“Once you are with us, you will come back for more” (Hanoi ad). When I started writing Perl (Larry Wall), I’d actually been steeped in enough postmodernism to know that that’s what I wanted to do. “Perfume Pagoda” (another ad). Because you can’t actually do something postmodern. “New Style, 40 Hang Bac Street.” You can only do something cool. A red flag, a large yellow star at its center. Something that turns out to be postmodern. “Long (Dragon) Gallery.” Hmm. Do I really believe that? “Export—tous pays.” I dunno. “Fred Souvenir.” You may find this hard to believe. “Vietnam Railway.” But I didn’t actually set out to write a postmodern talk. “Et-Pumpkin.” I was just going to say how postmodern Perl is. “Prince 79 Hotel.” Anyway, thanks to you all for coming. “Prince” in green, “79” in red. I was hoping that the title of my talk. “Bamboo Hotel.” Would scare away. “Vietcombank ATM.” Anyone who shouldn’t be here. Its metallic, yellow face intaglioed into a wicker screen beside the hotel’s entrance.

We have reached the corner of Ta Hien Street. At “World Music CD Shop” a black saxophonist leans backwards in silhouette against a large pale yellow sun. “Golden Buffalo Travel.” In the act of writing author is offered a half-peeled orange that is sitting atop a basketful of unpeeled oranges. The Modern period. By a woman in conical straw hat who is balancing two baskets suspended by twine from her don ganh (shoulder pole). Is the period that refuses to die. A second woman offers you-tiao (oil fried bread sticks), both vendeuses smiling but both also disappointed that author is working, not relaxing as tourists should. He has started his day early: it’s not yet 7:00 o’clock. Today’s world is a rather odd mix of the Modern and the postmodern. On the sidewalk, at an intersection, a professional bicycle repairman scrapes at an inner tube preparatory to patching it. Oddly, this is not just because the Modern refuses to die. His customer’s bike laying on its side atop the oil-soaked paving stones. But also because the postmodern refuses to kill the Modern.

Hanoi seems to have all but relinquished its anti-American sentiment. But then the postmodern refuses to kill anything completely. Author’s reception thus far has been uniformly polite, often friendly. Deconstruction, you see, is simultaneously Modern and postmodern. We turn in the direction of the lake. Being both reductionistic and holistic. Café Sinh To Hoa Qua has just opened its tiny single room for business. Be that as it may. Holding her hands between her legs against the chill, seated on a small maroon plastic stool at its entrance. In religious terms. Is a pretty girl of 20, in pink sweater and elegant openwork leather shoes. Modernism may be viewed as a series of cults. From within the café’s darkened interior the tip of a lighted cig glows bright red as an almost invisible man drags on it. One way to define “postmodernism” is. A bead curtain swaying in the breeze. That it tries to escape from those cults. Along the curb are ranged plastic stools alternating maroon and baby blue. It’s a kind of deprogramming, if you will. Red crates of empty Coke bottles are stacked atop blue crates of empty Pepsi bottles, Heinekens atop Tiger Beer.

At Gia Ngu a street market is lazily opening. Before the French invasion. The street itself thereby rendered impassible by all but motorbikes. Earlier Viet Nam has a self-sufficient, agricultural economy. Cut cabbages, kale, onions, mint, more mysterious, unnamable produce. In which animal husbandry was not yet separated from growing. Cucumbers, carrots, lettuce, legumes. Handicrafts were not yet a specialized industry. Behind the stalls of produce are storefronts advertising ceramics, metal wares, fabrics. Many trades existed only when there were farm slacks. The prices of different agricultural products have been magic-markered in light blue on a whiteboard.

In 1884 the French completed their annexation of Viet Nam and began to impose their colonization. A boy steps up in black sandals, black shorts and a black-armed shirt, its white front reading in bold black letters:

A B C

D E F G H I

J K L M N O P

Q R S T U V

W X Y Z

Their policy was to turn Viet Nam into a market for France. Behind this scene crouch three older women leaning over their bowls of noodles, one with her chopsticks suspended in mid-air as she vociferates. They tried to make it entirely dependent upon the mother country. Meanwhile a beautiful younger woman lounges to one side, her bare foot dangling above a sandal deposited on the parterre, a street sign above her head reading “Pho Gia Ngu.” So that France could exploit cheap labor and other resources from its colony. As she eats her noodles. Meanwhile imposing an absurdly heavy system of taxation. A rose merchant in rose-patterned smock unbundles her flowers. Between 1897 and 1914.

Snipping the straws that bind together individual stalks. She carried out her first colonial exploitation policy. Now she removes the small damp pieces of newsprint in which the individual blossoms have been wrapped. Between 1919 and 1929 she implemented her second policy of exploitation. With her shears she removes unwanted leaves. These policies drained Viet Nam and caused resentment among the people. Next she stacks the pink roses on top of the red roses, offering author a sample of each, for sale. And brought about violent socio-economic changes. The petals outlined on her smock are salmon-colored, the leaves attached to them pale turquoise; the blouse beneath has a lacy collar.

New economic structures came into being: Next to her stall is the stall of an old man, his liver-spotted pate tufted in white. Industry. He is tending three varieties of eggs: Mining. Duck (in off-white). Transportation. Chicken (in beige). And foreign trade. Quail (spotted). Capitalists appeared in the agricultural sector. Above plastic basins of peanuts, beans and pancakes. I.e., plantations managed by French or indigenous landowners. Sit glass and plastic containers of condiments, all labeled in red, yellow and black. Accordingly, by the beginning of the 20th century Viet Nam no longer could boast a self-sufficient, agricultural economy but instead had separate, dependent industries and new social classes.

Unix is really simultaneously Modern and postmodern. Standing behind an empty case, a bright inner-illuminated sign above it, a man encourages author to describe a woman seated across the narrow passageway. Unix philosophy is supposed to be reductionistic and minimalistic. She is scraping at her black wok to keep roasting chestnuts from burning. But instead of being Modernistic, Unix is actually deconstructionistic. There follow stalls of chicken butchers. The saving grace of deconstructionism. Pork butchers. Is that it’s also reconstructionism. Calf and beef butchers. When you’ve broken everything down into bits, you have to put them all back together again.

Followed by stalls for fruit and for large-scale produce. On 2 September 1945. Followed by cooking oil and cooking utensils for sale. President Ho Chi Minh. Half way down Gia Ngu author makes a U-turn. Read aloud his Declaration of Independence. And continues, past sellers of tubers, onions and garlic. The next day the provisional government convened for the first time. Sellers of carrots, limes and peppers. At Bac Bo Palace. Across from a stall offering the inner organs of beasts a shop purveys hand-painted tea pots in the shape of birds, miniature tea sets in blue and white, porcelain canisters, chopstick rests, sauce bowls. Where it set “urgent tasks” to resolve the problems of illiteracy and hunger.

Larger bowls and platters too, all sizes and shapes, some in pale orange and light green. Postmodernism isn’t afraid of ornamentation. Wooden chopsticks and plastic spoons are also for sale. Because postmodernism retreats from classicism to romanticism. On the rain-dampened surface of the curb, part of a deck of cards has been scattered, most of them face down. The Classical and Modern Periods identified beauty with simplicity. Only five have fallen with their faces up: The Baroque and Romantic Periods identified beauty with complexity. The jack of diamonds, the nine of clubs, the two of spades, the three of diamonds, the nine of hearts, the last of these lying in the gutter.

In his letter to the people Ho Chi Minh proposed: Live crabs in a basin scurrying atop one another. “Let us forego one meal every ten days.” A man in a black leather fedora parks his black Suzuki motorcycle before the entrance to his shop. The rice saved will be collected. Parting the black beads in his doorway, he enters. Then dispensed to poverty-stricken people. Once inside he is visible through the window as he tends a black bird in a cage. “A piece of land is a tael of gold,” he said. Beside the cage is a clock with black hands indicating 7:30. He stirred the country with such movements as “pushing up production.” We pass a woman making salad by grating carrots into already grated radishes and cucumbers.

The country reclaimed land, restored mines and started factories. Our detour complete, we rejoin the main road, at the entrance to which, in a tie-less uniform, his arms folded, stands a soldier. You know, Modernism tried hard, it really, really tried to get rid of conventions. Two women, one pretty, one not so pretty, stroll past, arm in arm. It thought it got rid of conventions, but all it really did was make its conventions invisible. A young girl in an “AK-23” tee shirt enters the market, as author prepares to leave it. Though two million people had died of hunger, by early 1946 Ho Chi Minh managed to stem the famine. A woman touches author on the arm as she offers him a bottle of water.

