). Beneath this message is depicted an abstract horizon of high-rise buildings. But it can also be applied to the explanation of patterns. Beneath which cut-out figures of children, beneath them another graffito: “Why does in-breeding produce an increase in birth defects? “Não ao turismo de luxo” (“No,” perhaps to a government program encouraging the development of tourism). The explanation will describe a general kind of causal process involved in producing the phenomenon: A red communist star adorns the work. An increased chance that two copies of a recessive gene will be brought together.

♥

Pre-dawn arrival (1/2000), Doca dos Pescadores, Setúbal, in hopes that the sardine boats have not yet come in (they already have, it turns out). The Portuguese News Online (1/2010). The sky is crisp, the moon moving into its crescent phase. Lowly Sardine Gains Respect with “Certificate of Quality.” Aphrodite (Venus) high, like a gorgeous navel in that sky. Portugal’s acclaimed sardine, after being awarded the certification of “Sustainable Product of Quality.” The Tasca do Rato is closed. By the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC). As is Restaurante Gastronómico. During “International Year for Biodiversity.” A woman is already hanging the bottoms of a set of long underwear from a balcony. Portugal’s acclaimed sardine is now being heralded as a promising enrichment to the fishing industry. A policeman, or perhaps customs official, checks out author. Which could bring fresh opportunities to the national sector.

The Café o Plano is open and noisy within. António Serrano. Three fishermen enter. The Portuguese Minister of Fisheries. Talking a lot about fish, so far as author can understand them. Last week declared. Before long the three are joined by half a dozen more fishermen. That the certification of the sardine. All wearing stocking caps or baseball caps. Would bring added value to the fishing industry. Cold but bluff, stamping their feet, swatting each other on the back, hugging one another, they must have just come in from the sea. “A sardine with a certificate,” said Serrano, “will see its chain value greatly improved.” Many of them are toothless. “And the market will also notice a difference.” At the mouth of the port sits a boat bearing the name “Helena Sandra,” next to it, on her bow, a red five-point star. “The consumer is privileged, and fishermen, with a quality product, have the possibility of increasing their income.”

Painted blue, white and red, she is out of the water, waiting to be worked on. Minister Serrano believes that Portugal’s sardine is “an example to be followed in many areas.” Small skiffs, very small (with outboard motors; one with oars), are idling in the harbor, having finished their day’s work. The “Sustainable Product of Quality” certification given to the sardine by the MSC acknowledges concerns in guaranteeing the sustainability of resources. With the lightening blue of the sky the water of the bay has also turned light blue. And the efforts made to preserve marine species, particularly the compliance with capture limits imposed on the industry. With no signs of any more boats entering the harbor, author heads for the outermost quay to view the sea. Portugal’s marine fish species number in the thousands and include the sardine (Sardina pilchardus), tuna and Atlantic Mackerel (from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia).

A gray stretch of water at the horizon is now surmounted by a rose-gray stretch of sky. Marine bioluminescence is very well represented (in different colors, spectra and forms). Then a rose band, then a very light blue. With interesting phenomena like glowing plankton. “Resources are limited and must be managed in a very efficient and sustainable manner,” the minister emphasized. At last a fishing boat appears, but it seems to be heading out to sea. It is also possible in Portugal to observe the upwelling phenomena, especially on the west coast, which makes the sea extremely rich in nutrients. Off in the distance are the buildings of Tróia, a suburb of Setúbal. Sardines captured off the Portuguese coast are the first EU species to be awarded the MSC’s “Blue Label” certificate of sustainability and quality. Portugal’s marine waters are among the world’s richest in biodiversity. Its high rise buildings visible.

It was the 60th species of fish in the world to receive the certification despite 160 certification requests. On the wharf three men are wrestling a long boat over the cobblestones. Altogether the MSC-certified fish represent 6,500 tons of captured fish. Beneath a ring of harbor lights. Or ten per cent of the world’s global production. A siren goes off, as smaller boats leave and enter the harbor, the shrill sound agitating a flock of white gulls, which swirl about in all directions. Certification of the Portuguese sardine was requested by the National Association for Fisheries and the National Association for Fish Conservation Industries. We observe nets being deposited at harbor side, then covered with tarpaulin. The MSC is a non-profit international organization responsible for the only fish-certification program in the world. We have now reached the end of the quay, where two white poles indicate the entrance into the harbor.