Reentering the main street (Pho Dinh Liet), we arrive at a larger avenue that leads into a traffic circle. “Sapa bathed in clouds”: Rooftops of the village tiled in orange, gentle hills rising into mountains behind them, the misty clouds barely covering the spires of conifers. Parked at the corner is a tiny red car, a sign across its windshield reading, “Vietnam Museum of Ethnology.” Of the 54 ethnic groups living in Vietnam some are indigenous while others immigrated from neighboring countries. A red-roofed farmhouse sits high above terraced rice fields. Sino-Tibetan, Austro-Asiatic, Malayo-Polynesian. With author’s arrival, the red car makes a U-turn and departs through the traffic circle.

Three beautiful girls of fifteen, sixteen, seventeen in elaborate red headdress, bamboo stalks held in their right hands, look down in modesty. The Kinh people account for 86.2% of the total population, the other 53 groups, called “ethnic minorities,” range from one million to just over 300 people. Yes, Modernism created a lot of dysfunction: nobody disputes that. Mothers in green headdress. We were encouraged to revolt, deconstruct, cut apart our papers, run away from home, and take drugs. Their daughters in pink and green, red and green (“Market Day in Bac Ha”). Not to get married, and so on. The Kinh live mostly near the rivers, where historically they created the wet-rice civilization.

Modernism tore a lot of things apart, but especially the household. A toothless old man on a bicycle stops to sell a map of Hanoi to author, who is looking for the city’s lake. The interesting thing to me is that postmodernism is propagating the dysfunction. Red Dzao people in their brilliant blue robes at the marketplace. Because it actually finds its meaning in dysfunction. Almost all minority groups (except the Hoa and the Khmer) live in midland and mountainous regions. As the toothless old man points, author turns to glimpse the lake itself. Postmodernism is really a result of Modernism. Author takes seat on bench at lakeside only to be accosted by a postcard seller with overpriced wares.

Reductionists often feel as though they are being objective. The Constitution ensures equality in all respects among ethnic groups. But the problem with reductionism is that, once you’ve divided your universe into enough pieces. “H’mong girls in springtime,” delicate cherry branches blossoming behind them. You can’t keep track of them any more. “H’mong girls at the Love Market.” To get a fair price author must bargain for fifteen minutes. The human mind can only keep track of seven objects at a time. “Black H’mong youngsters” in their black leggings and huge silver earrings. The Modernists lost track of something: they forgot what’s important about Literature.

Each of the 54 ethnic minorities in Viet Nam has its own language. The word that’s sweeping U.S. high-school playgrounds and college campuses is “crunk,” a blend of “crazy” and “drunk.” Up to 24 ethnic groups have their own scripts. A hard drinker, loud but not yet a “crunk,” is a “daunch.” Including the Thai, Mong, Tay and Nung. “Wheels,” as they were once called, are now “whips.” Of which eight are used in daily life and taught at schools. An ordinary car is a “ride,” while a large passenger car out of style is not a “whip” but a “scraper.” Namely the Thai, Hoa, Khmer, Cham, Ede, Tay-Nung, Co Ho and Lao scripts. “Good-looking,” male or female, is “bangin’” and the latest term for “cool” is “tight.”

From 111 BC till 938 AD, when Ngo Quyen wrested back national independence, the Vietnamese refused to be daunted and continually stood up against their oppressors, the Han aggressors. Though the popularity of smoking pot seems to be getting stale, the lingo of aging Mary Jane maintains its freshness: Throughout an entire millennium of Chinese domination the ideographic script was used in administrative documentation and so served as the tool of the ruling class. “Dank,” which in Standard English means, “disagreeably damp,” in current slang describes the high-grade illegal product (marijuana), and the adjective’s meaning accordingly can be extended to anything highly rated.

In 1077 the Ly Dynasty fought against the foreign aggressors, sending an army of 10,000 cavalry to defeat 100,000 troops of the Song at a front on the Cau River. On the other hand, the Standard English noun “stress” is used as a synonym for the cheaper variety of weed. In terms of spiritual and educational policy, the dynasty promoted and upheld Confucianism, constructed the Temple of Literature and the Imperial College, taught the classics, held examinations to find the best pupils in the country, and reconciled the three religions (Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism). “I’m not gonna smoke this stress.” The succeeding Tran Dynasty three times defeated the Mongol-Yuan invaders.

What is the latest term for the old “cool”? Though his reign was short, the broad-minded Ho Quy Ly issued a fourteen-chapter criticism of the Song-Confucian ideology, set limits on land ownership and serfdom, put paper money into circulation, adapted the taxation system, diminished clerical powers and restrained feudal aristocrats in order to increase the social labor force. Instead of “cool,” try “tight.” Land was redistributed, surveys of the population and their assets conducted, the exam system reformed and education improved. “Did you see his pimped-out ride? Hospitals were set up, law and order maintained, irrigation and transportation developed. “It was tight.”

Though the ideographic script of the Chinese was taught at schools to train local mandarins and was used in literature and art for about twenty centuries, nevertheless Vietnamese intellectuals devised the Nom script, derived from Chinese, in order to record the actual sound of Vietnamese. The meaning is extended to innocent intimacy with someone: “Charlie’s my boy. We’re tight.” Nom was commonly used from the 15th to the 19th centuries, particularly in literature. The antonym for “tight” is not “loose” but “janky.” Beginning in this period the centralized feudal power of Viet Nam fell into crisis, and the country experienced over two centuries of turmoil. Also spelled “jinky” or “jainky.”

Levinas contends that western philosophy exhibits an often horrific propensity to reduce everything enigmatic, fortuitous or foreign to conditions of intelligibility. This slow developer (it started at least a decade ago) has picked up meanings that range from: Recoiling at the obliterated secrets of the past, the unpredictable events of the future and anything that cannot be rationally ordered and manipulated. “Substandard” to “weird.” Everything must be understood, synthesized, analyzed, utilized. An expurgated citation goes: If something cannot be grasped by the rational mind, then it’s either extraneous or portentous. “That janky camo boy got some stuff on the side of my ride.”

Ten postcard views: Given its perfectionistic drive to impose rationalist categories upon the world so as to realize a state of perfect intelligibility. (1) Two women in conical hats, caught as they stride, each on her left foot, across an intersection filled with passing motorbikes, other women in conical hats. Du XVIIe au XXe siècle, la ville comprenait tout un réseau de marchés spécialisés. Nothing seemingly can resist the rational order of science, the technological order of utility and the political order of justice. (2) A woman has descended from her bike, yellow chrysanthemums in hand, to converse with two other women, one bearing chrysanthemums, the other with a basket of roses at her feet.

À l’Est se trouvait le quartier populaire, la cité marchande, où se concentraient les corporations d’artisans. (3) A rickshaw overtakes two girls, one with her arm about the other’s neck, while just ahead stroll two older women, caught in identical postures, as a woman with a basket of green fruit approaches them from around the corner. Among the many entities that western rationality inexorably seeks to render intelligible are: On y fabriquait des articles de luxe et le commerce y était prospère. God, the individual agent, the historical past, the progressive future, non-western cultures and anything superstitious. (4) The back of a red rickshaw in front of a yellow and white colonial office building.

Au Nord et à l’Ouest se trouvaient les villages artisanaux où l’on fabriquait les marchandises d’usage courant ainsi que les villages d’agriculture spécialisée. Western thought seeks to rationalize the being of God in such a way that it is just a being among beings. (5) Two rickshaw drivers cycle past, each with his head turned to the left, probably to observe approaching traffic. Le quartier s’est développé dans un environment parsemé de nombreux lacs et étangs. It strips individual persons of all the facets of their unique existences. (6) A woman walks by, heavily burdened with a shoulder bar, from which two full baskets of fruit are suspended, as two more women walk their bicycles together.