“This certification,” Rupert Howes, executive director of the MSC, explained, “means that the fishing of sardines has been submitted to rigorous evaluation by scientists who validated compliance with the certification’s main principles:” The little boats continue to leave the harbor, perhaps the boats of those fishermen who, having deposited their catch, are returning home. “Sustainability of resources, effective management and the quality of the fish.” As author peers through a slight haze, however, the little boats seem to be heading out toward a lighthouse, at one end of the crescent of the bay. “There are more and more parties interested in certifying their products as the certification makes them appealing to new markets and incurs bigger financial earnings,” he added. On closer inspection it appears that some of them are heading toward Tróia, on the opposite side of the bay from a crane, two smokestacks of a docked ship.

Portugal’s latest accolade acknowledges more than a hundred fishing vessels and eleven of the country’s fourteen food preparation industries. Now a slightly larger skiff makes its way in toward the mouth of the harbor, one man standing, another sitting in her bow. Sardines represent 40 per cent of all fish captured by Portuguese vessels. The waters here have a greenish cast. And weighed in at 60,000 tons in 2008. As author is completing his perambulation of quay and harbor, a red fishing boat, the “Unidos,” passes him, a single light bulb illuminating its cabin. A third of the catch is channeled into the food preparation industry. In a black and blue parka with red shoulders and back another fisherman is loosening his lines. Which exports more than 50 per cent of its products. Having docked near the exit portal. One of the most famous arguably being sardine pâté. Its surface in white-overpainted, corroded ironwork.

Known as the “Cathedral of the Sardine,” Portimão, a city in the Argave, hosted its first “Sardine Festival” in 1985, a summer event which over the past few years has seen tens of thousands of people flocking to it. High on a wooded hill are the ramparts of an ancient castle. For a chance to taste the traditional delicacy. This sprawling fishing port and canning center (The Lonely Planet Guide) hogs the western bank of the Rio de Arade three kilometers inland from Praia da Rocha. The sky lightens, illuminating a handsome white house, expansive, serene, emblematic of an earlier era. Hannibal himself is said to have set foot in Portimão, whose past sounds more glorious than its present. A boat being worked on bears the name “Artifici/Profano.” The sardines are typically served with boiled potatoes, salad and lots of wine. It was called Portos Magnos by the Romans and fought over by Moors and Christians.

♥

Lisbon, January 29, 2000. Legend has it that Lisbon was founded by Ulysses. We exit the Metro into the Praça dos Restauradores. But the Phoenicians were probably the first to settle here. It is a late Saturday morning. (The Lonely Planet Guide.) Two teenagers, a boy and a girl, are standing in front of a bar called O Pirata, where middle-aged types slowly sip their glasses of wine. Three thousand years ago. The kids dressed in Chicago Bulls warm-up suits, white jackets, full-length white pants. Attracted by the fine harbor and strategic hill, they called the city Alis Uppo (Delightful Shore). Road Runner Records has huge displays in its window. Others soon recognized its delightful qualities. For Sepultura, Coal Chamber, Misfit, Machine Head. Greeks displaced the Phoenicians and were booted out by Carthaginians. We pause at a large modern bookstore that says it has branches in Amsterdam and Seville.

These shops are on the ground floor of a massive granite building, whose gray upper reaches are ornamented with pink-painted columns leading to a frieze beneath a large square-lettered metal sign reading “EDEN TEATRO.” Julius Caesar raised the city’s rank and changed its name to Felicitas Julia. Author enters the music store to examine “Novidades,” new releases, almost exclusively American. Making it the most important in Lusitania. To one side of Eden, in the same building, sits the “Orion Hotel.” After the Romans, and various northern tribes, the Moors arrived in 714 from North Africa. Eight-year-olds, finished with their half day of school, are trekking up a steep street into the square, the boys wearing their scout uniforms; their teacher, wearing mountain boots and white Alpine socks, carries a walking stick. They fortified Lissabona and fended off the Christians for the next 400 years.

The skies are crystal clear, sun catching the wings of birds flying overhead, high above the square. Since the fall of Rome there had been no empire based in Europe that extended outside the continent. Up an alley are the tracks for Lisbon’s trolley cars, famous for negotiating this severe incline. The situation changes abruptly in the 16th century, when Spain and Portugal become the pioneers in a new era of colonization. We pass the Cafeteria Palladium. In their great voyages of discovery. An Egyptian image advertises the opera “Nefertiti,” the face of the Portuguese star enlarged on the poster. During the 15th century. We arrive at a Rover showroom, a dark green model in its window. The Portuguese developed ocean-going skills. EDEN Tours is showing video scenes of it attractions on TV monitors. Which were copied by their Spanish neighbors. In this long plaza we turn right to continue our clockwise motion through it.

Spain’s internal conflicts of the past few centuries were resolved with the union of Castile and Aragon. Facing into the sun, we momentarily leave the plaza. Then, in 1492, the conquest of Granada. We skirt an outdoor café, adorned with pink table cloths and white grillwork cast iron chairs. Two voyages in the 1490s laid the foundations for the future empires. It is 15 degrees centigrade in Lisbon, the warmest of any European city today. Christopher Columbus, sailing west for Spain, stumbled upon America in 1492. Down an alley, on a pink stuccoed building with a beautiful white entranceway, a neon sign reads “Solmar,” a sunburst, also in neon, behind it, three wavy lines indicating water below it. Vasco da Gama, adventuring south and east for Portugal, reached India in 1498. We examine pink, blue and white flowers attached to pussy willow branches in a florist’s shop window, then roses, jonquils and other blossoms.

The profitable trade in eastern spices was cornered by the Portuguese in the 16th century. We scrutinize a globe made up of tiny photographs of people from early childhood to old age. To the detriment of Venice, which had had a monopoly on these valuable commodities. “Nazis Go Home,” reads a graffito. Until then transported overland through India and Arabia. A tailor is selling traditional men’s clothing: Later, across the Mediterranean by the Venetians. Suits in gray and blue pinstripes; an olive shirt; an expensive pair of tan slacks. For distribution in Western Europe. We pass a sales booth for tickets, theatrical, operatic, cinematic. By establishing the sea route round the cape, Portugal could undercut the Venetian trade, with its profusion of middlemen. As we complete our circuit of the plaza we reach the Hotel Avenida Palace, across from which a liquor store is showing expensive varieties of Port and Madeira wines.

The new route was firmly established for Portugal by Alfonso de Albuquerque, who took up his duties as the Portuguese viceroy of India in 1508. Ahead on the right rises an attractive, if not especially distinguished, facade that evokes the glories of the Portuguese empire, though it was doubtless constructed after 1755. The early explorers up the east Africa coast had left Portugal with bases in Mozambique and Zanzibar. This street communicates with the Praça do Commercios. Albuquerque in 1514 extended a secure route eastwards by capturing and fortifying Hormuz. A young man is hand-lettering an old-style all-capitals sign on a pilaster, the first stage of which rises half way up the ground floor. At the mouth of the Persian Gulf. He is working on the “A” in “PISTOLA.” Earlier, Goa (1510) on the west coast of India (where he massacred the entire Muslim population) and Malacca (1511) on a channel to the East.

In the next plaza pigeons are strolling the cobblestones with a proprietary air. The island of Bombay was ceded to the Portuguese in 1534. A group of black Africans has congregated. The early presence in Sri Lanka was steadily increased. The far side of the square is sunlit. During this century. At one end of it rises a hill, revealing ornate older buildings, their stucco in various stages of disrepair. Then, in 1557, Portuguese merchants established a colony. Banks (quite naturally) line the other side of the plaza. On the island of Macao. Two women, one dressed all in black, the other in a metallic silver cape, are entering a fancy café called “Nicola.” Goa, from the start. Everywhere that one turns in search of a flatfooted equilibrium a steep street or alleyway intervenes. Functioned as the capital of Portuguese India. We chose at last the Rua del Carmo, only to come upon gray scaffolding set up halfway out into the street.