Il était cerné par la rivière To Lich au Nord, par le fleuve rouge à l’Est et par le lac de l’Épée restituée au Sud. It endeavors to expand memory so that nothing past is forgotten and to thrust itself into the future so that nothing is undivinable. (7) Beneath sunlit mimosas two women, each bearing a basket on her head, turn to address one another. Le premier marché ainsi que le premier noyau d’habitations étaient situés au croisement de la rivière et du fleuve. (8) A westerner in black shoes and black shorts, a bottle of water carried in his right hand by its orange handle, picks his nose with a finger of his left hand, while, in a red tee shirt with a large yellow star, he passes a café surmounted by a Tiger Beer ad.

Finally, foreign traditions that might not contribute to the perpetual march of rational success are either crushed, distorted or ignored. (9) A woman in grey pants suit passes a street sign reading “Pho Cau Ge” as she approaches an orange-shirted woman bearing baskets of green oranges. L’embouchure de la rivière To Lich servait de port et plusieurs petits canaux parsemaient le quartier. (10) A girl in black pants, red jacket, her two pole-suspended baskets lidded, strides by with a plastic bag of oranges in her hand. As the Cold War attested, and several “terroristic” or “rogue” nations have recently discovered (to describe this perfectionistic urge Levinas uses the term “being’s move”).

Random street elevation. The dignity of being the ultimate and royal discourse belongs to western philosophy because of the strict coincidence of thought in which philosophy resides. Hanoi Old Quarter. And the ideas of reality that this thought thinks.

(1) “Com Bia Ha San,” the restaurant’s interior revealed. Les maisons du quartier sont caractérisées par leur façade étroite et leur longueur considérable, d’où l’appellation est “maison-tube.” Beside a glass case filled with bowls and plates, atop which a tea pot and a green scale, is the menu, each item indicated with a red bullet and descending as a vertical list: “Com Bia, Com Dia, Com Bat, Com Hop, Com Chay.” For thought, this coincidence means not having to think beyond what mediates a previous belongingness to “being’s move.” “Lau Ram, Lau Chay, Lau Hai San, Lau Thap Cam, each item indicated with a red flower before it. Above the restaurant rises a corrugated roof.

(2) In letters reading from top to bottom: “Internet” (on the left), “Netzone” (on the right). Leurs façades varient en moyenne entre 2m et 4m, tandis que la longueur se situe entre 20m et 100m, pouvant atteindre dans certains cas 150m. Within the doorway an inner-lit sign reads: “ADSL, Service, Print, Scanner, Burning CD, Internet font.” Or at least not beyond what modifies a previous belongingness to “being’s move.” Above the shop’s sign (“Vittel Internet S@i Gòn”) rises a second story, doubtless the famous “sleeping room”; above it, a third story, balconied, with large luxurious pots on the railing, within whose exterior wall niche sits the Bodhisattva. Such as formal and ideal notions.

(3) The adjacent house to the east is dressed on its lowest floor in wooden planks, long ago painted rust-red. Dès le début du XXe siècle, l’architecture des bâtiments du quartier s’est mise à se modifier en adoptant des éléments d’architecture occidentale. Above the doorway a talisman, a wide roof extending well out over the sidewalk. Tels les balcons et corniches, baies en arcades, baies rectangulaires, etc. Instead of an “intermediate” story this house has a story of normal height, shuttered in wood once painted pastel green. For the being of reality, this coinciding means in itself to be illuminated, is just what having meaning is, what having intelligibility par excellence is. The roof was once red.

(4) “Tropical Tours,” read the bright carmine letters of the next building’s first-floor sign (against a rolling green surf), which completely covers the building’s “intermediate” story. That is, the intelligibility underlying every modification of meaning. Les toits en pente sont, quant à eux, disparus derrière des façades-écrans. On the third floor rises the “Moonlight” (vertically lettered, in white on blue) “Hotel” (horizontally lettered, in white-outlined red on the same blue ground). Les maisons comprennent maintenant 2 étages, le commerce se trouve au rez-de-chaussée et le second, désormais accessible par un escalier en bois ou brique, sert de pièce d’habitation. A guest’s yellow shirt and white socks hang on the window grate.

Rationality has to be understood as the incessant emergence of thought from the energy of “being’s move” or its modification, and reason has to be understood within the context of this rationality.

MM: I have been writing about modern Vietnam, about life on the streets of Hanoi. Now I would like to learn more about the history of your capital, so I have come to visit your “historical house.” Please tell me your name first. (It might be well to discuss “being’s move” in more generally Levinasian terms.)

Thieu: My name is Thieu. The “ontology of power” is the grandiloquent term that Levinas assigns to this salient aspect of western metaphysics.

MM: You must know a lot about Vietnamese history. And there is some urgency to his claim that metaphysics has been interested primarily in totalization. What do you think is most important for me to know? The reduction of any form of difference to sameness.

Thieu: I don’t know. For the purpose of enhancing the powers of rationalization.

MM: Tell me something that you yourself find interesting about Vietnamese history. Under ideal conditions knowledge is perfectly adequate to reality.

Minh: I know a little, and I like the history of Vietnam! The totalizing tendency of western metaphysics. It’s very important for the pupils in the school. Comes in the form of a dual aspect theory of power.

MM: Could you tell me a little, then, about the period when the Chinese were in Vietnam, for 1000 years? On the one hand, when our knowledge is adequate to reality. How do you feel about the Chinese occupation? Then everything is reduced to sameness.

Minh: I don’t know much about it. Which gives an epistemological mission to reality.

MM: Please tell me your name. On the other hand.

Minh: My name is Minh. It is when we discover the metaphysical principle of difference that we are able to comprehend the uncomprehended.

MM: Tell me something about what the Chinese did in Vietnam. It is then we can reduce difference to sameness by other means.

Minh: [In Vietnamese Minh consults with Thieu.] This itself facilitates principles of knowledge, which in turn give a purpose to metaphysics.

MM: Minh, you cannot answer in Vietnamese! Epistemology and metaphysics. You must speak English or French or Mandarin! Are enfolded, then, in the very conditions. You know, I cannot understand Vietnamese. Of the ineluctable progress of totalization.

Minh: OK, when the Chinese stay here, about 1000 year ago [sic], they want to have the country, and the people in Vietnam, um, belonged . . . Selfhood precipitates the power to become through the effects of totalization.

MM: To China. The more adequate its knowledge. At that time did everyone have to write in Chinese characters? The more reduced the differences of reality. Did everyone have to speak Chinese? Then the more power over reality it has. The Chinese, I know, instructed the Vietnamese in the teachings of Confucius. And therefore the more perfect it becomes.

Minh: Yes, when the Chinese were stay here [sic], the Vietnamese people, they speak Chinese. The self comes to be at once detached from and empowered over the reality that it has reduced and adequated in its pursuit of unmitigated knowledge.

MM: And what about the French people? When they came to Vietnam, did they make the Vietnamese people speak French? Self-sufficient autonomy is achieved when the self is distanced from the world, empowered over it and masterfully subordinated to universal laws that give it purpose and justification.

Minh: French people? Um.

MM: The French people made everyone in Vietnam speak French, didn’t they? Hence, not only has selfhood advanced its means of access to reality, it has also transformed its status in that reality as well.

Minh: OK, in late 19th century and early 20th century a lot of people in the Vietnam, they speak French. Of course, here is no rational guarantee that reduction and adequation will leave selfhood detached and empowered. And they build hou[ses] the similar architect in France, in the Old Quarter. If only because this totalizing process has effects upon the self as well as its reality. Has some theater and cinema and building like in French [sic]. In its ability to rise above its existence through conscious activity, its own individuation is reduced and adequated as well.

MM: Let me change the subject for a moment. Who do you think is more beautiful, French girl or Vietnamese girl?

Minh: [Laughter.] Vietnamese girl!

MM: Of course! [Laughter.]

Minh: [More laughter.] This is tantamount to the claim that the more human subjectivity knows of its reality and assumes power over it, the less it retains its uniqueness and the less power it has over it own determination.

MM: And what about food? The self loses itself, when it progressively disappears into the totality that it has created for itself. Do you like French food or Vietnamese food?

Minh: Some time I like, uh, French food. But I [also] like Vietnamese food, because I eat all the time! We speak of the self as if we were speaking of a unique individual, when in fact we are referring to a principle that renders uniqueness intelligible.

MM: But you are so thin! . . . Anyway, after 1954 the French left Vietnam, and then Vietnam became Vietnamese again. Totalization entails that there be nothing to the self that could remain unreduced and non-adequated: It was at this time that people began to speak Vietnamese again instead of French. There is no aspect of the self’s “interiority” that has not been reduced to the totality of rationalism. Is that right?

Minh: After 1954, the French, they left here. Emotions, religious beliefs, sexual pleasure and any other intimate aspect of the self is part of the technical economy of rationalization. The Vietnamese, they speak Vietnamese. [Laughter.] Nothing being outside. And, uh . . . Or inside this totality. But, uh . . . That is not interpreted. Some people, they like architect in French [sic]. Through the values of rational reduction.

MM: So in certain ways, might we say, Vietnam is better off because of the introduction of Chinese culture and French culture? No individuality or specificity. Since, as a consequence, the Vietnamese have three different cultures. No enigma or pure transcendence.

Minh: Yes. Could possibly sustain itself. In Hanoi, some people like the French, but in the South they like the Chinese. If the ideal, then, of modern western rationalism, of the “ontology of power,” were to obtain.

MM: How interesting! Now I notice that you are not speaking Chinese or French or Vietnamese, but instead English! The potential of anything specific being subversive or disruptive of this ideal is eradicated. Why are you speaking English?

Minh: [Laughter.] Because now English is, uh . . . One might say that life, then, would lack the poignancy that makes it worth living . . . uh . . .

MM: An international language?

Minh: Yes, an international language. So, as many many country they speak English, I have study English, because I want to understand about the country in the world. However, Emmanuel Levinas is not exclusively a critic of modern western rationality.

MM: Then, after the period of French colonialism came the “American War.” What can you tell me about the American War? He is more widely esteemed as a visionary thinker who explores the neglected status of ethics.

Minh: When the American, they stay here, they has many bomb in Hanoi, and many many building and pagoda and cinema is ruined. He contends that his is no mere ethics among competing ethics.

MM: Yes, this was a great tragedy. But rather an “ethics of ethics.”

Minh: And the people, they have terrible life. Roughly speaking, the study of the manner in which foreignness, inexplicability and unpredictability shape the human condition.

MM: Which was an even greater tragedy, wasn’t it? Despite the often arrogant demands of our vaunted rationalism.

Minh: And the economic in Vietnam is slow slow. Cannot develop . . . For Levinas, the human condition is indeed shaped by rationality, preeminently in the forms of technology and politics.

MM: So all Vietnam history is very bad. But it is most radically dependent upon the very foreign elements that this rationality strives to render intelligible. Much of Vietnam history is about war and tragedy and colonial domination. What about today? How do you like living in Vietnam today?

Minh: [Laughter.] Yes!!! I love Vietnam today! The self is torn by an irresolvable and irresistible strife between the order of the “Same.”

MM: So do I! Which strives to totalize everything under the illumination of reason.

Minh: But I think in the future, the government, they have some program. And the order of the Other. They can change some streets in the Old Quarter. In which vital parts of human existence remain necessarily unillumined. Maybe no car and motorbike in the Old Quarter!

MM: That would be very nice, wouldn’t it? The self and the self’s word are determined by enigmatic phenomena. What about your own motorbike? That remain unknown to us and irreducible to rational criteria in the totalizing project.

Minh: But if in the future, the government law about motorbike, I cannot ride. In a sense, they are aspects of human existence that can never be known.

MM: Maybe it would be better just to walk in the street. And indeed, it is best for us that these things continue to keep their secrets.

Minh: I can go by bus. [Laughter.] That is what Levinas means when he iterates that infinity always resists totality.

MM: Now tell me, Minh, when are you going to get married? When the “other” always “overflows” the “same”:

Minh: [Laughter.] Why?!? No matter how much we come to know. Why do you want to know? It is always something resisting.

MM: I want to know about your family! Or disrupting the perimeters of the known.

Minh: [Laughter.] Now, my parents, they want me to get married.

MM: Does your mother tell you this every week?

Minh: Yes, but now I don’t find a good man. Only through an exploration of this over-flowing, this resistance and disruption.

MM: Well, I wish you luck! Can the ultimate principle of ethics be articulated:

Minh: [Laughter.] That is to say, responsibility.

MM: I think it should be very easy for you to find a good man. Isn’t this like the “meaning of meaning”?

Minh: Why do you think so? Or the “emptiness of emptiness”?

MM: Because you are so beautiful! And so smart! And so lovely! Perhaps a common translation of his idea will sober the cynic’s smug incredulity:

Minh: [Laughter.] Thank you . . . but I don’t think so. I think in my life to find good man is very difficult. [Phone rings.] “The ethics of responsibility.”

MM: Now, you must answer the phone! (Maybe he is calling.)

Minh: Hello?

The Van Mieu, established in 1070 AD, is a monument to Confucius. Second random street elevation, non-touristic neighborhood, Hanoi. While scholarly culture flourished in the cities, popular culture, with its nationalist calling, often despised by a westernized elite, took refuge and was perpetuated in the countryside. Similar to the mieu, or Confucian temple, found both then and now in villages throughout Viet Nam. A motorcycle (“Dylan 150”) pulls up to a professional cell phone op seated on a black plastic sidewalk stool, while adjacent seller of coffee beans prepares for author a cup of java. In 1075 the Royal College opened on the same site to prepare princes for the governance of the country. Spirituality was guarded by ancient popular beliefs and the unified triple cult of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism. Having finished his call, the guy on the Dylan departs, his girlfriend seated behind him, her arms circling his waist. This explains why Christianity had difficulty implanting itself in Viet Nam. A year later the college was renamed School for the Sons of the Nation.

Across-street view into pharmacy/clinic, its sign above a white circle on a blue ground, within which an orthodox red cross, beneath which, in green, the word “Yersin.” Gaining a foothold in the 17th century, Catholicism, unlike Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism (other imported religions) was unable to clothe itself in the national character. To the clinic’s right, a paint store, its sign, not surprisingly, all in Vietnamese. For 700 years, until the Nguyen dynasty moved the capital and the university to Hué, the school fostered some of Viet Nam’s greatest statesmen and men of letters. To the left, “Yen Nhi / Collection,” a fashion outlet, its window filled with silver Christmas ornaments, a green wreath hung half over the window, half above the open door. The principle reason for this was intransigence. In its present form the Van Mieu is modeled after the Temple of Confucius at Qu Fu in China, with the five courtyards representing the five essential elements of nature. Christianity allows no other divinities than its own and bans the cult of ancestors.

To the left of the fashion boutique is a store selling cookies, crackers, cigarettes, soft drinks, candy, wine and bottled water. A visitor’s walk through the temple grounds provides an introduction to the history of the country, to Confucianism and to the special place that education and literature have long held in Vietnamese culture. To the right of the paint store, another paint store. In addition, Vietnamese Catholicism is marked by its “original sin”: The complex began as a temple to both Confucius and the Duke of Zhou, a member in the 11th century of the Chinese royal family. It appears anti-nationalist, because from the time of the French conquest the cross has served the sword. (The Duke of Zhou is credited with originating the teachings that Confucius developed 500 years later.) The second stories are all different: During the colonial period and the two national wars the church sided with the foreigners. A bricked wall into which sliding glass doors have been fitted; a dilapidated house front, boarded up; an elegant balcony; a facade of French windows and shutters.

Vietnamese-ness in brief: Pedestrians must use the street, for in this neighborhood the sidewalks are all blocked. Five courtyards separated by brick walls comprise the interior. (1) The predominance of the Vietnamese ethnic majority, which inhabits the lowlands. A convoy of rickshaw-driven Korean tourists passes, four vehicles followed by another four, an older Korean man fanning himself with a Hangeul newspaper. In Confucian as well as Buddhist numerology the number five has a special place. (2) The Southeast Asian substratum in Vietnamese culture, onto which foreign cultural elements, Asian as well as western, have been grafted. A guy scoots by with two girls on the back of his motorbike, followed by another girl in a pink sweater on her own motorbike, an expensive handbag nestled between her feet. There are five essential elements, five basic virtues, five commandments, five sorrows, five cardinal relationships and five classics. (3) The principle of repulsion / attraction governing the Vietnamese assimilation of foreign cultures.