In their bold exploration along the coasts of Africa. Farther up this narrow alley, right in the middle of it, looms a cast iron tower, atop it a platform, presumably for a funicular station. The Portuguese had had an underlying purpose: An early-model green truck, its vendor’s window open on one side, is purveying for the passerby classical folk music. To sail round the continent to the spice markets of the East. By playing the mellow strains of a lutanist, who is also heard accompanying sentimental vocalists. But in the process they developed a trading interest. As we mount higher we encounter higher and higher fashion. And a lasting presence in Africa itself. Once past a fancy Italian shoe store, we turn into the Rua Barrett, skirting Zarra, a fashion outlet on one side, Mac, another, situated across the street. (An on-line history of the Portuguese empire, “Portugal’s Eastern Trade,” “Portugal’s Empire,” “Portugal and Brazil,” etc.)

In Calçada do Sacramento we observe the leaking facade of an 18th century church. On the west coast of Africa Portugal’s interest was in the slave trade. Advertisements fill a deserted shop window next to it: Thereby resulting in Portuguese settlements in both Guinea and Angola. One ad is promoting the final volume in a trilogy by Luís Castro, Mur Ral Elo. On the east coast they were drawn to Mozambique and the Zambezi River by news of a chief. The whole trilogy, it would appear, goes by the title Moç Amor. The Munhumutapa, who had fabulous wealth in gold. Shops now become smaller and more individuated: a women’s shoe store, a men’s shirt store, a bookstore for discriminating readers. We are passing another 18th century ecclesiastical structure, as author looks for the Rua Serpa Pinto. Accordingly, they established a settlement at Tete, some 260 miles from the sea. Glancing down, we glimpse the Atlantic.

All this we might say was adumbrated in, and celebrated by, the epic of Portuguese discoveries. The redolent surface of the sea is banded in light blue, dark blue and turquoise. By Vasco da Gama. We continue on to Baixa-Chiado, where cafés have established semi-permanent territories, replete with serving stands and barriers. Known as Os Lusíadas (“The Lusiads,” about the People of Lusus). Capping a rise, we begin to descend again, as a trolley car heads upwards. A people predestined by the Fates to accomplish great deeds. “Competência y Responsabilidade” reads a slogan for Bayer Aspirin. The “new kingdom that they exalted so much.” We pass yet another ecclesiastical building, more baroque than the earlier two. Was the inspiration for Camoens. We have reached the Rua da Misericórdia. To complete his great Portuguese epic. The Praça Luís Camões is undergoing reconstruction.

The poem begins with the poet paying homage to Virgil and Homer. A handsome square with institutional blocks of apartments lining either side. The story portrays the gods of Greece watching over the voyage of Vasco da Gama. A sign informs us that a subterranean parking garage is planned at its center. Just as the gods had divided loyalties during the voyages of Odysseus and Aeneas. One of the blocks is deserted, its windows bricked up, pigeons elsewhere roosting in spaces formed by broken panes of glass. So here Venus, who favors the Portuguese, is opposed by Bacchus. Two hands, one white with a black streak running up from the wrist, the other black with a white streak, have been carefully executed on a metallic door shade pulled down. Who is here associated with the east and resents the encroachment on his lands. At the Rua das Flores we look out to and down upon the sea.