Walking up the street in the opposite direction a woman in her thirties, dressed in conical hat and black super sleeves, pushes on by in rhythmic motion, as she bears on her shoulder pole the burden of two baskets, one filled with oranges, one with apples. A central pathway divides the complex into symmetrical halves as it leads the visitor through the different courtyards to the temple altar. In the period from 179 BC to the mid 19th century Chinese acculturation demonstrates this principle. (In the shoulder pole with its inseparable baskets, the doi quang, has been seen the image of conjugal fidelity.) Each courtyard is connected to the next by three parallel gates that bear names symbolic of advancing wisdom. In the period from the mid 19th century to 1945 French acculturation again demonstrates the principle. Three motorcycles arrive, each with a large cargo of several boxes. Parallel Chinese couplets are inscribed on the side columns of these gates. Resistance to the Americans and the subsequent absorption of American culture also demonstrate the principle.

A white man, wearing a tie, a black daypack strapped to his back, walks by on his way to lunch. A walk through the courtyards of the Van Mieu recalls the Confucian scholar’s progress in following the path to knowledge. The great national upheavals of revolution, war and their aftermath. Author passes through the gateway, pleasantly illuminated by the mid-day sun. Including the drama of integration into the world community. We have left behind in the outer courtyard five recently planted palm trees, on either side of the path. Has turned the cultural setting of Viet Nam upside down. As author enters the second courtyard, a woman wearing a tiger striped top exits through the portal. In a world full of movement and transformation. We traverse the first courtyard (“The Entrance to the Way”), bordered on each side by five clumps of poinsettias. Viet Nam. The sound of vehicular traffic has diminished. Subjected to a wide range of influences. A girl with a dragon on her tee shirt takes out her cell phone. Is searching to redefine, without repudiating, its identity.

The journey begins with respect. Inside the second portal a plaque explains the program of instruction at the National College. Each of the two tallest pillars is topped with a mythic beast, the Ly, which has the power to distinguish right from wrong, good from evil. They paid special attention to “the Four Books,” it says (the Da Xue, the Zhong Yong, the Lun Yu, the Meng-zi). For Derrida the phenomenon is the question, for there is no phenomenon without at least the possibility of the question, the possibility of posing questions about the phenomenon, including the phenomenon of the question, in a philosophical language with all the terms of opposition and logical constraint. But they were also examined on the five pre-Confucian classics (the Odes, the Annals, the Rites, the Book of Spring and Autumn, the Book of Changes), as well as ancient poetry and Chinese history. I thus propose to follow here what to my eyes is Derrida’s unfailing fidelity to the question, a fidelity that can never be reduced to the question and yet cannot be expressed without it.

We have passed into the Great Courtyard, where a child’s plastic ball, striped red and white, has been left behind on the scruffy St. Augustine’s grass. I will follow this fidelity to the question by asking about the way Derrida himself follows the question in another, that is, by following Derrida questioning Levinas on the role of the question and its relation to the phenomenon. Author peers into one of the two symmetrically designed lotus ponds, over which a large central banyan is branching out. We shall see that from beginning to end it is the question of the phenomenon and the phenomenon of the question that ceaselessly returns. A mother, ethnically Vietnamese, explains in English to her ten-year-old daughter, whose long dress in black and red is cut from the same piece of cloth as the mother’s, what the guide has just conveyed to the mother at great length in Vietnamese. “Among the doctrines of the world, ours is the best and is revered by all culture-starved lands,” says an inscription, “Of all temples devoted to literature, this is the head.”

A Vietnamese guide, in black sandals, black pants, black shirt and black jacket is lecturing to three French tourists on the temple’s architectural design (we have reached the “Puits de la Clarté Céleste,” he tells them). Oriented or driven each time by a new concern within the work of Levinas, the question of the question always returns, the question of the relationship of philosophy as the realm or regimen of the question to that which exceeds philosophy, the relationship of ontology, if not phenomenology, to ethics. Virtue and talent are the keys to passage from the first to the second courtyard. Inside the third portal two Vietnamese college students are mechanically copying its bas-relief designs. Each time it is a question of the same and of something that resists both the question of the same, the possibility of philosophical language to receive or welcome what precedes or exceeds it. Author turns toward a portico filled with turtles bearing large plaques on their backs, heedful of a sign that reads, “Do not write, draw, step or sit on the Doctor’s Stelae.”

Cautiously he takes a seat, cheered by a smile from an eighteen-year-old Vietnamese girl in bright yellow sandals, who is seated with two of her fellow students, as a fourth girl with red daypack joins them for lively conversation. Two carp atop the simple gate symbolize students on their way to becoming mandarins. Meanwhile a rough French woman of 65 in grey and white basketball shoes takes a seat with her 70-year-old husband to flip the pages of their guide. From the publication of “Violence and Metaphysics” to his final Adieu it is a question of the necessary violence of ontogeny, a question of the inevitable and perhaps salutary interruption of the ethical relation, a question of the hospitality that can ever be offered to the Other once this relation is interrupted, a question of the welcome that can ever be reserved for it. A heavy-set Korean woman helps her pudgy daughter unfurl a bright green vinyl hammock only to watch as the daughter repacks it in its black plastic case, their Korean-speaking Vietnamese guide all the while keeping a respectful distance.

Entrance to “The Courtyard of the Sages” is through the Dai Than Mon, or Gate of the great Synthesis, which may also be translated the Gate of Great Success. At last the remainder of the Korean tour group catches up and draws the pair into their collective progress. The elements of the Confucian doctrine, the learning of the past and knowledge of Buddhism and Taoism are brought together here to complete a scholar’s erudition. Another of the eighteen-year-old Vietnamese girls turns about to reveal a sunflower hair catch holding her ponytail together, its five yellow plastic petals surrounding an orange center. Reading Derrida over the course of the last three decades, today, in the light of Adieu, we may begin to understand “Violence and Metaphysics” as a great text on hospitality, on a hospitality that is always granted by means of the question but can never be reduced to it. While the second eighteen-year-old student, she too seated, is turning to smile at author, a schoolmate appropriates one of her sandals to serve as her own improvised seat on the terrace.

Ahead lie the Gate of the Golden Sound and the Gate of the Jade Resonance. As we enter the Courtyard of the Sages, two middle-aged Vietnamese women dressed entirely in black make their appearance, one in an appliquéd blouse with transparent gauze sleeves. Yes, thirty years before Adieu, “Violence and Metaphysics” was, or will have been, a great text on hospitality, just as Adieu, as we shall see, can be read as a great text on the relationship between violence and metaphysical language, metaphysical understood here in both its Levinasian and its more traditional sense. Next appears a three-person group consisting of (1) an overweight 60-year-old Caucasian woman in short grey hair, (2) a Vietnamese woman of 30 in tight black pants and a sexy top, violet-and-black, (3) an eight-year-old blond girl in a lavender “I Wanna Dance” tee shirt, a yellow smiley face at its center. Historically the fifth courtyard served as a university, equipped with student classrooms, dormitories and cooking facilities, along with a print shop for school textbooks.

Today the courtyard is adorned with scraggly topiary sculptures resting uneasily in three urns at its entranceway, where a German-speaking Vietnamese guide in authentic accent has taken up his station to lecture on what he is calling the “Platz der Ceremonie.” “Violence and Metaphysics” can today be read as a series of reservations or questions posed to Levinas concerning the relationship between philosophical language, the language in which Levinas never ceased to write, and its ability to accept, receive or—and I’m now citing Derrida from 1964—“welcome” that which is wholly “other” within it. Meanwhile an English-speaking guide identifies the frangipani leaves and branches overhead, as sunlight fills the courtyard and tourists of many nationalities approach the altar to Confucius to practice their amateur photographic art. How, Derrida was asking more than thirty years ago, can Levinas’s language be hospitable to that which is foreign to it without posing serious questions, that is, without posing serious questions to this “other” . . .