We join Vasco da Gama in medias res (Canto I). We sight boats on the water and a crane loading a ship. He and his men have already rounded the Cape of Good Hope. The street descends in an irregular way, sunlight stronger on the buildings below than those above. At the urging of Bacchus, disguised as a Moor, the local Muslims plot to attack the explorer and his crew. “Timor Livre! Já!!” reads a graffito on a corrugated metal wall surrounding an excavation. Two scouts sent by da Gama. An olive bus pulls alongside author. Are fooled, by a fake altar created by Bacchus, into thinking that Christians are among the Muslims (Canto II). Its passengers constitute, so it would seem, a military band. Thus are the explorers lured into an ambush. At Rua do Alicem we descend once more, the sea now within our reach. But they survive with the aid of Venus. Brasserie à l’entrecôte has its menu in a glass box.

Venus pleads with her father, Jove, who predicts great fortunes for the Portuguese in the East. A studious man of liberal persuasion, wearing a pea jacket, a patterned sweater underneath, a work shirt and Levis, walks up the hill studying its ambiance through his silver-rimmed glasses. After an appeal by the poet to Calliope (Canto III). Suddenly author arrives at the edge of a square. The Greek muse of epic poetry. Where the sun is shining through the irises, they in full blossom. Vasco da Gama begins to narrate the History of Portugal. In front of a statue of Eça de Queiroz. He starts by referring to the situation of Portugal in Europe. A fin-de-siècle nude spreading her arms and gazing adoringly at a fully-clad gentleman. And the legendary story of Lusus and Viriathus. Has been covered with graffiti. This is followed by: A grove of palm trees bows itself against a background of airy pine trees.

Passages on the meaning of Portuguese nationality. Idling in the square is a fire truck. Then on the warrior deeds of the 1st Dynasty kings. Before which stand two women, both wearing red caps, one in a blue fireman’s suit and a red belt, the other in a black sweater, a red stripe across it. From D. Afonso Henriques to D. Fernando. Because her clothes are too warm for her, the second, more portly of the two, removes her sweater, as two slim girls in their early 20s, one in a black sweater, one in a blue, descend the canted plaza. Episodes that stand out include Egas Moniz and the Battle of Ourique. We are standing within the pleasant space of the Largo do Barão de Quintela. During Afonso Henrique’s reign. Fábrica Sant’Anna is showing exquisite ceramics: Formosíssima Maria in the Battle of Salado. 18th century vases, lamps made of vases, ceramic baskets. And Inês de Castro during D. Afonso IV’s reign.

The traffic in the square has been halted by the descent of the fire truck into it, giving author a chance to study its graffiti. Vasco da Gama continues the narrative of the history of Portugal by recounting the story of the 2nd Dynasty (Canto IV). On a pink building reads the single word “Obey,” the “e” elongated to twice the width of the other letters. From the Revolution of 1382-1385. “Shamo,” reads another in pink, barely legible against the pink wall. Till the reign of D. Manuel I, when the Armada of Vasco da Gama sets sail for India. A man with a pink nose (painted pink, it would appear), wearing broad black-rimmed glasses and a black beret, mounts the street past author, giving him a European once-over. It focuses on the Battle of Aljubarrota and is followed by the expansion into Africa under D. João II. We have reached a point at which the street diverges from what rises above it.

Following this momentous event, the poem narrates the journey to India. An empty space on the left is followed by an embankment. Under D. Manuel. Followed in turn by houses with five, six, eight stories. To whom the rivers Indus and Ganges appeared in dreams that foretold the future glories of the Orient. Their foundations in turn bear the signs of other, earlier houses that had stood upon them: stairways, the outlines of rooms, bricks showing through the stucco. This canto ends with the sailing of the Armada. Presently we reach the Rua do Ataíde. The sailors in which are surprised by the prophetically pessimistic words of an old man. Quickly it descends, only with equal alacrity to ascend into a stretch bordered with black and gray cars, all the way up to an arch through which one views a sunlit, rose building. “Silver Kids,” reads a red graffito. Velho do Restelo, was on the beach among the crowd.