. . . without therefore requiring an answer that would translate the language of the foreigner or stranger—the question that is the stranger—into the language of the host, that would transform into a phenomenon that which exceeds and resists all light? In traditional ao dai—pink, yellow, magenta, salmon—a passel of four Vietnamese girls materializes from nowhere. Modern Vietnamese critics of this form of education. A tiny fly settles on author’s pant leg. Object to its focus on memorization, its lack of attention to practical learning, its neglect of Vietnamese history in favor of foreign (Chinese) history and culture. Two Japanese girls in jeans and black tee shirts—one reading “A Fire Within,” the other, “Striving Towards Altruistic Realm”—are joined by two more girls, in green and white tee shirts, who photograph them. They speak of its irrelevance, of “sitting on the bridge in Do and talking of the land of Moc.” Author, leaving behind this photographic frenzy, strolls toward the sanctuary of Confucius, who, on a plaque, is described as follows:

“Intelligent, calme, passionné d’études, il était célèbre pour son érudition avant l’âge de trente ans.” To circumscribe these questions of language and hospitality, Derrida spoke, already in 1964, of the relationship between inside and out. We have stepped out of the sunlight and into the temple. “Des élèves venaient de partout pour suivre son enseignement.” Celebrant-worshippers bow in reverence. “À partir de 54 ans, avec des disciples, il voyagea dans pleusieurs principautés pour parfaire ses connaissances et propager son savoir.” “Will a non-Greek,” he asked, “ever succeed in doing what a Greek could not do, except by disguising himself as a Greek?” To reach the image of Confucius we must cross a very narrow courtyard; stepping over a lintel, we confront the porcelain image. “À 68 ans il retourna à Lo pour écrire et enseigner à près de 3000 disciples.” Two red candles burn before the red-robed sage. “Il mourut à 73 ans.” Two bouquets of roses have been inserted into two bronze vases atop the modest altar, beside which rise two red columns.

MM: Tell me about your personal background. When were you born, and where?

LTV: I was born in 1956 in a small city on the outskirts of Saigon.

MM: And what sort of artistic education did you have?

LTV: Till the age of thirteen or so I studied art in provincial schools and then enrolled in the École des Beaux Arts Nationale in Saigon.

MM: And when did you finish your studies there?

LTV: In 1970.

MM: This must have been a difficult time to be in Vietnam? When were you able to leave?

LTV: I left Vietnam for Canada in 1980.

MM: How did you support yourself financially during the early years of your career as an artist in Canada?

LTV: The first job that I found was in a silk-screen workshop, where I used skills that I’d acquired in Vietnam.

MM: And did you continue your formal education in Canada?

LTV: Yes, I enrolled at the University of Quebec in Montreal.

MM: When did you graduate?

LTV: I finished school there in 1987.

MM: Having studied art in both Saigon and Montreal gives you a double perspective on the emerging global art scene. We know that you’ve worked as a painter and performance artist and that you’re part of the mail art network. Have you practiced other forms of art?

LTV: I’ve worked in mixed media, and I’ve done a good many installation pieces.

MM: How did you become involved with mail art?

LTV: In New York City I met Ray Johnson, the founder of what at the time was called The School of Correspondence. Shortly thereafter I began corresponding and exchanging works of art with him. This led to further contacts around the world. Through networking I have collaborated, exchanged ideas and implemented these ideas as works of art.

MM: What other art movements were influential in your development?

LTV: Among the historical movements Dada and Surrealism were the most influential.

MM: What did you find most useful about the tradition of Dada-Surrealism?

LTV: That’s a good question. I would say that Dada-Surrealism was perhaps most influential in my conception of performance art. But I was also influenced by Dada poetry and by the Dada artists’ use of collage, a medium that they shared of course with the Cubists and the early Surrealists and one that has subsequently been widespread.

MM: You’ve operated, now, for many years as an artist based in Montreal. To what extent have you maintained your early contacts in Vietnam, and how have you managed to stay in touch with people in Vietnam while living in Canada?

LTV: Over the years I’ve kept in touch with classmates from art school, mostly by mail. We’ve also exchanged works of art, along with information about how our careers were developing. We talked about whom we’d met, what we were doing, and so on. More recently the Internet has made it easier to maintain this sort of contact.

MM: As you’ve returned to Vietnam from time to time what changes have you observed in the recent cultural development of your native country?

LTV: During my first trip back I was amazed at the changes that had taken place, mainly because Vietnam had been transformed from a country at war to a country at peace.

Everything was new. My family had changed their activity, my friends were all doing something new. Moreover, the country itself had changed and begun to develop in unpredictable ways. Vietnam has become much more international and has now begun to cultivate contact with the outside world. With new commercial relations has come a new interest in commercial art, both from abroad and within Vietnam. International relations, first with the French, and now with the Americans have been restored.

MM: Throughout the course of your life in Canada, then, you’ve maintained a parallel interest in the development of Vietnamese art. You must have noticed tremendous changes over the past thirty years. Tell us something about this.

LTV: When I attended the School of Fine Arts, the faculty was heavily influenced by the French, especially by work being done in Paris in the post-war period. Many of my teachers had gone to Paris to study, and they’d returned with images of contemporary French art along with books about the Impressionists, the Cubists, the École de Paris, and so on. After Vietnam’s victory in the American War all this gave way to a new interest in social realism, and the new emphasis on politics controlled art schools and to a large extent the whole production of art from 1975 to about 1990. Gradually, however, in the ’90s réalisme socialiste gave way in turn to a more liberal approach. Vietnam opened the window, if not the door, to western countries and became again receptive to western aesthetics. After the renewal of French influence came the American influence, beginning with Pop Art.

MM: So we might say that since 1990 Vietnamese art has generally been open to new art from the West, especially so for you, since you’ve been actually living in the West. How, as a Vietnamese artist, have you responded to western influence? Has it been a problem for you, gradually becoming so westernized, to maintain your identity as a Vietnamese artist? In short, how can one continue to be a “Vietnamese artist,” if one lives in Canada?

LTV: Well, during this period, over the past fifteen years, as an artist I’ve really been neither Canadian nor Vietnamese, because I’ve concentrated so much on networking with artists all over the world. These include people in Italy and France, in the USA and Japan. So, though I live in Canada and return to Vietnam, my range of contacts is much broader. In time I hope that artists in Vietnam can participate in the same sort of networking. Art in the world of the 21st century really has no borders.

MM: I agree that art has become internationalized, but not all artists are as literally international in their activity as you are. By traveling back and forth between Vietnam and Canada you are different from, say, a Canadian who’s grown up in Canada and practices his art in Canada, or a Vietnamese who’s stayed in Vietnam. In addition to your Vietnamese training, you have family and artistic colleagues in Vietnam. But you live in Canada. You have cultural roots and national ties in one place but operate as an artist in an entirely different place. What can you tell us about the continuing influence on your work of Vietnam, of your early life, of your education, of your native cultural tradition?

LTV: When I began to study in Vietnam I practiced traditional Vietnamese arts, such as wood-block printing and lacquer painting. But when I arrived in Canada I was cut of from these sources of inspiration and had no ready access to such materials and traditions. So at first I gave up these techniques. Later on, however, I began to reintroduce traditional Asian motifs into my work. I began, for example, to give a lot of thought to the Chinese tradition of the five elements, to the tradition of Yin and Yang; and I returned to my earlier Buddhist practice. From these sources I drew inspiration, and I began to get new ideas, but I developed the form of the resulting expression in essentially western ways.

MM: We’ve been talking about you as a Vietnamese artist, as a Canadian artist, as a Canadian who often returns to Vietnam, and as a Vietnamese who lives in Canada. In a way you’re a model of the contemporary world artist, the artist who through networking and travel cultivates and maintains a global consciousness. How, do you think, has this sort of activity changed the nature of art itself in the late 20th and early 21st centuries?

LTV: Let me return to the subject of my formal education. When I began to study in Vietnam with people who had just returned from France, Paris was still a lively source of inspiration, and I profited from working with people who’d received French influence and were able to transmit it. But as time’s gone by I’ve been eager to enlarge my exposure to influences, and networking has enormously facilitated this. The teachers that I had in Vietnam are now unknown in Paris, and as Vietnamese artists they have relatively small reputations. If one aspires to a larger international reputation, one must take measures to escape from this earlier model, it seems to me. Once my Vietnamese teachers had established their initial contact with another world, they allowed it to lapse; they failed to maintain it, or were forced into isolation. It’s important to refresh one’s contacts and constantly expand one’s horizons.

MM: Might we not also say that the work of art no longer exists within a merely local or national context but rather in the 21st century must establish itself with an audience that’s developed a more international conception of things, acquired on a daily basis, if only through contact with the media? Perhaps the contact with French art that was once so valuable, with the great movements of the later nineteenth and earlier 20th centuries, is no longer so valuable. Ironically, the French, who earlier had been such internationalists and who in turn had achieved such international recognition, have now become much more provincial, in their politics, in their social and cultural assumptions. It’s hard to think of many people in the early 21st century who are greatly influenced by contemporary French art, though of course French ideas continue to have their appeal for many.

LTV: Yes, I think that for many practitioners of the arts the Americans have replaced the French as a source of inspiration.

MM: So you’re saying perhaps that in recent decades the center of the western art world has shifted from Paris to New York and perhaps from New York to L.A. or to more diversified centers in the USA. Many of course feel that America is no longer the center of advanced artistic activity, if it remains a culturally dominant force. Others feel that the center of the art world has now moved all the way across the Pacific, so that today Tokyo or Osaka or perhaps even other Asian centers are providing the kind of inspiration that was once identified with Paris or New York. What do you think of the new art that you see coming out of Japan?

LTV: Well, when I think of Japan I think of individual artists and individual movements, such as Gutai (or concrete art) in the mid fifties. The first performance art at this early period originated in Japan. Since that time there’s been a great originality in Japanese thinking, especially in avant-garde artistic circles.

MM: Yes, the contemporary Japanese are very original. But I’m thinking not so much of individual Japanese artists or movements but rather of Japan as a center of culture, as a place where fashion and personal style are important, where money is available for all sorts of activity. If one lives in Asia, as I do, every place that one visits has a lot of people in their twenties who are listening to Japanese music or reading Japanese comic books, usually in preference to American music and popular entertainment. When you go to a beauty parlor in Thailand or Taiwan, for example, you find that people are having their hair done according to Japanese trends, or in department stores and fashion shops are buying clothes being worn in Tokyo or Osaka rather than Paris or Milan or New York.

LTV: The Japanese are also very influenced by western style.

MM: Yes, this is true. The last time that I was in Tokyo I happened to see on TV a learned panel discussing the American Western (Cowboy) Movie of the 1950s, for which experts from all over Japan had been convened. But what I’m thinking of is somewhat different. With all its wealth (despite what we hear of financial crisis), the Japanese have become the new patrons of art, of collecting and distributing modern and contemporary art. This, in combination with their more popular influence in matters of taste has made the Japanese the style setters that nineteenth century Parisians and 20th century New Yorkers once were. Only Hollywood has a comparable or greater influence worldwide.

LTV: Yes, I see what you’re saying.

MM: Now this is only my second trip to Vietnam, but earlier in Saigon, and now in Hanoi, I’ve noticed new Vietnamese painting of a sort that I’d not seen in art magazines, even those devoted to contemporary Asian art. This expressionist, symbolic art is like nothing else in the several dozen countries around the world that I’ve visited over the past few years. Tell me, where does this new painting come from, these pictures with red skies and yellow houses and blue streets? Is this an indigenous art, for it doesn’t seem to me dependent upon American, much less European models?

LTV: This new painting is primarily a commercial art.

MM: Yes, I notice that it’s selling well in Saigon and Hanoi. But its commercial success seems to me a function of its originality. These Vietnamese painters have gone beyond any French or American models, or at last have fully assimilated them, and are now creating something new. What are the Vietnamese, or more generally Asian, roots of such strong primary colors, for example, of this new expressionism?

LTV: When you talk about the use of primary colors, this comes from a very traditional source, the five-element theory of Chinese tradition and its corresponding colors: yellow, red, blue, black and white.

MM: I’m aware of the five-element system, and I’m also familiar with five colors as one sees them, for example, in the street signs of Taipei. But what I’m trying to get at is the original character of this new Vietnamese work. What is it for you that makes this painting Vietnamese? And what is causing such a great burst of originality in Vietnam?

LTV: Well, the same color sense we can also observe in contemporary Korean painting. Again, I think the phenomenon has no borders, is not local or national. The Vietnam painters in a sense are leaping over a common Chinese influence or boundary and bonding with Korean painters in this use of color.

MM: Very interesting. You know, it seems to me that here we have an analogy between the artistic activity of Europe in the nineteenth and early 20th centuries and the artistic activity of Asia in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. The center of artistic vitality in the world may be shifting. What do you see on the horizon for the 21st century, in Asia, in Southeast Asia and more particularly in Vietnam?

LTV: I think things will improve in Southeast Asia.

MM: I’m also very struck by what I understand to be a lively culture developing in such a hard-line Communist country as Vietnam. This of course is not the case in North Korea, or Cuba, and artistic expression in China is still limited. But here in Vietnam, fashion and entertainment and even high art seem to be on an upward curve. How can one explain this?

LTV: I think the explanation lies in the two Vietnams, North and South. The South, the center of artistic vitality, was not originally Communist, and though it’s now technically so, the South has remained the center of an artistic vitality that the whole country wants. So the North once again has begun to adopt the fashion and art of the South as its model.

MM: Well, our time’s up, and I’d like to thank you for your insights into Vietnamese art.

LTV: It’s been a pleasure.

“Ladies and Gentlemens [sic], thank you for choosing Odyssey Tours.” Hanoi travaille à limiter le taux de natalité (Le Courrier de Vietnam, Mardi 29 décembre 2004). “From Ha (river) Noi (city) to Ha Long (dragon), 160 kilometers.” Alerte. We have boarded a second bus and are still awaiting our departure. La ville de Hanoi connaît une forte croissance démographique. “If you wonder something or don’t understand anything, just ax me.” Ansi, elle figure parmi les 38 villes et provinces du pays, dans lesquelles le taux de naissance, et en particulier, le nombre de couples avec trois enfants est en hausse. At last we are off, exiting Hanoi by way of a major artery in the direction of the Haiphong Expressway.

I began, while he watched me intently like a prize pupil, by explaining the situation in the north, in Tonkin. Urban imagery still prevailing: “Samsung,” “Esso, “Computer Games.” Where the French in those days were hanging on to the delta of the Red River, which contained Hanoi and the only northern port, Haiphong (Graham Greene, The Quiet American). But giving way to narrow three-story suburban houses in lime, cream, citron and maroon, in mauve, grey and ocher. En 2004 la ville devrait compter 50.000 nouveau-nés dont 2.500 seront le troisième enfant. Here most of the rice was grown. Soit une augmentation de 0,38 %. And when it was ready the battle began.

Four blue-suited workmen in yellow hard hats stand together in a green field to inspect a tall pole strung with electric lines. Narrow gauge train tracks have begun to parallel our course. Banana trees, planted beneath the railway embankment are leafing out at track level. We pass a commercial lot filled with backhoes in orange, blue, white and yellow. Tel était le bilan présenté lors de la réunion, organisée à Hanoi par le Comité de la population, de la famille et des enfants à l’occasion de la Journée de la population du Vietnam, le 26 décembre. Roadside buildings are growing sparser, vegetable patches are turning into fields, factories are being constructed. A sign for LG Electronics Vietnam reads “Life’s Good!”

“That’s the north,” I said. Having napped through our passage across the most rural portions of the landscape, author awakens to witness the route’s reurbanization, which recommences after a rest stop. “The French may hold, poor devils, if the Chinese don’t come to help the Vietminh.” (We have paused in a courtyard filled with many other buses, scruffy European tourists cutting in line to buy coffee, to stock up on souvenirs.) “A war of jungle and mountain and marsh.” Back on the road pre-construction is taking place in the countryside: asphalt factory, cement production, the fabrication of bricks. “Paddy fields where you wade shoulder-high, and the enemy simply disappears.” Stacked beside huts.

“But you can rot in the damp of Hanoi.” Gradually the frequency of roadside houses increases, these new residences interspersed among flat fields of vegetables, brown clods being broken up for planting, paddies already irrigated. “They don’t throw bombs there.” Bicycles cross the four-lane expressway to get from one side to the other in villages divided in half by the otherwise inaccessible expressway. “God knows why.” A train heading for Hanoi approaches and passes. “You could call it a regular war.” Its boxcars in unpredictable colors. “And here in the South?” he asked. Its engine in red, white and blue, as we in turn pass a road marker reading “Haiphong / 22 km.”

“The French control the main roads until seven in the evening,” I replied. Au niveau national, le taux de croissance démographique enregistre cette année, une hausse visible. Villages are becoming more frequent. En 2003 de 1,47 %, soit 0,15 % de plus que par rapport à 2002. “Welcome to Hai Phong,” says a large blue billboard, though we are still “18 km” from the city, another marker reports. “After sunset they maintain control of the watch towers.” We pass a huge corrugated building with letters proclaiming it a “Joint Venture Steel Plant.” “Along with the towns—or parts of them.” “Hoguam Fabric Manufacturing,” “Nomura-Haiphong Industrial Zone,” “Taiwan Taifong Paper Company.”