Midway down the street, next to green, framed, wooden windows, a huge chute for the convenient removal of refuse from a site of remodeling six stories above is formed by large plastic cans, set into one another and held together by a chain. Next the story takes up the King of Melinde (Canto V). The sunlit side of the street is lined with advertising posters for dramatic performances, which repeat themselves in every other rectangular frame. Describing the journey of the Armada from Lisbon to Melinde. “Take me down,” reads a graffito. During the voyage, the sailors see the Southern Cross, St. Elmo’s Fire, and face a variety of dangers and obstacles such as the hostility of natives in the episode of Fernão Veloso, the fury of the Giant Adamastor. The descending street issues into a plaza, which itself slopes downward. And the disease and death that is caused by scurvy. “Happy Birthday David,” reads another.

Canto V ends with the poet’s censure of those contemporaries who despise poetry. We have reached an overpass, from which we look down two stories onto a street earlier filled with trolleys, now with buses. After da Gama’s narrative, the Armada (Canto VI) sails from Melinde. Hanging out to dry is a line of laundry. Guided by a pilot to teach them the way to Calicut. Above the deep canyon of the descending street, which diminishes in perfect perspective. Bacchus, seeing that the Portuguese are about to arrive in India, asks for help from Neptune. The tower of another ecclesiastical building catches the sun. Who convenes a Council of the Maritime Gods. “CasiaJunior” has a blue and yellow awning. Who support Bacchus and unleash powerful winds to sink the Armada. Across the way, on the wall of a run-down building, graffiti in magenta, coral and purple fill otherwise unused archways.

Seeing the near destruction of his caravels, da Gama prays to his own God, but it is Venus who helps the Portuguese. We have descended almost to the sea and are about to enter into a plaza at whose center stands an heroic figure in bronze, gazing outward, his sword beside him. By sending the Nymphs to seduce the winds and calm them down. The monument is dated Lisbõa XXIV de Julho de MDCCCXXXIII. After the storm. Author stops in the plaza for a shoeshine from a man who says that life is horrible. The Armada sights Calicut. A kindly café owner helps him negotiate a payphone, but unsuccessfully. And da Gama gives thanks to God. Author’s confirmation of his ongoing flight will have to wait till he returns to his hotel. The canto ends with the poet speculating on the value of the fame and glory attainable through great deeds. Crossing the square, he continues on down to the water’s edge.

After condemning other European nations (Canto VII). We are passing a train station. Who in his opinion fail to live up to Christian ideals. A circled “A” indicates Anarchy. The poet tells of the Portuguese fleet reaching the Indian city of Calicut. “Podér Ção,” reads an inscription. A Muslim named Monsayeed greets the fleet and tells the explorers about the lands that they have reached. Propping his arm against a lamppost, author drops his recorder onto the cobblestones and loses a spring. King Samorin summons them. We reach a quay full of old buildings and new restaurants. He receives them well. An orange ferry is pulling out from dock, its passengers on deck for the brief passage across the harbor. The Catual, an official of the king, visits the Portuguese ships. Though the sun is bright, a sign warns of “Danger.” And confirms what Monsayeed has said. Waves arrive on shore from the ferry’s departure.

The Catual views paintings depicting Portuguese history (Canto VIII). Atop a hill at the end of the Vasco da Gama Bridge stands a truncated obelisk. Bacchus appears in a vision to a Muslim priest in Samorin’s court. It bears the figure of Christ, his arms extended. The priest spreads warnings among the court, prompting King Samorin to confront Vasco da Gama. From there onward the harbor and coastline grow increasingly industrialized. And to confirm what Monsayeed had said. A shipyard’s sign reads “Lis Nave.” Da Gama insists that the Portuguese are traders, not buccaneers. Another ferry, its side sun struck, crosses the harbor in this direction. The king demands proof from da Gama’s ships, but the Catual refuses to lend him a boat for the purpose. We cautiously avoid cars turning in our path. Held prisoner, da Gama is only freed after he agrees to bring the goods on his ships to shore for sale.

A man in white hair and a white mustache leans on a kiosk, drinking a beer. (Canto IX.) This part of the square is designated “Jardim Roque Gameiro,” after a water-colorist, it appears. The Muslims plot to detain the Portuguese. The garden in question has been almost totally denuded of grass. Until the annual trading fleet from Mecca can arrive to attack them. Across from it, in a narrow rondel bordered with two-inch high iron spikes, stands a piece of sculpture, arduous and extreme. But Monsayeed informs da Gama of the conspiracy. It bears a late 19th/early 20th century inscription. And his ships escape from Calicut. A sailor in an old-fashioned nautical hat tugs at a rudder. To reward the explorers for their efforts. As he looks down toward the harbor. Venus prepares an island for them to rest on. Uncertain as to what the result of his struggle will be. And has Cupid inspire the Nereids with desire for them.

We pass up the avenue that separates the two halves of the square. During a sumptuous feast on the Isle of Love (Canto X). We are passed by another double-trolley. Tethys, who is now the lover of da Gama. Actually with a third section in its middle. Prophesies the future of Portuguese exploration and conquest. From which rise armatures bearing electric lines. She tells of Duarte Pacheco Pereira’s defense of Cochim. “Coca-Cola,” in enormous letters adorns its side from front to back. The Battle of Diu (1590), fought against Gujarati-Egyptian fleets. Out of the square author proceeds. The deeds of da Cunha and de Sampaio. Up this relatively modern avenue, which, according to the map, changes its name section by section. And the battles fought by de Sousa and de Castro. The temperature has risen to 18 degrees centigrade. Tethys then guides Vasco da Gama to a summit and in a vision reveals to him:

It is 3:54 pm. How the Ptolemaic universe operates. We have passed the last stop on the Metro line, Caisdosodré, and continue west. The tour continues. As we follow the sidewalk out of Old Lisbon, new public transportation platforms line it at not-too-great intervals. With glimpses of the lands of Africa and Asia. Atop the clunky if rigorously girded structure of one sits a train, its cars predominantly silver but green around the windows. The legend of the martyrdom. It is neither arriving nor departing. Of St. Thomas in India. As we walk past its last car, we can see across to other trains all in a similar condition. At this point. The track here has been recently laid on wooden ties. Finally, Tethys relates the voyage of Magellan. Gradually we reach the train yard’s outbuildings. The epic concludes with more advice to young King Sebastião. And look out over the water again to the Christ with outstretched arms.

♥

For an account of a probabilistic universe of multiple possibilities author draws upon the work of Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow, first from their Scientific American article, “The (Elusive) Theory of Everything,” then from their book, The Grand Design:

The way physics has been going, realism is becoming difficult to defend. Author sets out for return on foot to Praça de Espanha. In classical physics — the physics of Newton that so accurately describes our everyday experience — the interpretation of terms such as object and position is in harmony with our commonsense, “realistic” understanding of those concepts. A sign directs us toward Biblioteca Pública. As measuring devices, however, we are crude instruments. We pause at “Kids Dream, 0-16,” whose window shows pictures of fruit juice and tea, “T-3.” Physicists have found that everyday objects and the light we see them by are made from objects. We confront a new building, the word “Ultimos” on it.” Such as electrons and photons. This as yet uninhabited structure is quite attractive, its design in blue-gray concrete, corrugated silver, curvilinear white. That we do not perceive directly.

Down the sunlit street, at a table set up beside a café, a four-handed game of cards is in progress. The reality of quantum theory is a radical departure from that of classical physics. A dozen men are involved, the four players plus eight other participants. In the framework of quantum theory, particles have neither definite positions nor definite velocities, unless an observer measures those quantities. All are in their early 60s. In some cases, individual objects do not even have an independent existence. Half are smoking cigarettes. But rather exist only as part of an ensemble of many. We pass a shop whose only sign has been embroidered in the manner of a sampler. Quantum physics also has important implications for our concept of the past. “RetrosariaMadrePerola,” all one word, its window is displaying blue and pink baby clothes: booties, knit gloves, tiny crocheted handbags.