“This doesn’t mean you’re safe.” At the outskirts of Hai Phong the expressway ends. We turn north onto a two-lane road, heading toward Ha Long City. Internet cafés, tea stalls, motorbike repair shops, beauty parlors line the way. Schools begin to appear. Then suddenly all gives way once more to open fields, many occupied with already-walled-in construction sites, others being bulldozed flat. Isolated new houses have been freshly painted cream and chocolate; green, blue and turquoise; rouge, rust and yellow. “Otherwise there wouldn’t be iron grilles in front of the restaurants.” We mount a high bridge for an overview of a landscape of water buffalo, women in conical hats, rice paddies, a cemetery.

Ce phénomène résulte de causes naturelles. Quickly we traverse several villages. In the marketplace of one, women wearing dark blue jackets and black pants huddle to converse, their wide straw hats almost touching one another. As we returned the sun had begun to decline. Before long the scene fills with tiny mountains, arranged as if for a class in oriental landscape painting, the various geological types all represented: The geographer’s moment had passed. Flat-topped hills; high spires; rises with undulant valleys; craggy outcrops. The Black River was no longer black. A long, continuous range in the distance. The Red River, only gold. An interrupted string of mountains, some of them precipitously shorn off.

Down we went again, away from the gnarled and fissured forest toward the river, flattening out over the neglected rice fields, aimed like a bullet at one small sampan on the yellow stream. At all their rocky feet lie paddies, some smoke-filled, as farmers clear and burn debris. The cannon gave a single burst of tracer. A woman in a white smock and a red woolen cap is breaking up clods with a hoe. The sampan blew apart in a shower of sparks. Behind her rises a miniature mountain like a rocky loaf of bread in a painting by the Yuan literatus Chao Meng-fu. We didn’t even wait to see our victims struggling to survive, but climbed and made for home. Some of the mountains are being quarried.

Ces femmes sont nées pour l’essentiel après les années de la guerre. We pass a fourteen-year-old boy on a bicycle, a pig strapped on behind its seat, slaughtered, singed and cut open. I thought again as I had thought when I saw the dead child at Phat Diem, “I hate war.” As we swerve across the centerline to pass them—pig and boy—an oncoming orange truck flashes its lights at us. There’d been something so shocking in our sudden fortuitous choice of a prey—we’d just happened to be passing, only one burst was required. A woman in a red hat and black leather jacket crosses the road on her bike. There was no one to return our fire. Turns and heads in the same direction that we are headed.

Museum of The Vietnamese Revolution, Hanoi, late afternoon visit. In his 1949 “Existentialisme et matérialisme dialectique” Tran Duc Thao advocates a concrete philosophy in opposition to the prevalent existentialist philosophy of his time. Having purchased our tickets from a very beautiful woman. Abstraction, according to Tran, dominates existentialist philosophy, because it adheres to phenomenological theory. We mount black steps to the second floor, where the exhibition, or so a sign tells us, begins. The epoché, or cornerstone, of Husserl’s philosophy. According to an attendant’s instructions we continue down a broad, cream-tiled corridor bordered with black baseboards.

Allows Husserl to posit a transcendental ego “outside the world.” Author takes seat opposite a black painting in four panels as a black-jacketed youth ambles past. While Heidegger, in turn, progresses beyond Husserl by recognizing that the latter’s transcendental ego is “a concrete and temporal self.” In the black painting a pagoda is depicted surrounded by trees of different species. According to Tran, he accomplishes this by recognizing that being-in-the-world must be analyzed in terms of “human reality.” Two red fire extinguishers stand on the floor at ready, their pincer-like handles facing in opposite directions. For Tran Duc Thao, however, Heidegger does not go far enough.

The black-jacketed youth returns only to exit at the end of the corridor through a glass door marked with a wide green horizontal stripe. Although identified with human reality, Heidegger’s being-in-the-world is still subjective. The museum is sparsely attended. Rather than a world that would ground the real human subject, Dasein merely grounds the world. Of the two electric “lanterns” above the black picture only one is illuminated. It is the subjectivism of phenomenology that causes existentialism to conceive of human existence as “a nothingness.” The black-jacketed youth, clearly an attendant himself, returns, attempting as he ducks past a second time to grasp the nature of author’s activity.

By contrast however, with explicit phenomenological doctrine. The first exhibition room represents “The Vietnamese People’s Resistance War against the French Invasion in the Second Half of the 19th Century.” Phenomenological practice, according to Tran Duc Thao, can provide results that improve upon subjectivism. It is filled with rather predicable black-and-white photos, along with almost random pieces of military armament: If pursued, such analyses, more faithful to phenomenology than to its theory. Sabre, rifle, cannon, etc. Would show that every human life, “my life,” as Tran Duc Thao says. A black map of Vietnam, Laos and Kampuchea. Was conditioned by “a certain milieu.”

It has had the names of its towns inlaid with mother-of-pearl. By certain social structures. Many animals in mother-of-pearl cover the country from North to South. By a certain material organization. Sailing vessels stand off the coast in mother-of-pearl. And that “my life” becomes meaningful only under these conditions. In a case hangs the black shirt “worn by Doan Hung, a miner at Hon Gai Colliery (Quang Ninh) during the time of the French Domination.” That I must protect such conditions if I want my life to retain this meaning. In the second room are exhibited more b/w photos, plus “the gun barrel used by Hoang Dinh Kinh (of Tay ethnic people) to fight the French in Lang Son, 1914.”

These conditions are not of my choosing. In another case are displayed a black scimitar and a black trident. The arbitrariness of subjective decisions does not account for them. Both weapons were employed against the French. Thus they are “objective,” but not in the sense of a world of ideas existing “in-itself.” Hanging on the wall is an umbrella that belonged to “one of the leaders of the National Party.” Rather, these structures belong to this world. It has no cloth. What, according to Tran Duc Thao, one must therefore investigate is “a material world.” Instead, only the metal stanchion that once supported it. As Tran says, “material being envelops the signification of life, as life in this world.”

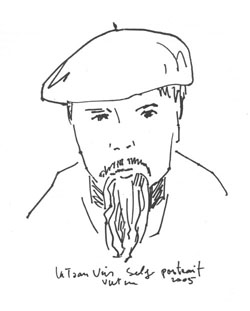

The third room documents “The Founding of The Vietnamese Communist Party (1930).” The moment of materiality constitutes the infrastructure of human life as the last foundation of every properly human meaning. It includes a wooden map of the world, onto which the continents, cut out of plywood, have been glued, their major cities lit by tiny bulbs, so as to indicate “the countries where President Ho Chi Minh sojourned from 1911-1941.” For Tran Duc Thao only dialectical materialism is capable of analyzing these real infrastructures. In a well-known Soviet Realist scene V.I. Lenin, wearing his trademark goatee, gesticulates toward a rowdy crowd as he directs the October Revolution.

One exhibition room attracts attention because of its video display. Carrying out what was only programmatically described in “Existentialisme et matérialisme dialectique.” Stepping inside to observe its contents. Phénoménologie et matérialisme dialectique presents a reading of Husserl’s then-known works, both published and unpublished. Author discovers that the “video display” is merely an ordinary television set. For Tran everything turns on Husserl’s Third Investigation. Tuned to a current soap opera. The concept of the foundation in Husserl is not a matter of deriving the intelligible from the sensible, since it is of the essence of “founded” acts to “intend” radically new objects.

“Vietnamese rifles used at Dien Bien Phu” have been lined up vertically in a case by themselves.” Nevertheless, the Third Investigation, taken in conjunction with Husserl’s Sixth Investigation’s notion of “categorical intuition.” Nguyen Tin’s bicycle (“used to transport food to the battle at Dien Bien Phu, 1954”). Shows how it is impossible to separate essences entirely from sensuous kernels. Is displayed as a freestanding exhibit, the bicycle supported by its own kickstand. On the basis of this inseparability. Its seat is black, but its struts and wheels have been repainted a dark green. Tran Duc Thao isolates three “ambiguities” in Husserl’s phenomenological theory.