In classical physics the past exists as a definite series of events. “Fechado,” reads a purple-on-white sign, also embroidered. But according to quantum physics the past, like the future, is indefinite. With some relief we return to the mix of old and new. It exists only as a spectrum of possibilities. A woman in orange pants and silver slippers, long black overcoat, stands by a waist high wall, her purse and her wallet open atop it, as she talks into a cell phone in an animated way. Even the universe as a whole has no single past or history. A black Ford is parked in an alleyway. So quantum physics implies a different reality than that of classical physics. Its driver’s side door, having been broadsided. Even though the latter is consistent with our intuition. Is now held together with plastic tape. And still serves us well when we design things such as buildings and bridges. “Cult” reads a single-word graffito.

These examples bring us to a conclusion that provides a framework within which to interpret modern science. We have reached “Beau Séjour,” founded in 1859. In our view, there is no theory-independent concept of reality. Its buildings are occluded by a variety of deciduous trees in full foliage. Instead we adopt what we call “model-dependent realism”: We pass a little park whose playground is fenced to 20 feet with green chain-link. The idea that a physical theory is a model. In it a father wearing a dark green shirt kicks a light green ball to his seven-year-old son. And a set of rules that connects the elements of the model to observations. We look into a barber shop where a balding barber reads the paper as he waits for customers. According to model-dependent realism, it is pointless to ask whether a model is real, only whether it agrees with observation. We reach a shop for Mobiliário.

According to quantum physics, no matter how much information we obtain or how powerful our computing abilities. Within its window a sailor painted brown has rescued a maiden with long tresses and seated her on his shoulder. The outcomes of physical processes cannot be predicted with certainty. “Abaixo o fascismo! 1974-1998!” reads a graffito beneath a block of rather dreary apartments. Because they are not determined with certainty. We pause before a shop bearing the name “Pastelinho de Benfica.” Instead, given the initial state of a system, nature determines its future state. Out of which issues the delicious aroma of pastries. Through a process that is fundamentally uncertain. In its window is a cake bearing atop it a pair of dark chocolate shoes. In other words, nature does not dictate the outcome of any process or experiment. With long white strips added in plastic, laced up and tied.

Rather, it allows a number of different eventualities. At its corner reads a graffito in gold: Each with a certain likelihood of being realized. “Sim Verdade Tu Eis Perdedor.” It is, to paraphrase Einstein, as if God throws the dice before deciding the result of every physical process. We continue on up the street, which is growing increasingly irregular. That idea bothered Einstein. Along one of its walls reads a large graffito, “Morte Aos Ladrões!!!” And so, even though he was one of the founders of quantum physics. A clock reads 3:38, but its second hand is not moving. He later became critical of it. Above its face reads another sign to which it is attached: “Relogios Cosmos.” Quantum physics might seem to undermine the idea that nature is governed by laws. Within the second sign is a clock reading 9 minutes to 2:00. But that is not the case. It is merely a painted component of the second sign.

Instead it leads us to accept a new form of determinism: The clear sky is beginning to fill with a skein of light clouds. Given the state of a system at some time, the laws of nature determine the probabilities of various futures and pasts. Which introduce a mildness into the early afternoon sunlight. Rather than determining the future and past with certainty. As it strikes the dirty gray, dirty olive, dirty green and dirty pink buildings on the other side of the street. Though this is distasteful to some. “Sapataria Actual” reads the sign above a shoe store filled with hiking gear. Scientists must accept theories that agree with experiment. Its glass door has been broken and is being held together with plastic tape. Not with their own preconceived notions. Across the way is a graffito composed of homemade runes.

Probabilities in quantum theories reflect a fundamental randomness in nature. Above the ground floor a solitary man leans over the balcony to enjoy the sun (which has now broken through the clouds) and perhaps to escape from his family. The quantum model of nature encompasses principles that contradict. “Sharp Skins” reads a black graffito. Not only our everyday experience. In this block are two stores named “Supermercado,” on either side of a BancoMello. But our intuitive concept of reality. We pass a Chinese restaurant named “Shin O Fan Dian” (“Nova Europa”). Those who find these principles weird or difficult to believe are in good company. An illegible graffito in the punker style has been tagged in white on a gray slate building front. The company of great physicists, such as Einstein and even Feynman, whose description of quantum theory we will next present to the reader.